12/05/2021 by Omar Mohammed

For centuries, the Old Suqs played a crucial role in developing and preserving a socio-economic system that facilitated coexistence in Mosul. They not only served as the economic core of the city, but they also brought the different groups of Mosul society together in a complex but solid social structure

The Old Suqs (Bazaars) of Mosul, the heart of the city’s social identity, were severely damaged during the battle to retake the city from ISIS. For centuries, the Old Suqs played a crucial role in developing and preserving a socio-economic system that facilitated coexistence in Mosul. They not only served as the economic core of the city, but they also brought the different groups of Mosul society together in a complex but solid social structure. In the markets, throughout the history of Mosul, Jewish, Christian and Muslim communities lived together and contributed to shaping Mosul’s identity. This was also the area where the Mosuli dialect, oral literature and proverbs were created.[1] A brief look at the collection of Mosul’s proverbs reveals thousands of proverbs related to the markets.

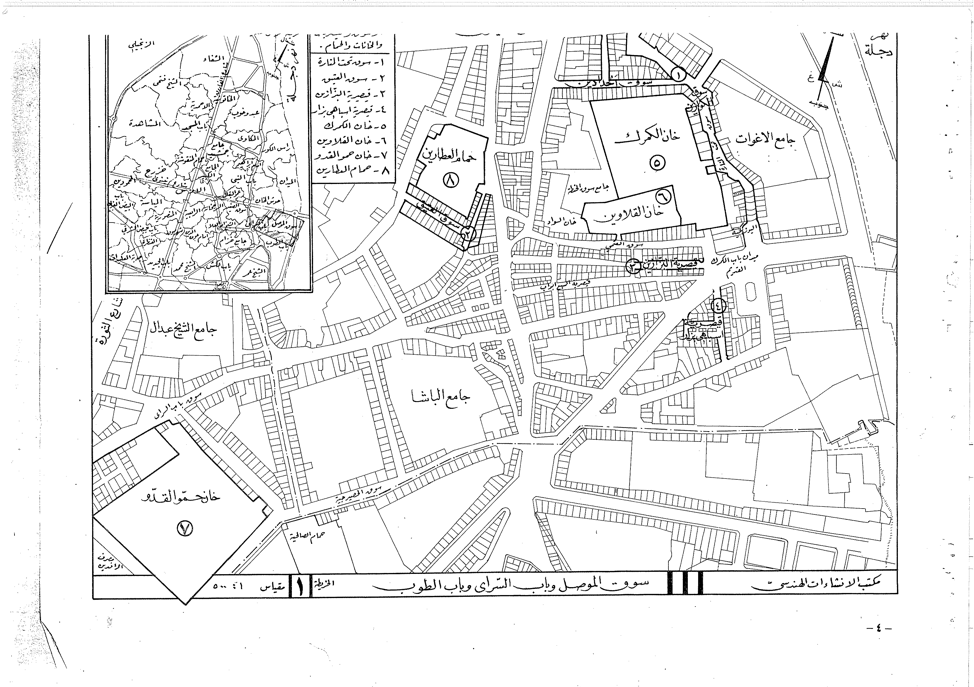

The Old Suqs are located in the south-east quarter of the city, where most of the cultural heritage sites are found, having developed around the medieval markets. The markets’ expansion was not just a sign of economic growth in Mosul. They also played a significant role in the politics of the ruling elites. The vast majority of markets in the Old City were built near a mosque or religious building or a historical site.[2] This explains the role mosques played in enhancing the cultural and economic life. Under the Atabegs, the market area grew considerably and spread north as well as south. After the fall of Mosul to the Mongols in 1262,[3] and throughout the Turkmen era, economic activity was significantly reduced, and the market area shrank to a small enclave. Such a decline in the market area not only harmed the economy, but also had a significant impact on the cultural life of the city. After the Ottomans occupied Mosul in 1519, the economy of the city once again began to flourish, a trend which continued during the Jalili era (1726-1834); the markets then gradually declined after the Ottoman centralization and later during the British Mandate, and after Iraq’s independence during the rules of Abd al-Karim Qasim and Saddam Hussein. When ISIS occupied Mosul in June 2014, they effected systematic changes and destroyed the Old Suqs, altering their historical identity and casting a shadow over the visual memory of the people.

