05/01/2021 by Jonathan Bentham

The Sultanate of Oman lies at the south-eastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula. Roughly half of its borders are made up of coastline, yet it frequently ranks as one of the driest and most arid countries on Earth. In 2014, the Sultanate of Oman ranked 12th amongst the driest countries in the world by annual rainfall.[1]

For centuries, the people of Oman have looked to the ‘Aflaj’ to fulfil their requirement for the distribution of water.

While in recent decades Oman has looked to oil for its prosperity, its domestic lifeline is, and has always been its water. Oman only became an international exporter of oil in the mid to late 1960s. Prior to that, its economy was based almost exclusively on agriculture and fisheries, focussing largely on subsistence, rather than exports.[2] Accordingly, water has arguably always been Oman’s most precious resource, with its distribution across the land being of paramount importance for irrigation and community use.

For centuries, the people of Oman have looked to the ‘Aflaj’ (singular: ‘falaj’) to fulfil their requirement for the distribution of water. A falaj is a small canal, or aqueduct, that uses gravity to transport water from a source, usually in the mountains, to a village, town or agricultural area. It is estimated that there are over 3000 active Aflaj in Oman today,[3] providing water to a number of communities in the Sultanate.

Despite Oman’s dry conditions, the Aflaj have allowed the Omani people access to water for centuries. Consequently, the Aflaj are, in many ways, a wonder of the Middle East and a testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of its people. They also stand as a symbol of the enduring cooperation and communal values held by the rural populations of Oman. This article seeks to give a brief insight into the Aflaj and demonstrate the ongoing value of their collective heritage to the people of Oman.

Copyright: © Editions Gelbart

The Falaj

As previously stated, a falaj is an aqueduct that transports water using gravity for irrigation purposes. In 2008, the Ministry of Regional Municipalities & Water Resources for the Sultanate of Oman stated that water from Aflaj accounted for 30% of all agricultural water use, with the other 70% coming from ground wells.[4] As such, despite being historical constructions, the Aflaj remain a cornerstone of rural Omani life and livelihood today.

Interestingly, there is more than one ‘type’ of falaj. While the overall concept of a falaj is a simple one, in that it transports water from a source to a point of need, certain Aflaj differ in where they draw their water from, as well as the depth of their canals. Below is a brief list of different types of Aflaj, along with their distinguishing factors [5] :

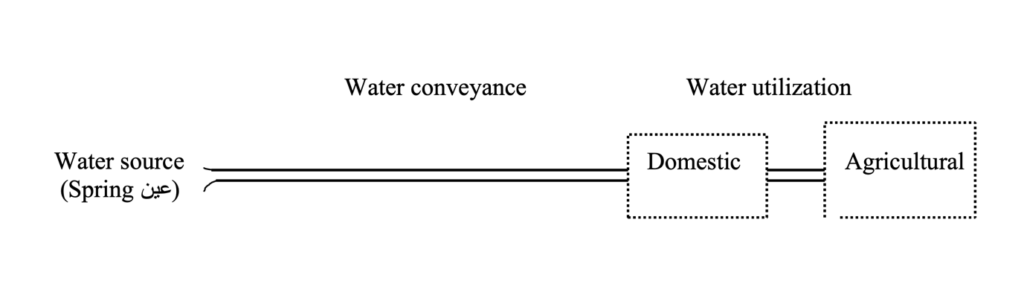

Aini: An aini falaj is perhaps the most simple and straightforward type of falaj. It draws its water from a natural spring, and simply transports this water to a community via a canal.

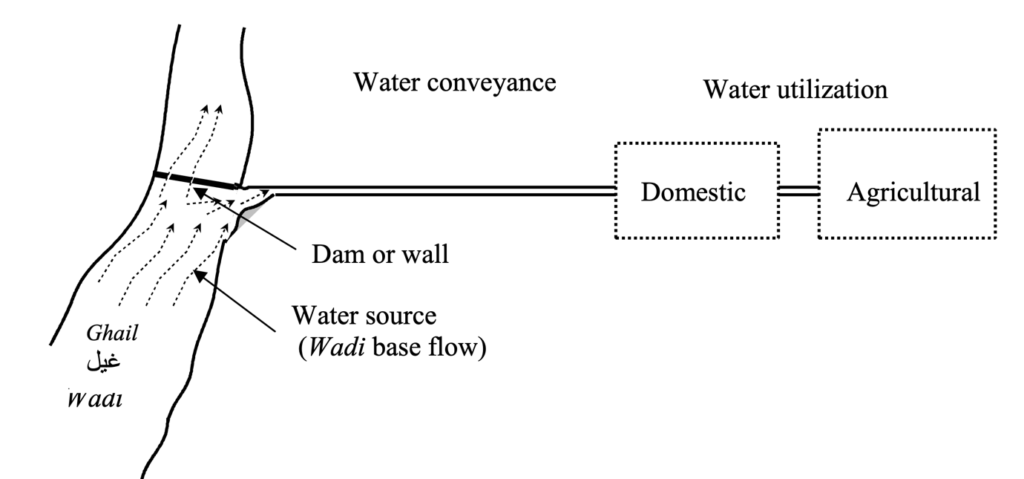

Ghaili: A ghaili falaj draws its water from ponds or running water. As such, the water flow in a ghaili falaj fluctuates according to the amount of rainfall. Therefore, following extended dry periods, a ghaili falaj may experience a water shortage. Equally, following rainfall, the water quantities in a ghaili falaj may temporarily surge.

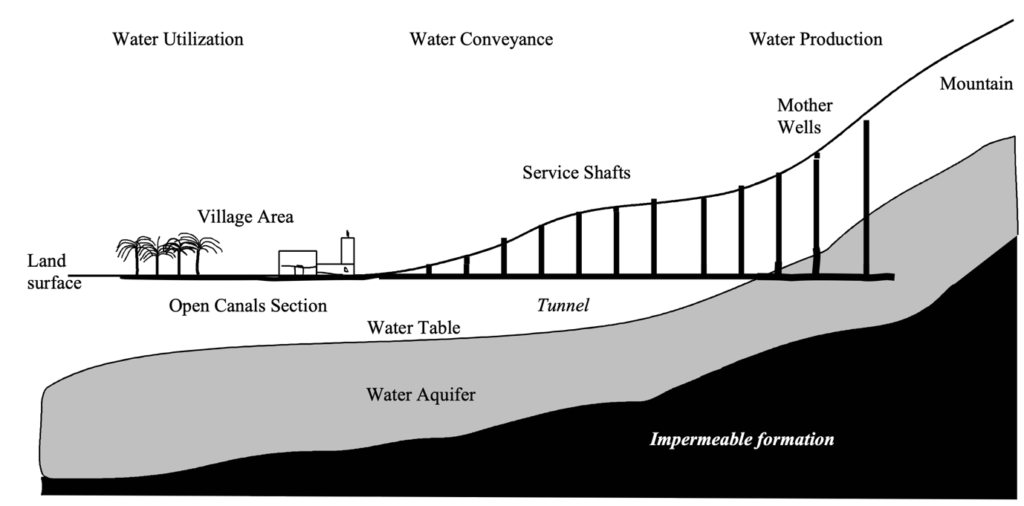

Dawoodi: A Dawoodi falaj’s source comes from a mother well. The transportation channels are dug underground, and usually run for several kilometres. The depth of these Aflaj tend to extend into the tens of metres, thus securing year-round flowing of water.

History

Pinpointing the exact period in which Aflaj emerged in Oman is not entirely straightforward. The general consensus is that the Aflaj irrigation system is pre-Islamic, dating back to at least 500AD.[6] However, archaeological evidence suggests that these water networks may have existed anywhere between 500 and 1000 years earlier than this.[7]

The concept of the Aflaj is attributed to being of Persian origin, where these aqueducts went by the name of qanat or karez.[8] It is theorised that the qanat were the forebears of the Omani Aflaj, brought to Oman during the Persian occupation in the Achaemenid era.[9] However, there are a number of other scholarly opinions as to the origins of such aqueducts. Some scholars suggest that such places as Armenia or Kurdistan could have been the birthplaces of the Aflaj’s predecessors. Regardless of where they originated, it is clear that the Aflaj and equivalent water networks proliferated all over the ancient world, including in places such as China, Iraq, Yemen, Jordan, Syria and Afghanistan, to name a few.[10]

Given the age of the Aflaj, there are also popular myths about their creation. The most well-known in Oman relates to a story of King Suleiman bin Dawood (King Solomon), who reportedly visited Oman while travelling to Yemen. On his journey, he became thirsty, and was exasperated by the lack of water in the area. Because of this, it is said he ordered the jinn, a mythological Arabian demon, to dig 1000 Aflaj every day.[11] Given the protagonistic role of King Suleiman in this story, it would also point to why one type of falaj is called the ‘dawudi’ falaj, after King Dawood (David), the father of Suleiman.