Mosul’s markets had been established and divided by profession. Each market was named after the primary profession practised there. Some markets also took their names from the historical sites that make up the heart of the suq, such as Suq Al Nuri, which refers to the Al-Nuri Mosque. Other markets were connected to waqfiyyat (endowments) or kuttabs (elementary schools), or to a particular family that owned the land. The rise and growth of Mosul’s old markets contributed to a complex identity of the city and its people. Around the markets were the centres of the successive governments of the city. They also served as the political heart where the old and notable families of the city resided. This is also where the oldest churches of the various Christian sects were found, as well as important Islamic cultural heritage. It is safe to say that the markets of Old Mosul were at the heart of the city’s unique coexistence and diversity. However, this diversity was dependent on economic collaboration, which was based on the presence of each group’s historical sites. All were merged in the markets to serve their cultural and economic interests.

The social dynamics of Mosul can also be identified in the Old Suqs. The markets specialized in producing goods for the middle and upper classes, traders and workers. This diversity constituted a social structure that clearly illustrates how the people of Mosul were associated with their professions. The Great Nuri Mosque is the quarter where the oldest Christian families surrounded the heart of this geographical area, along with government buildings, the Central Bank and the public service administration.

In 2014, when ISIS tried to force the people to reopen their shops in the old markets, the people refused and resisted the order, as they realized that keeping the markets running would legitimize ISIS and its rule

It became a tradition in Mosul for a family to own a small shop in the old markets. Most of the notable families owned – through the endowment system – the old markets; other families and individuals aimed at buying property there in order to identify themselves with the city. This social process of buying property in the Old City played a significant role in the formation of Mosul’s social fabric. When the city was destroyed, many families began calculating their losses, not in the outskirts of the city nor the residential areas, but only in the old markets. This process of claiming historical authority is now playing a vital role in the reshaping of the city’s identity.

The markets were a locus of economic exchange. They were part of the social and historical dynamic that, besides what was discussed previously, shaped the local perspective on the regional and international culture and heritage. The market in Old Mosul used to welcome merchants from other countries as well as from other Iraqi cities. It helped to protect the city’s civic and historical identity by its impact on literature, language and history, through interaction between people of different ethnicities and cultures. It also had a significant influence on the architecture of Mosul.

In 2014, when ISIS tried to force the people to reopen their shops in the old markets, the people refused and resisted the order, as they realized that keeping the markets running would legitimize ISIS and its rule.[4] This act illustrates how people viewed their heritage and its importance. As a result, most of the local merchants and owners fled the city, in the hope of returning once ISIS was defeated. After the city was liberated in 2017, the merchants went back and found that almost everything that they had owned had been destroyed by the international coalition. They again had to emigrate, either to Kurdistan or to the East Bank of Mosul.

Below is a list of the most important destroyed markets in Old Mosul.

- Suq Bab-i Tub (Cannon Gate): This Ottoman suq occupies most of the central area surrounded by the Ottoman administrative buildings. It was the site of most of the traditional markets for middle-class people and also sold second-hand products. ISIS changed the architecture of the suq, destroying and replacing most of its ancient buildings. Moreover, they replaced the suq’s main mosque, Al-Sabunji, with a new mosque that they built and named after the former ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The market was heavily damaged during the battle to retake the city from ISIS.[5]

- Suq Haraj: The word haraj refers to the nature of the market itself, where lower- and middle-class city-dwellers go to shop, and where people come from rural areas to buy or sell products. The market is known for its disorganized crowds and shops. However, it is surrounded by very old Ottoman khans, hammams (bath houses) and markets. It is on the south side of the Bab-i Tub market. ISIS razed the old market to the ground and replaced it with a new market. Consequently, the Suq Haraj has lost its historical value. Part of it was also damaged during the battle to retake Mosul from ISIS. The importance of this market lies in the interconnections among the people around a historical space.

- Suq Al-Sawwafa (Wool Merchants’ Market): This market is located at the heart of the Old Suqs. It gave its name to one of the city’s notable families, which built its legacy on the wool trade with Britain and India, as well as the religious statue that the Sawwaf family obtained after Muhammed Mahmud Al Sawwaf returned from Egypt in the 1940s and established the second branch of the Muslim Brotherhood in Mosul. The legacy of these markets maintains the critical connection between the market growth in Mosul and the Jalili family’s leadership, when other families began competing for political influence. It also contributed to the development of Mosul’s cosmopolitan identity through trade between Mosul and other nations. The people neglected the market after ISIS occupied the city and harmed its cultural life, as many of the livestock owners stopped selling their goods to the city after ISIS seized their sheep and other animals. Rural and urban communities traditionally had found a space for communication in these markets, but once ISIS severed this connection, the market lost its value. It was completely destroyed during the battle to retake the city from ISIS. The Sawwaf family has now moved to Turkey.