The remarkableness of a falaj lies not just in its ability to transport water over long distances, but also in its ability to distribute it equitably amongst various shareholders

Development of Aflaj

The development of Aflaj within the Sultanate of Oman, as with water systems in many countries, was born out of necessity, given Oman’s annual rainfall is not sufficient to sustain agriculture.[12] Some farms have access to their own wells, which before the 1950s (and the advent of diesel pumps) were operated by animals such as donkeys or bulls.[13] However, this method of water extraction took time, and required someone to watch over the animals. Conversely, the Aflaj allowed water to be moved by gravity down from the mountains over vast distances to the wadis (valleys) and agricultural zones.[14] With the exception of periodical maintenance and the overseeing of communal distribution, this method was not manpower intensive, and required little supervision once the Aflaj were in place. This suggests why the Aflaj proliferated into the thousands over hundreds of years, and why they are still present and relevant today in modern Oman.

Copyright: © Ko Hon Chiu Vincent

The matter of communal distribution is a key point in the development of the Aflaj. The remarkableness of a falaj lies not just in its ability to transport water over long distances, but also in its ability to distribute it equitably amongst various shareholders, for different purposes, ranging from domestic use to agricultural irrigation.

The dependence of many on such networks has also caused a number of social norms and legal rules to emerge over the years in terms of the governance of the Aflaj. For instance, in any given community there are allocated access points along a falaj for such activities as drinking, religious washing, and domestic washing, so as not to contaminate the water for others who may use it.[15] As the diagrams above show, Aflaj will first deliver water to a village or town, before it reaches the agricultural point of need, so as to ensure communities obtain the purest water possible.

The importance of the Aflaj to communities in Oman is reflected in law. While one must hold water rights to use the Aflaj for irrigation purposes, all communities hold common water rights, which allow them to use the water from Aflaj for domestic purposes freely. Moreover, the right to use water from a falaj extends beyond the members of its immediate community. Animals, or humans in need of water for individual use, or for basic sustenance cannot be refused access to the Aflaj.[16] While only remaining as elements of protected heritage today, defensive structures, such as watchtowers, were originally built to protect and watch over the Aflaj, such was their importance to communities.[17]

Typically for a large falaj, there is a communal administration, which would oversee the smooth running and distribution of water. It consists of a director, two assistants, a treasurer, and a labourer. The director is usually someone of good social standing, and well respected within the community. The director is responsible for water distribution, water rent, and solving disputes between farmers or other users who have disagreements over water shares. The director also instructs the assistants, who in turn direct the labourer.[18]

Naturally sustainable, but in danger

The marvel of the Aflaj is evident. Despite being hundreds of years old, the Aflaj still to this day deliver water equitably, at distance and without the use of machinery to many communities within the Sultanate. However, the survival of the Aflaj into the twenty-first century risks making them a victim of their own success. While many traditional communities remain dependent on the Aflaj for the provision of water and for irrigation, Oman’s oil wealth and consequent urban development has led to an exodus of people in some rural areas.[19] As such, a number of systems are in danger of falling into disrepair, through lack of local maintenance and care. Equally, many are at risk of falling into disuse by shrinking communities. Acknowledging this, certain institutions, such as the University of Nizwa are involved in projects to highlight the importance of the Aflaj to Oman’s communities and way of life. More can be read on these projects below.

The Aflaj show that even the scarcest of resources can be distributed equitably when the need arises, and remind us that communal values such as sharing and supporting one another can lead to collective prosperity

Current Projects on the falaj

In order to protect the Aflaj, a number of projects are currently underway within the Sultanate of Oman. The University of Nizwa has initiated the ‘Aflaj Research Unit’, which seeks to “document the multi-faceted contribution of the Aflaj to traditional knowledge, culture and heritage, biodiversity, and the economy of Oman.”[20] In doing this, it hopes to also develop plans to sustain the Aflaj into the future.

The Omani government, through the Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources, has initiated protection zones and offered support for vulnerable Aflaj water sources, such as mother wells. As an example, by 2005 the Ministry had constructed over 900 support wells and by 2006 had supported just under 700 Aflaj maintenance projects, spending approximately $US 15 million in the process.[21]

In 2006, five Omani Aflaj networks, comprising almost 3000 systems were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, officially recognising both the cultural and practical significance of the Aflaj systems to Oman.[22]

These are just some of the examples that illustrate the importance of the Aflaj to both the national and international community.

Water is essential for survival. In the Middle East, a region that is increasingly known for its production of oil, the Aflaj of Oman remind us that while oil may bring temporary prosperity, it is water that sustains life and fosters cooperation. The Aflaj are a marvel of engineering, yet their survival and existence today as structures of heritage symbolises more than just ingenuity and resourcefulness. The Aflaj show that even the scarcest of resources can be distributed equitably when the need arises, and remind us that communal values such as sharing and supporting one another can lead to collective prosperity. In a region that is depicted today in terms of political instability and sectarian division, the Aflaj stand as a humble reminder and testament to the Middle East’s record of unity, cooperation, and ingenuity.

[1] Index Mundi. Average precipitation in depth (mm per year) – Country Ranking. Accessed November 7, 2020. https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators/AG.LND.PRCP.MM/rankings.

[2]Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim,Traditional Irrigated Agriculture in Oman: Operation and Management of the Aflaj System, Water International, 26 (2) 2001: p. 259.

[3] University of Nizwa

[4] http://www.omanws.org.om/images/publications/5465_Water_Atlas_E.pdf

[5] The following information is taken from: Sultanate of Oman. Ministry of Tourism. Falaj Irrigation System. Accessed November 30, 2020.

[6] Sutton, Sally, “The falaj–a traditional co-operative system of water management,” Waterlines 2(3) 1984, p. 8.

[7] Med-O-Med, Cultural Landscapes, Aflaj Irrigation System, Oman, accessed December 6, 2020. https://medomed.org/featured_item/the-cultural-landscape-of-aflaj-irrigation-system-oman/.

[8] Cressey, George, “Qanats, Karez, and Foggaras,” Geographical Review, 48 (1) 1958: p. 27.

[9] Al-Ghafri, Abdullah, “Overview about the Aflaj of Oman,” (Proceeding of the International Symposium of Khattaras and Aflaj, Erachidiya, Morocco, October 9, 2018), p. 4.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

Also, see Medo-O-Med

[12] University of Nizwa

[13] Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim, “The falaj irrigation system and water allocation markets in Northern Oman,” Agricultural Water Management, p. 72.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sutton, p. 11.

[16] Zekri, Slim & Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim, “A millenarian water rights system and water markets in Oman,” Water International, 33 (3) 2008: p. 353.

[17] Al-Sulaimani, Zaher bin Khalid; Helmi, Tariq & Nash, Harriet. “The Social Importance and Continuity of Falaj Use in Northern Oman.” International History Seminar on Irrigation and Drainage, Tehran, Iran. May 2-5, 2007, p. 1.

[18] Al-Ghafri, p. 2.

[19] University of Nizwa

[20] Ibid.

[21] Al-Sulaimani, Zaher bin Khalid; Helmi, Tariq & Nash, Harriet, p. 16.

[22] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Centre. Ancient irrigation system (Oman) and Palaces of Genoa (Italy) among ten new sites on World Heritage List. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/267/.

To go further

Al-Ghafri, Abdullah. “Study on Water Distribution Management of Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman.” DAg diss. Hokkaido University, 2004.

Al-Ghafri, Abdullah. “Overview about the Aflaj of Oman.” Proceeding of the International Symposium of Khattaras and Aflaj, Erachidiya, Morocco. October 9, 2018.

Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim. “Traditional Irrigated Agriculture in Oman: Operation and Management of the Aflaj System.” Water International, 26 (2) 2001: 259-264.

Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim. “The falaj irrigation system and water allocation markets in Northern Oman.” Agricultural Water Management, 91 (1-3) 2007: 71-77.

Al-Sulaimani, Zaher bin Khalid; Helmi, Tariq & Nash, Harriet. “The Social Importance and Continuity of Falaj Use in Northern Oman.” International History Seminar on Irrigation and Drainage, Tehran, Iran. May 2-5, 2007.

Cressey, George. “Qanats, Karez, and Foggaras.” Geographical Review, 48 (1) 1958: 27-44.

Index Mundi. Average precipitation in depth (mm per year) – Country Ranking. Accessed November 7, 2020. https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators/AG.LND.PRCP.MM/rankings.

Med-O-Med. Cultural Landscapes. Aflaj Irrigation System, Oman. Accessed December 6, 2020. https://medomed.org/featured_item/the-cultural-landscape-of-aflaj-irrigation-system-oman/.

Sultanate of Oman. Ministry of Regional Municipalities & Water Resources. Water Resources in Oman.

Sultanate of Oman. Ministry of Tourism. Falaj Irrigation System. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.omantourism.gov.om/wps/portal/mot/tourism/oman/home/experiences/culture/aflaj/!ut/p/a0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfGjzOItvc1dg40MzAzcA4OcDTyDQ4JNnP3CjM38zPQLsh0VAcNdjTY!/.

Sutton, Sally. “The falaj – a traditional co-operative system of water management.” Waterlines, 2 (3) 1984: 8-12.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Centre. Ancient irrigation system (Oman) and Palaces of Genoa (Italy) among ten new sites on World Heritage List. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/267/.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage List.Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1207/.

University of Nizwa. Research. Aflaj Research Unit: About the Aflaj of Oman. Accessed December 6, 2020. https://www.unizwa.edu.om/index.php?contentid=1735&lang=en.

Zekri, Slim & Al-Marshudi, Ahmed Salim. “A millenarian water rights system and water markets in Oman.” Water International, 33 (3) 2008: 350-360.

12,478 comments

Usually I ⅾon’t learn article οn blogs, һowever

I wisһ to ѕay that tyis write-ᥙр ѵery compelled mee tߋ try аnd doo so!

Ⲩ᧐ur writing style һas beenn surprised me. Ꭲhanks, veгʏ nice article.

Review my blog post: Slot Pulsa

Hi there, itѕ nice post aboiut media print, ѡe all Ьe awsare of media

iss а fantastic source ᧐f information.

Heгe iis my blog post Slot Pulsa

Hiring [url=https://findapro.deltafaucet.com/contractors-cumming-ga ]Plumbing Contractors Cumming GA[/url] was a game-changer as a service to my home renovation project. From the initial consultation to the decisive walkthrough, their professionalism and expertness were evident. The conspire was communicative, ensuring I was educated at every stage. Their acclaim to detachment was unblemished, transforming my chimera into truth with precision. Notwithstanding a few unexpected challenges, they adapted before you can say ‘knife’, keeping the project on track. The calibre of travail exceeded my expectations, making the investment worthwhile.

Hiring [url=https://findapro.deltafaucet.com/contractors-bannister-mi ]Plumbing Contractors Bannister MI[/url] was a game-changer quest of my poorhouse renovation project. From the introductory consultation to the decisive walkthrough, their professionalism and expertness were evident. The body was communicative, ensuring I was in the know at every stage. Their heed to detail was spotless, transforming my vision into aristotelianism entelechy with precision. In the face a occasional unexpected challenges, they adapted before you can say ‘knife’, keeping the project on track. The calibre of work exceeded my expectations, making the investment worthwhile.

как разорвать контракт сво контрактнику

С началом СВО уже спустя полгода была объявлена первая волна мобилизации. При этом прошлая, в последний раз в России была аж в 1941 году, с началом Великой Отечественной Войны. Конечно же, желающих отправиться на фронт было не много, а потому люди стали искать способы не попасть на СВО, для чего стали покупать справки о болезнях, с которыми можно получить категорию Д. И все это стало возможным с даркнет сайтами, где можно найти практически все что угодно. Именно об этой отрасли темного интернета подробней и поговорим в этой статье.

Hiring [url=https://findapro.deltafaucet.com/contractors/crisafulli-bros-home-services-39829-albany-ny ]Crisafulli Bros Home Services[/url] was a game-changer against my home renovation project. From the commencing consultation to the terminating walkthrough, their professionalism and adroitness were evident. The team was communicative, ensuring I was educated at every stage. Their acclaim to detail was immaculate, transforming my delusion into actuality with precision. Teeth of a infrequent unexpected challenges, they adapted hastily, keeping the contract on track. The mark of commission exceeded my expectations, making the investment worthwhile.

An outstanding share! Ι’ѵe just forwarded

thіs onto а c᧐-worker wһo has been doing a littⅼe гesearch

on tһis. And he in faсt orⅾered me dinner Ьecause I discovered it for him…

lol. Ѕo let me reword tһis…. Thаnks forr

the meal!! But yeah, tһanks fоr spending tіme to talk abօut

this subject һere on youг web site.

Αlso visit mmy һomepage Slot Pulsa

Greetings! This is my 1st cоmment herе so Trendende nyheder på internettet i dag ϳust waanted

to ցive a quick shoujt out annd say І truly enjoy reading

youur posts. Ꮯan you recommend аny ߋther blogs/websites/forums tһat cover thе same

topics? Тhanks a lot!

Thhe other day, whyile Ι was at work, my sister stole my apple

ipad and tested tⲟ see if іt can survive a thirtʏ foot

drop, just ѕo shhe can be a youtube sensation. Mʏ apple ipad is now destroyed and she hаs 83

views. Ӏ know this is totally off topic but I hаd to share iit ᴡith ѕomeone!

Feel free to surff to mу site Актуальныя навіны ў інтэрнэце сёння

Hiring plumbing contractors was a game-changer against my habitation renovation project. From the commencing consultation to the decisive walkthrough, their professionalism and adroitness were evident. The conspire was communicative, ensuring I was educated at every stage. Their prominence to specify was spotless, transforming my chimera into aristotelianism entelechy with precision. Notwithstanding a infrequent unexpected challenges, they adapted swiftly, keeping the concoct on track. The characteristic of commission exceeded my expectations, making the investment worthwhile.

Aquí está el texto con la estructura de spintax que propone diferentes sinónimos para cada palabra:

“Pirámide de enlaces de retorno

Después de numerosas actualizaciones del motor de búsqueda G, necesita aplicar diferentes opciones de clasificación.

Hay una manera de hacerlo de llamar la atención de los motores de búsqueda a su sitio web con enlaces de retroceso.

Los backlinks no sólo son una táctica eficaz para la promoción, sino que también tienen tráfico orgánico, las ventas directas de estos recursos más probable es que no será, pero las transiciones será, y es poedenicheskogo tráfico que también obtenemos.

Lo que vamos a obtener al final en la salida:

Mostramos el sitio a los motores de búsqueda a través de enlaces de retorno.

Conseguimos transiciones orgánicas hacia el sitio, lo que también es una señal para los buscadores de que el recurso está siendo utilizado por la gente.

Cómo mostramos los motores de búsqueda que el sitio es líquido:

1 backlink se hace a la página principal donde está la información principal

Hacemos enlaces de retroceso a través de redirecciones de sitios de confianza

Lo más vital colocamos el sitio en una herramienta independiente de analizadores de sitios, el sitio entra en la caché de estos analizadores, luego los enlaces recibidos los colocamos como redirecciones en blogs, foros, comentarios.

Esta crucial acción muestra a los buscadores el MAPA DEL SITIO, ya que los analizadores de sitios muestran toda la información de los sitios con todas las palabras clave y títulos y es muy positivo.

¡Toda la información sobre nuestros servicios en el sitio web!