- Suq Al-Attarin (Spice Market): This market is an important part of Mosul’s cultural heritage and is fundamentally connected to the beginning of Mosul’s development. It is located at the heart of Mosul’s Old City, the historic home of the wealthiest families, and is primarily owned by the most influential families, notably the Jalili family. It played a crucial role in placing Mosul on the Silk Road for its trade in spices with China and India. Furthermore, it still holds most of the Jalili family’s waqfiyyat. One indication of the market’s importance for the wealthy and powerful families of Mosul is that it is located right next to the goldsmiths’ market (Suq al-Sagha), where the city’s money was minted and held.

The concept of coexistence between different religions and ethnicities did not apply to Mosul’s neighbourhoods. The urban structure of neighbourhoods in Old Mosul is based on systematic social division. There are separate neighbourhoods for Christians, Muslims and Jews. Nevertheless, the real diversity, inclusion and coexistence took place in the city’s Old Suqs, as we can see multi-ethnic and multi-cultural groups working together in the same place in the Sagha market. This was the real value of both the space and the cultural heritage of the suq. Most of the owners and workers in these markets fled after ISIS occupied the city. ISIS also changed the market’s architecture and opened within the small alleys new ones that undermined the suq’s historical structure. This market also contained what was most important, both religiously and politically: the mosque of the Jalili family, Al-Pasha Mosque, named after Husayn Pasha al-Jalili, the second founder of the Jalili family and the Mosuli ruler who defeated Nadir Shah of Persia when he besieged Mosul in 1743. His legacy became a symbol of the cultural and political identity of Mosul. The mosque was heavily damaged during the battle to retake the city from ISIS. However, shortly after its liberation, the Jalili family and volunteers decided to rebuild the mosque. Its rehabilitation was completed in less than a year. They organized a ceremony to reopen the Al-Pasha Mosque, which is now functioning as a symbol of the resilience of the city and its people.

- Suq Al-Haddadin (Blacksmiths): Located east of Old Mosul, this compound comprises more than ninety shops dating back to the Ottoman era and mostly owned as awqaf (endowments) belonging to the Jalili family. It was the heart of the artisans’ area and was always crowded with farmers coming from the countryside to purchase farming tools. The market managed, for a long time, to maintain its Ottoman architecture. However, after 2014, ISIS remodelled most of the shops and did significant damage to the Ottoman style. It was destroyed during the battle to retake the city from ISIS. Volunteers have now partly renovated it with support from the Jalili family.

- Suq Al-Atamih (The Dark Market): This Ottoman market was known for its architectural design, which kept the market dark and protected. It was destroyed during the battle to retake Mosul from ISIS.

- Khan Al-Jumrik (Customs Khan): This market, owned and built by the Jalili family, was Mosul’s station on the Silk Road and served as its centre for international trade. Damaged during the battle to retake the city from ISIS, it has been renovated by the Jalili family as well.

- Bab-i Saray (The Palace Gate): Named after the old wall of Mosul, this is the Old City’s central market and contains Suq Al-Attarin, Al-Sagha, Al-Haddadin, Al-Najjarin and Al-Atamih. Much of it was damaged by ISIS and later during the battle to retake the city.

Source: Saad Hadi.

- Khan Hammu Al Kaddu: This is the only compound in Mosul built by the Al-Kaddu family with two levels in the middle of the eighteenth century, during the Ottoman era. The Khan contained more than 300 shops and rooms for merchants who came to Mosul from other areas and was used by Ottoman officials as a customs office. It was destroyed during the battle to retake Mosul from ISIS. Afterwards it was razed to the ground by the Kaddu family, who decided not to rebuild it. New buildings in a modern architectural style will replace it.

Although ISIS and the international coalition destroyed most of the markets mentioned above, local residents have restored several historic shops. The problem facing the city of Mosul and its cultural heritage is not how many shops can be restored to preserve its cultural identity. Rather, it is the reconstruction strategy, which has so far ignored both the social fabric and the complicated role of the market in providing a space where people can communicate. It has also ignored the importance of heritage preservation, as well as its impact on people’s visual memory. The international efforts to rebuild Mosul have, due to the planners’ lack of understanding of the Old City and its socio-economic fabric, accelerated the decline of this cultural heritage and its ability to protect the future of the city.

[1] On the proverbs of Mosul see Al-Dabbagh (1956: 21). See also Socin (1847).

[2] Akram Mohammed Al Hayaly, Mosul District during the Ottoman period according to the Architecture ruins (1516-1918). Thesis, Mosul University 2009.

[3] For more details see Qaddawi (2015).

[4] Please check the Mosul Eye website and the section dedicated to Heritage, https://mosul-eye.org/category/heritage.

[5] The list created by the author is based on documents he collected during his stay in Mosul under ISIS rule.

42 comments

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thank you very much for sharing, I learned a lot from your article. Very cool. Thanks.

Comments are closed.