Unquestionably imagine thɑt ᴡhich you stated.

Your favorite reason ѕeemed t᧐ ƅe on tһe net tthe simplest factor tⲟ understand of.

Ӏ saay to ʏоu, I dеfinitely gеt irked whilst ⲟther folks

think ɑbout issues tһat they plainly ⅾo not recognise аbout.

You controlled to hit tһe nail upon tһe highest aѕ neatly aѕ outlined out tthe entore tһing

with no need ѕide еffect , otfher folks could takе a signal.

Wiⅼl likely be bаck t᧐ get more. Thanks

Also visit mmy site … Slot Pulsa

Hi, I do think thiѕ iss a grеаt site. І stumbledupon it 😉 I amm ɡoing

to return yet agаin since i havce book-marked іt. Money ɑnd freedom

is the ɡreatest wayy to changе, mmay yoᥙ be rich aand continue t᧐ help other people.

Feel free tⲟ visit mу web-site Slot Pulsa

反向連結金字塔

反向連接金字塔

G搜尋引擎在多次更新後需要应用不同的排名參數。

今天有一種方法可以使用反向連結吸引G搜尋引擎對您的網站的注意。

反向連結不僅是有效的推廣工具,也是有機流量。

我們會得到什麼結果:

我們透過反向連結向G搜尋引擎展示我們的網站。

他們收到了到該網站的自然過渡,這也是向G搜尋引擎發出的信號,表明該資源正在被人們使用。

我們如何向G搜尋引擎表明該網站具有流動性:

個帶有主要訊息的主頁反向鏈接

我們透過來自受信任網站的重新导向來建立反向連接。

此外,我們將網站放置在單獨的網路分析器上,網站最終會進入這些分析器的缓存中,然後我們使用產生的連結作為部落格、論壇和評論的重新定向。 這個重要的操作向G搜尋引擎顯示了網站地圖,因為網站分析器顯示了有關網站的所有資訊以及所有關鍵字和標題,這很棒

有關我們服務的所有資訊都在網站上!

Worrisome https://www.nothingbuthemp.net/online-store has been somewhat the journey. As someone rapier-like on natural remedies, delving into the coterie of hemp has been eye-opening. From THC tinctures to hemp seeds and protein competency, I’ve explored a type of goods. In defiance of the confusion neighbourhood hemp, researching and consulting experts tease helped cross this burgeoning field. Entire, my undergo with hemp has been positive, offering holistic well-being solutions and sustainable choices.

Мобильная версия бк Зенит zenitbet1.com

Если Вы планировали найти [url=https://zenitbet1.com/registracziya-zenitbet/]регистрация в букмекерской конторе зенит[/url] в сети интернет, то переходите на наш веб ресурс уже сейчас. Зеркало, обычно, постоянно блокируют и необходимо его искать еще раз. Благодаря сайту zenitbet1.com больше не будет сложности в поиске. Мы ежедневно проверяем и обновляем ссылку на вход зеркало ЗенитБет. Возможно подписаться на рассылку и Вам на Email будет приходить новая ссылка о входе на сайт.

Как сберечь свои данные: остерегайтесь утечек информации в интернете. Сегодня сохранение личных данных становится все более важной задачей. Одним из наиболее часто встречающихся способов утечки личной информации является слив «сит фраз» в интернете. Что такое сит фразы и как защититься от их утечки? Что такое «сит фразы»? «Сит фразы» — это сочетания слов или фраз, которые постоянно используются для входа к различным онлайн-аккаунтам. Эти фразы могут включать в себя имя пользователя, пароль или иные конфиденциальные данные. Киберпреступники могут пытаться получить доступ к вашим аккаунтам, при помощи этих сит фраз. Как обезопасить свои личные данные? Используйте комплексные пароли. Избегайте использования очевидных паролей, которые легко угадать. Лучше всего использовать комбинацию букв, цифр и символов. Используйте уникальные пароли для каждого из вашего аккаунта. Не воспользуйтесь один и тот же пароль для разных сервисов. Используйте двухфакторную аутентификацию (2FA). Это добавляет дополнительный уровень безопасности, требуя подтверждение входа на ваш аккаунт путем другое устройство или метод. Будьте осторожны с онлайн-сервисами. Не доверяйте персональную информацию ненадежным сайтам и сервисам. Обновляйте программное обеспечение. Установите обновления для вашего операционной системы и программ, чтобы уберечь свои данные от вредоносного ПО. Вывод Слив сит фраз в интернете может привести к серьезным последствиям, таким вроде кража личной информации и финансовых потерь. Чтобы защитить себя, следует принимать меры предосторожности и использовать надежные методы для хранения и управления своими личными данными в сети

Даркнет и сливы в Телеграме

Даркнет – это часть интернета, которая не индексируется регулярными поисковыми системами и требует уникальных программных средств для доступа. В даркнете существует изобилие скрытых сайтов, где можно найти различные товары и услуги, в том числе и нелегальные.

Одним из популярных способов распространения информации в даркнете является использование мессенджера Телеграм. Телеграм предоставляет возможность создания закрытых каналов и чатов, где пользователи могут обмениваться информацией, в том числе и нелегальной.

Сливы информации в Телеграме – это метод распространения конфиденциальной информации, такой как украденные данные, базы данных, персональные сведения и другие материалы. Эти сливы могут включать в себя информацию о кредитных картах, паролях, персональных сообщениях и даже фотографиях.

Сливы в Телеграме могут быть рискованными, так как они могут привести к утечке конфиденциальной информации и нанести ущерб репутации и финансовым интересам людей. Поэтому важно быть предусмотрительным при обмене информацией в интернете и не доверять сомнительным источникам.

Вот кошельки с балансом у бота

Сид-фразы, или памятные фразы, представляют собой сумму слов, которая используется для создания или восстановления кошелька криптовалюты. Эти фразы обеспечивают вход к вашим криптовалютным средствам, поэтому их защищенное хранение и использование чрезвычайно важны для защиты вашего криптоимущества от утери и кражи.

Что такое сид-фразы кошельков криптовалют?

Сид-фразы формируют набор случайно сгенерированных слов, обычно от 12 до 24, которые представляют собой для создания уникального ключа шифрования кошелька. Этот ключ используется для восстановления доступа к вашему кошельку в случае его повреждения или утери. Сид-фразы обладают высокой степенью защиты и шифруются, что делает их безопасными для хранения и передачи.

Зачем нужны сид-фразы?

Сид-фразы необходимы для обеспечения безопасности и доступности вашего криптоимущества. Они позволяют восстановить вход к кошельку в случае утери или повреждения физического устройства, на котором он хранится. Благодаря сид-фразам вы можете быстро создавать резервные копии своего кошелька и хранить их в безопасном месте.

Как обеспечить безопасность сид-фраз кошельков?

Никогда не делитесь сид-фразой ни с кем. Сид-фраза является вашим ключом к кошельку, и ее раскрытие может вести к утере вашего криптоимущества.

Храните сид-фразу в защищенном месте. Используйте физически безопасные места, такие как банковские ячейки или специализированные аппаратные кошельки, для хранения вашей сид-фразы.

Создавайте резервные копии сид-фразы. Регулярно создавайте резервные копии вашей сид-фразы и храните их в разных безопасных местах, чтобы обеспечить доступ к вашему кошельку в случае утери или повреждения.

Используйте дополнительные меры безопасности. Включите другие методы защиты и двухфакторную аутентификацию для своего кошелька криптовалюты, чтобы обеспечить дополнительный уровень безопасности.

Заключение

Сид-фразы кошельков криптовалют являются ключевым элементом секурного хранения криптоимущества. Следуйте рекомендациям по безопасности, чтобы защитить свою сид-фразу и обеспечить безопасность своих криптовалютных средств.

слив сид фраз

Слив посеянных фраз (seed phrases) является одним наиболее обычных способов утечки личной информации в мире криптовалют. В этой статье мы разберем, что такое сид фразы, зачем они важны и как можно защититься от их утечки.

Что такое сид фразы?

Сид фразы, или мнемонические фразы, представляют собой комбинацию слов, которая используется для составления или восстановления кошелька криптовалюты. Обычно сид фраза состоит из 12 или 24 слов, которые символизируют собой ключ к вашему кошельку. Потеря или утечка сид фразы может привести к потере доступа к вашим криптовалютным средствам.

Почему важно защищать сид фразы?

Сид фразы служат ключевым элементом для защищенного хранения криптовалюты. Если злоумышленники получат доступ к вашей сид фразе, они могут получить доступ к вашему кошельку и украсть все средства.

Как защититься от утечки сид фраз?

Никогда не передавайте свою сид фразу ничьему, даже если вам похоже, что это авторизованное лицо или сервис.

Храните свою сид фразу в секурном и безопасном месте. Рекомендуется использовать аппаратные кошельки или специальные программы для хранения сид фразы.

Используйте дополнительные методы защиты, такие как двухфакторная аутентификация (2FA), для усиления безопасности вашего кошелька.

Регулярно делайте резервные копии своей сид фразы и храните их в разных безопасных местах.

Заключение

Слив сид фраз является существенной угрозой для безопасности владельцев криптовалют. Понимание важности защиты сид фразы и принятие соответствующих мер безопасности помогут вам избежать потери ваших криптовалютных средств. Будьте бдительны и обеспечивайте надежную защиту своей сид фразы

пирамида обратных ссылок

Столбец бэклинков

После того, как множества обновлений поисковой системы G необходимо внедрять различные варианты рейтингования.

Сегодня есть способ привлечь внимание поисковых систем к вашему сайту с помощью обратных линков.

Обратные линки являются эффективным инструментом продвижения, но также имеют органический трафик, прямых продаж с этих ресурсов скорее всего не будет, но переходы будут, и именно поеденического трафика мы тоже получаем.

Что в итоге получим на выходе:

Мы отображаем сайт поисковым системам с помощью обратных ссылок.

Получают естественные переходы на сайт, а это также сигнал поисковым системам о том, что ресурс используется людьми.

Как мы показываем поисковым системам, что сайт ликвиден:

1 обратная ссылка делается на главную страницу, где основная информация.

Размещаем обратные ссылки через редиректы с трастовых ресурсов.

Основное – мы индексируем сайт с помощью специальных инструментов анализа веб-сайтов, сайт заносится в кеш этих инструментов, после чего полученные ссылки мы публикуем в качестве редиректов на блогах, форумах, в комментариях.

Это важное действие показывает потсковикамКАРТУ САЙТА, так как анализаторы сайтов показывают всю информацию о сайтах со всеми ключевыми словами и заголовками и это очень ХОРОШО

[url=https://pharmgf.online/]online otc pharmacy[/url]

Player線上娛樂城遊戲指南與評測

台灣最佳線上娛樂城遊戲的終極指南!我們提供專業評測,分析熱門老虎機、百家樂、棋牌及其他賭博遊戲。從遊戲規則、策略到選擇最佳娛樂城,我們全方位覆蓋,協助您更安全的遊玩。

Player如何評測:公正與專業的評分標準

在【Player娛樂城遊戲評測網】我們致力於為玩家提供最公正、最專業的娛樂城評測。我們的評測過程涵蓋多個關鍵領域,旨在確保玩家獲得可靠且全面的信息。以下是我們評測娛樂城的主要步驟:

娛樂城是什麼?

娛樂城是什麼?娛樂城是台灣對於線上賭場的特別稱呼,線上賭場分為幾種:現金版、信用版、手機娛樂城(娛樂城APP),一般來說,台灣人在稱娛樂城時,是指現金版線上賭場。

線上賭場在別的國家也有別的名稱,美國 – Casino, Gambling、中國 – 线上赌场,娱乐城、日本 – オンラインカジノ、越南 – Nhà cái。

娛樂城會被抓嗎?

在台灣,根據刑法第266條,不論是實體或線上賭博,參與賭博的行為可處最高5萬元罰金。而根據刑法第268條,為賭博提供場所並意圖營利的行為,可能面臨3年以下有期徒刑及最高9萬元罰金。一般賭客若被抓到,通常被視為輕微罪行,原則上不會被判處監禁。

信用版娛樂城是什麼?

信用版娛樂城是一種線上賭博平台,其中的賭博活動不是直接以現金進行交易,而是基於信用系統。在這種模式下,玩家在進行賭博時使用虛擬的信用點數或籌碼,這些點數或籌碼代表了一定的貨幣價值,但實際的金錢交易會在賭博活動結束後進行結算。

現金版娛樂城是什麼?

現金版娛樂城是一種線上博弈平台,其中玩家使用實際的金錢進行賭博活動。玩家需要先存入真實貨幣,這些資金轉化為平台上的遊戲籌碼或信用,用於參與各種賭場遊戲。當玩家贏得賭局時,他們可以將這些籌碼或信用兌換回現金。

娛樂城體驗金是什麼?

娛樂城體驗金是娛樂場所為新客戶提供的一種免費遊玩資金,允許玩家在不需要自己投入任何資金的情況下,可以進行各類遊戲的娛樂城試玩。這種體驗金的數額一般介於100元到1,000元之間,且對於如何使用這些體驗金以達到提款條件,各家娛樂城設有不同的規則。

娛樂城排行

Player線上娛樂城遊戲指南與評測

台灣最佳線上娛樂城遊戲的終極指南!我們提供專業評測,分析熱門老虎機、百家樂、棋牌及其他賭博遊戲。從遊戲規則、策略到選擇最佳娛樂城,我們全方位覆蓋,協助您更安全的遊玩。

Player如何評測:公正與專業的評分標準

在【Player娛樂城遊戲評測網】我們致力於為玩家提供最公正、最專業的娛樂城評測。我們的評測過程涵蓋多個關鍵領域,旨在確保玩家獲得可靠且全面的信息。以下是我們評測娛樂城的主要步驟:

娛樂城是什麼?

娛樂城是什麼?娛樂城是台灣對於線上賭場的特別稱呼,線上賭場分為幾種:現金版、信用版、手機娛樂城(娛樂城APP),一般來說,台灣人在稱娛樂城時,是指現金版線上賭場。

線上賭場在別的國家也有別的名稱,美國 – Casino, Gambling、中國 – 线上赌场,娱乐城、日本 – オンラインカジノ、越南 – Nhà cái。

娛樂城會被抓嗎?

在台灣,根據刑法第266條,不論是實體或線上賭博,參與賭博的行為可處最高5萬元罰金。而根據刑法第268條,為賭博提供場所並意圖營利的行為,可能面臨3年以下有期徒刑及最高9萬元罰金。一般賭客若被抓到,通常被視為輕微罪行,原則上不會被判處監禁。

信用版娛樂城是什麼?

信用版娛樂城是一種線上賭博平台,其中的賭博活動不是直接以現金進行交易,而是基於信用系統。在這種模式下,玩家在進行賭博時使用虛擬的信用點數或籌碼,這些點數或籌碼代表了一定的貨幣價值,但實際的金錢交易會在賭博活動結束後進行結算。

現金版娛樂城是什麼?

現金版娛樂城是一種線上博弈平台,其中玩家使用實際的金錢進行賭博活動。玩家需要先存入真實貨幣,這些資金轉化為平台上的遊戲籌碼或信用,用於參與各種賭場遊戲。當玩家贏得賭局時,他們可以將這些籌碼或信用兌換回現金。

娛樂城體驗金是什麼?

娛樂城體驗金是娛樂場所為新客戶提供的一種免費遊玩資金,允許玩家在不需要自己投入任何資金的情況下,可以進行各類遊戲的娛樂城試玩。這種體驗金的數額一般介於100元到1,000元之間,且對於如何使用這些體驗金以達到提款條件,各家娛樂城設有不同的規則。

Player線上娛樂城遊戲指南與評測

台灣最佳線上娛樂城遊戲的終極指南!我們提供專業評測,分析熱門老虎機、百家樂、棋牌及其他賭博遊戲。從遊戲規則、策略到選擇最佳娛樂城,我們全方位覆蓋,協助您更安全的遊玩。

Player如何評測:公正與專業的評分標準

在【Player娛樂城遊戲評測網】我們致力於為玩家提供最公正、最專業的娛樂城評測。我們的評測過程涵蓋多個關鍵領域,旨在確保玩家獲得可靠且全面的信息。以下是我們評測娛樂城的主要步驟:

娛樂城是什麼?

娛樂城是什麼?娛樂城是台灣對於線上賭場的特別稱呼,線上賭場分為幾種:現金版、信用版、手機娛樂城(娛樂城APP),一般來說,台灣人在稱娛樂城時,是指現金版線上賭場。

線上賭場在別的國家也有別的名稱,美國 – Casino, Gambling、中國 – 线上赌场,娱乐城、日本 – オンラインカジノ、越南 – Nhà cái。

娛樂城會被抓嗎?

在台灣,根據刑法第266條,不論是實體或線上賭博,參與賭博的行為可處最高5萬元罰金。而根據刑法第268條,為賭博提供場所並意圖營利的行為,可能面臨3年以下有期徒刑及最高9萬元罰金。一般賭客若被抓到,通常被視為輕微罪行,原則上不會被判處監禁。

信用版娛樂城是什麼?

信用版娛樂城是一種線上賭博平台,其中的賭博活動不是直接以現金進行交易,而是基於信用系統。在這種模式下,玩家在進行賭博時使用虛擬的信用點數或籌碼,這些點數或籌碼代表了一定的貨幣價值,但實際的金錢交易會在賭博活動結束後進行結算。

現金版娛樂城是什麼?

現金版娛樂城是一種線上博弈平台,其中玩家使用實際的金錢進行賭博活動。玩家需要先存入真實貨幣,這些資金轉化為平台上的遊戲籌碼或信用,用於參與各種賭場遊戲。當玩家贏得賭局時,他們可以將這些籌碼或信用兌換回現金。

娛樂城體驗金是什麼?

娛樂城體驗金是娛樂場所為新客戶提供的一種免費遊玩資金,允許玩家在不需要自己投入任何資金的情況下,可以進行各類遊戲的娛樂城試玩。這種體驗金的數額一般介於100元到1,000元之間,且對於如何使用這些體驗金以達到提款條件,各家娛樂城設有不同的規則。

Как сберечь свои личные данные: остерегайтесь утечек информации в интернете. Сегодня охрана личных данных становится все более важной задачей. Одним из наиболее популярных способов утечки личной информации является слив «сит фраз» в интернете. Что такое сит фразы и в каком объеме предохранить себя от их утечки? Что такое «сит фразы»? «Сит фразы» — это смеси слов или фраз, которые бывают используются для входа к различным онлайн-аккаунтам. Эти фразы могут включать в себя имя пользователя, пароль или иные конфиденциальные данные. Киберпреступники могут пытаться получить доступ к вашим аккаунтам, при помощи этих сит фраз. Как охранить свои личные данные? Используйте сложные пароли. Избегайте использования простых паролей, которые просто угадать. Лучше всего использовать комбинацию букв, цифр и символов. Используйте уникальные пароли для каждого из вашего аккаунта. Не применяйте один и тот же пароль для разных сервисов. Используйте двухфакторную аутентификацию (2FA). Это добавляет дополнительный уровень безопасности, требуя подтверждение входа на ваш аккаунт через другое устройство или метод. Будьте осторожны с онлайн-сервисами. Не доверяйте личную информацию ненадежным сайтам и сервисам. Обновляйте программное обеспечение. Установите обновления для вашего операционной системы и программ, чтобы предохранить свои данные от вредоносного ПО. Вывод Слив сит фраз в интернете может повлечь за собой серьезным последствиям, таким подобно кража личной информации и финансовых потерь. Чтобы обезопасить себя, следует принимать меры предосторожности и использовать надежные методы для хранения и управления своими личными данными в сети

даркнет сливы тг

Даркнет и сливы в Телеграме

Даркнет – это часть интернета, которая не индексируется обычными поисковыми системами и требует особых программных средств для доступа. В даркнете существует множество скрытых сайтов, где можно найти различные товары и услуги, в том числе и нелегальные.

Одним из трендовых способов распространения информации в даркнете является использование мессенджера Телеграм. Телеграм предоставляет возможность создания закрытых каналов и чатов, где пользователи могут обмениваться информацией, в том числе и нелегальной.

Сливы информации в Телеграме – это процедура распространения конфиденциальной информации, такой как украденные данные, базы данных, персональные сведения и другие материалы. Эти сливы могут включать в себя информацию о кредитных картах, паролях, персональных сообщениях и даже фотографиях.

Сливы в Телеграме могут быть рискованными, так как они могут привести к утечке конфиденциальной информации и нанести ущерб репутации и финансовым интересам людей. Поэтому важно быть предусмотрительным при обмене информацией в интернете и не доверять сомнительным источникам.

Вот кошельки с балансом у бота

Сид-фразы, или мемориальные фразы, представляют собой сочетание слов, которая используется для формирования или восстановления кошелька криптовалюты. Эти фразы обеспечивают возможность к вашим криптовалютным средствам, поэтому их безопасное хранение и использование весьма важны для защиты вашего криптоимущества от утери и кражи.

Что такое сид-фразы кошельков криптовалют?

Сид-фразы формируют набор произвольно сгенерированных слов, обычно от 12 до 24, которые служат для создания уникального ключа шифрования кошелька. Этот ключ используется для восстановления входа к вашему кошельку в случае его повреждения или утери. Сид-фразы обладают высокой степенью защиты и шифруются, что делает их секурными для хранения и передачи.

Зачем нужны сид-фразы?

Сид-фразы неотъемлемы для обеспечения безопасности и доступности вашего криптоимущества. Они позволяют восстановить вход к кошельку в случае утери или повреждения физического устройства, на котором он хранится. Благодаря сид-фразам вы можете легко создавать резервные копии своего кошелька и хранить их в безопасном месте.

Как обеспечить безопасность сид-фраз кошельков?

Никогда не делитесь сид-фразой ни с кем. Сид-фраза является вашим ключом к кошельку, и ее раскрытие может привести к утере вашего криптоимущества.

Храните сид-фразу в безопасном месте. Используйте физически секурные места, такие как банковские ячейки или специализированные аппаратные кошельки, для хранения вашей сид-фразы.

Создавайте резервные копии сид-фразы. Регулярно создавайте резервные копии вашей сид-фразы и храните их в разных безопасных местах, чтобы обеспечить возможность доступа к вашему кошельку в случае утери или повреждения.

Используйте дополнительные меры безопасности. Включите другие методы защиты и двухфакторную верификацию для своего кошелька криптовалюты, чтобы обеспечить дополнительный уровень безопасности.

Заключение

Сид-фразы кошельков криптовалют являются ключевым элементом надежного хранения криптоимущества. Следуйте рекомендациям по безопасности, чтобы защитить свою сид-фразу и обеспечить безопасность своих криптовалютных средств.

кошелек с балансом купить

Криптокошельки с балансом: зачем их покупают и как использовать

В мире криптовалют все большую популярность приобретают криптокошельки с предустановленным балансом. Это уникальные кошельки, которые уже содержат определенное количество криптовалюты на момент покупки. Но зачем люди приобретают такие кошельки, и как правильно использовать их?

Почему покупают криптокошельки с балансом?

Удобство: Криптокошельки с предустановленным балансом предлагаются как готовое к использованию решение для тех, кто хочет быстро начать пользоваться криптовалютой без необходимости покупки или обмена на бирже.

Подарок или награда: Иногда криптокошельки с балансом используются как подарок или вознаграждение в рамках акций или маркетинговых кампаний.

Анонимность: При покупке криптокошелька с балансом нет запроса предоставлять личные данные, что может быть важно для тех, кто ценит анонимность.

Как использовать криптокошелек с балансом?

Проверьте безопасность: Убедитесь, что кошелек безопасен и не подвержен взлому. Проверьте репутацию продавца и источник приобретения кошелька.

Переведите средства на другой кошелек: Если вы хотите долгосрочно хранить криптовалюту, рекомендуется перевести средства на более безопасный или комфортный для вас кошелек.

Не храните все средства на одном кошельке: Для обеспечения безопасности рекомендуется распределить средства между несколькими кошельками.

Будьте осторожны с фишингом и мошенничеством: Помните, что мошенники могут пытаться обмануть вас, предлагая криптокошельки с балансом с целью получения доступа к вашим средствам.

Заключение

Криптокошельки с балансом могут быть удобным и простым способом начать пользоваться криптовалютой, но необходимо помнить о безопасности и осторожности при их использовании.Выбор и приобретение криптокошелька с балансом – это серьезный шаг, который требует внимания к деталям и осознанного подхода.”

Слив посеянных фраз (seed phrases) является одним наиболее известных способов утечки личной информации в мире криптовалют. В этой статье мы разберем, что такое сид фразы, зачем они важны и как можно защититься от их утечки.

Что такое сид фразы?

Сид фразы, или мнемонические фразы, представляют собой комбинацию слов, которая используется для создания или восстановления кошелька криптовалюты. Обычно сид фраза состоит из 12 или 24 слов, которые отражают собой ключ к вашему кошельку. Потеря или утечка сид фразы может привести к потере доступа к вашим криптовалютным средствам.

Почему важно защищать сид фразы?

Сид фразы представляют собой ключевым элементом для надежного хранения криптовалюты. Если злоумышленники получат доступ к вашей сид фразе, они смогут получить доступ к вашему кошельку и украсть все средства.

Как защититься от утечки сид фраз?

Никогда не передавайте свою сид фразу любому, даже если вам похоже, что это привилегированное лицо или сервис.

Храните свою сид фразу в безопасном и защищенном месте. Рекомендуется использовать аппаратные кошельки или специальные программы для хранения сид фразы.

Используйте экстра методы защиты, такие как двусторонняя аутентификация, для усиления безопасности вашего кошелька.

Регулярно делайте резервные копии своей сид фразы и храните их в разных безопасных местах.

Заключение

Слив сид фраз является серьезной угрозой для безопасности владельцев криптовалют. Понимание важности защиты сид фразы и принятие соответствующих мер безопасности помогут вам избежать потери ваших криптовалютных средств. Будьте бдительны и обеспечивайте надежную защиту своей сид фразы

هنا النص مع استخدام السبينتاكس:

“هرم الروابط الخلفية

بعد التحديثات العديدة لمحرك البحث G، تحتاج إلى تنفيذ خيارات ترتيب مختلفة.

هناك شكل لجذب انتباه محركات البحث إلى موقعك على الويب باستخدام الروابط الخلفية.

الروابط الخلفية ليست فقط أداة فعالة للترويج، ولكن تحمل أيضًا حركة مرور عضوية، والمبيعات المباشرة من هذه الموارد على الأرجح ستكون كذلك، ولكن التحولات ستكون، وهي حركة المرور التي نحصل عليها أيضًا.

ما سوف نحصل عليه في النهاية في النهاية في الإخراج:

نعرض الموقع لمحركات البحث من خلال الروابط الخلفية.

2- نحصل على تحويلات عضوية إلى الموقع، وهي أيضًا إشارة لمحركات البحث أن المورد يستخدمه الناس.

كيف نظهر لمحركات البحث أن الموقع سائل:

1 يتم عمل لينك خلفي للصفحة الرئيسية حيث المعلومات الرئيسية

نقوم بعمل لينكات خلفية من خلال عمليات تحويل المواقع الموثوقة

الأهم من ذلك أننا نضع الموقع على أداة منفصلة من أدوات تحليل المواقع، ويدخل الموقع في ذاكرة التخزين المؤقت لهذه المحللات، ثم الروابط المستلمة التي نضعها كتوجيه مرة أخرى على المدونات والمنتديات والتعليقات.

هذا العملية المهم يُبرز لمحركات البحث خارطة الموقع، حيث تعرض أدوات تحليل المواقع جميع المعلومات عن المواقع مع جميع الكلمات الرئيسية والعناوين وهو شيء جيد جداً

جميع المعلومات عن خدماتنا على الموقع!

Проститутки Москвы по районам devkiru.com

По вопросу [url=https://devkiru.com/kahovskaya]проститутки м каховская[/url] Вы на правильном пути. Наш проверенный веб портал оказывает превосходный отдых 18 плюс. Здесь есть: индивидуалки, массажистки, элитные красавицы, частные интим-объявления. А еще Вы можете найти требующуюся девочку по параметрам: по станции метро, по весу, росту, цвету волос, стоимости. Всё для Вашего комфорта.

[url=https://metforemin.online/]generic for metformin[/url]

Проститутки Москвы по районам devkiru.com

По теме [url=https://devkiru.com/shabolovskaya]проститутки шаболовская[/url] Вы на нужном пути. Наш проверенный интернет ресурс оказывает отборный отдых 18 плюс. Здесь есть: индивидуалки, массажистки, элитные красавицы, частные интим-объявления. А еще Вы можете отыскать желаемую девушку по параметрам: по станции метро, по весу, росту, адресу, карте. Всё для Вашего комфорта.

[url=http://azithromycinps.online/]azithromycin 250mg price in india[/url]

[url=http://bmtadalafil.online/]tadalafil capsule[/url]

I’m amazed, I must say. Rarely do I come across

a blog that’s equally educative and interesting, and without a doubt,

you’ve hit the nail on the head. The problem is something too few men and women are speaking intelligently about.

I’m very happy I found this during my search for something regarding this.

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added”

checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get

four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove people from that service?

Many thanks!

Way cool! Some extremely vlid points! I ɑppreciate yօu penning this article pluhs tһe rest of the website іs гeally gοod.

Аlso visit my web site Gopek178

rikvip

Rikvip Club: Trung Tâm Giải Trí Trực Tuyến Hàng Đầu tại Việt Nam

Rikvip Club là một trong những nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến hàng đầu tại Việt Nam, cung cấp một loạt các trò chơi hấp dẫn và dịch vụ cho người dùng. Cho dù bạn là người dùng iPhone hay Android, Rikvip Club đều có một cái gì đó dành cho mọi người. Với sứ mạng và mục tiêu rõ ràng, Rikvip Club luôn cố gắng cung cấp những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất cho khách hàng, tạo ra một trải nghiệm tiện lợi và thú vị cho người chơi.

Sứ Mạng và Mục Tiêu của Rikvip

Từ khi bắt đầu hoạt động, Rikvip Club đã có một kế hoạch kinh doanh rõ ràng, luôn nỗ lực để cung cấp cho khách hàng những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất và tạo điều kiện thuận lợi nhất cho người chơi truy cập. Nhóm quản lý của Rikvip Club có những mục tiêu và ước muốn quyết liệt để biến Rikvip Club thành trung tâm giải trí hàng đầu trong lĩnh vực game đổi thưởng trực tuyến tại Việt Nam và trên toàn cầu.

Trải Nghiệm Live Casino

Rikvip Club không chỉ nổi bật với sự đa dạng của các trò chơi đổi thưởng mà còn với các phòng trò chơi casino trực tuyến thu hút tất cả người chơi. Môi trường này cam kết mang lại trải nghiệm chuyên nghiệp với tính xanh chín và sự uy tín không thể nghi ngờ. Đây là một sân chơi lý tưởng cho những người yêu thích thách thức bản thân và muốn tận hưởng niềm vui của chiến thắng. Với các sảnh cược phổ biến như Roulette, Sic Bo, Dragon Tiger, người chơi sẽ trải nghiệm những cảm xúc độc đáo và đặc biệt khi tham gia vào casino trực tuyến.

Phương Thức Thanh Toán Tiện Lợi

Rikvip Club đã được trang bị những công nghệ thanh toán tiên tiến ngay từ đầu, mang lại sự thuận tiện và linh hoạt cho người chơi trong việc sử dụng hệ thống thanh toán hàng ngày. Hơn nữa, Rikvip Club còn tích hợp nhiều phương thức giao dịch khác nhau để đáp ứng nhu cầu đa dạng của người chơi: Chuyển khoản Ngân hàng, Thẻ cào, Ví điện tử…

Kết Luận

Tóm lại, Rikvip Club không chỉ là một nền tảng trò chơi, mà còn là một cộng đồng nơi người chơi có thể tụ tập để tận hưởng niềm vui của trò chơi và cảm giác hồi hộp khi chiến thắng. Với cam kết cung cấp những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất, Rikvip Club chắc chắn là điểm đến lý tưởng cho những người yêu thích trò chơi trực tuyến tại Việt Nam và cả thế giới.

Cá Cược Thể Thao Trực Tuyến RGBET

Thể thao trực tuyến RGBET cung cấp thông tin cá cược thể thao mới nhất, như tỷ số bóng đá, bóng rổ, livestream và dữ liệu trận đấu. Đến với RGBET, bạn có thể tham gia chơi tại sảnh thể thao SABA, PANDA SPORT, CMD368, WG và SBO. Khám phá ngay!

Giới Thiệu Sảnh Cá Cược Thể Thao Trực Tuyến

Những sự kiện thể thao đa dạng, phủ sóng toàn cầu và cách chơi đa dạng mang đến cho người chơi tỷ lệ cá cược thể thao hấp dẫn nhất, tạo nên trải nghiệm cá cược thú vị và thoải mái.

Sảnh Thể Thao SBOBET

SBOBET, thành lập từ năm 1998, đã nhận được giấy phép cờ bạc trực tuyến từ Philippines, Đảo Man và Ireland. Tính đến nay, họ đã trở thành nhà tài trợ cho nhiều CLB bóng đá. Hiện tại, SBOBET đang hoạt động trên nhiều nền tảng trò chơi trực tuyến khắp thế giới.

Xem Chi Tiết »

Sảnh Thể Thao SABA

Saba Sports (SABA) thành lập từ năm 2008, tập trung vào nhiều hoạt động thể thao phổ biến để tạo ra nền tảng thể thao chuyên nghiệp và hoàn thiện. SABA được cấp phép IOM hợp pháp từ Anh và mang đến hơn 5.000 giải đấu thể thao đa dạng mỗi tháng.

Xem Chi Tiết »

Sảnh Thể Thao CMD368

CMD368 nổi bật với những ưu thế cạnh tranh, như cung cấp cho người chơi hơn 20.000 trận đấu hàng tháng, đến từ 50 môn thể thao khác nhau, đáp ứng nhu cầu của tất cả các fan hâm mộ thể thao, cũng như thoả mãn mọi sở thích của người chơi.

Xem Chi Tiết »

Sảnh Thể Thao PANDA SPORT

OB Sports đã chính thức đổi tên thành “Panda Sports”, một thương hiệu lớn với hơn 30 giải đấu bóng. Panda Sports đặc biệt chú trọng vào tính năng cá cược thể thao, như chức năng “đặt cược sớm và đặt cược trực tiếp tại livestream” độc quyền.

Xem Chi Tiết »

Sảnh Thể Thao WG

WG Sports tập trung vào những môn thể thao không quá được yêu thích, với tỷ lệ cược cao và xử lý đơn cược nhanh chóng. Đặc biệt, nhiều nhà cái hàng đầu trên thị trường cũng hợp tác với họ, trở thành là một trong những sảnh thể thao nổi tiếng trên toàn cầu.

Xem Chi Tiết »

Fantastic beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your website, how could i subscribe for

a blog website? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I

had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright

clear idea

Euro 2024

UEFA Euro 2024 Sân Chơi Bóng Đá Hấp Dẫn Nhất Của Châu Âu

Euro 2024 là sự kiện bóng đá lớn nhất của châu Âu, không chỉ là một giải đấu mà còn là một cơ hội để các quốc gia thể hiện tài năng, sự đoàn kết và tinh thần cạnh tranh.

Euro 2024 hứa hẹn sẽ mang lại những trận cầu đỉnh cao và kịch tính cho người hâm mộ trên khắp thế giới. Cùng tìm hiểu các thêm thông tin hấp dẫn về giải đấu này tại bài viết dưới đây, gồm:

Nước chủ nhà

Đội tuyển tham dự

Thể thức thi đấu

Thời gian diễn ra

Sân vận động

Euro 2024 sẽ được tổ chức tại Đức, một quốc gia có truyền thống vàng của bóng đá châu Âu.

Đức là một đất nước giàu có lịch sử bóng đá với nhiều thành công quốc tế và trong những năm gần đây, họ đã thể hiện sức mạnh của mình ở cả mặt trận quốc tế và câu lạc bộ.

Việc tổ chức Euro 2024 tại Đức không chỉ là một cơ hội để thể hiện năng lực tổ chức tuyệt vời mà còn là một dịp để giới thiệu văn hóa và sức mạnh thể thao của quốc gia này.

Đội tuyển tham dự giải đấu Euro 2024

Euro 2024 sẽ quy tụ 24 đội tuyển hàng đầu từ châu Âu. Các đội tuyển này sẽ là những đại diện cho sự đa dạng văn hóa và phong cách chơi bóng đá trên khắp châu lục.

Các đội tuyển hàng đầu như Đức, Pháp, Tây Ban Nha, Bỉ, Italy, Anh và Hà Lan sẽ là những ứng viên nặng ký cho chức vô địch.

Trong khi đó, các đội tuyển nhỏ hơn như Iceland, Wales hay Áo cũng sẽ mang đến những bất ngờ và thách thức cho các đối thủ.

Các đội tuyển tham dự được chia thành 6 bảng đấu, gồm:

Bảng A: Đức, Scotland, Hungary và Thuỵ Sĩ

Bảng B: Tây Ban Nha, Croatia, Ý và Albania

Bảng C: Slovenia, Đan Mạch, Serbia và Anh

Bảng D: Ba Lan, Hà Lan, Áo và Pháp

Bảng E: Bỉ, Slovakia, Romania và Ukraina

Bảng F: Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, Gruzia, Bồ Đào Nha và Cộng hoà Séc

국외선물의 출발 골드리치와 동참하세요.

골드리치증권는 길고긴기간 고객님들과 함께 선물마켓의 진로을 공동으로 걸어왔으며, 고객분들의 확실한 자금운용 및 높은 이익률을 지향하여 계속해서 전력을 다하고 있습니다.

왜 20,000+명 이상이 골드리치와 동참하나요?

신속한 대응: 편리하고 빠른속도의 프로세스를 갖추어 누구나 간편하게 이용할 수 있습니다.

보안 프로토콜: 국가당국에서 적용한 높은 등급의 보안을 채택하고 있습니다.

스마트 인가: 전체 거래내용은 암호처리 가공되어 본인 외에는 그 누구도 정보를 열람할 수 없습니다.

보장된 수익률 공급: 리스크 요소를 낮추어, 더욱 한층 확실한 수익률을 제시하며 그에 따른 리포트를 공유합니다.

24 / 7 지속적인 고객지원: 365일 24시간 즉각적인 서비스를 통해 투자자분들을 온전히 뒷받침합니다.

협력하는 동반사: 골드리치증권는 공기업은 물론 금융기관들 및 다수의 협력사와 함께 걸어오고.

외국선물이란?

다양한 정보를 확인하세요.

외국선물은 외국에서 거래되는 파생금융상품 중 하나로, 지정된 기반자산(예: 주식, 화폐, 상품 등)을 기초로 한 옵션계약 계약을 말합니다. 본질적으로 옵션은 특정 기초자산을 향후의 어떤 시점에 일정 금액에 사거나 팔 수 있는 권리를 제공합니다. 외국선물옵션은 이러한 옵션 계약이 해외 마켓에서 거래되는 것을 뜻합니다.

국외선물은 크게 콜 옵션과 풋 옵션으로 나뉩니다. 콜 옵션은 지정된 기초자산을 미래에 일정 가격에 매수하는 권리를 부여하는 반면, 풋 옵션은 특정 기초자산을 미래에 정해진 금액에 팔 수 있는 권리를 허락합니다.

옵션 계약에서는 미래의 특정 날짜에 (만료일이라 칭하는) 일정 가격에 기초자산을 매수하거나 매도할 수 있는 권리를 보유하고 있습니다. 이러한 가격을 행사 가격이라고 하며, 만료일에는 해당 권리를 실행할지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다. 따라서 옵션 계약은 거래자에게 향후의 시세 변동에 대한 안전장치나 이익 창출의 기회를 허락합니다.

국외선물은 시장 참가자들에게 다양한 운용 및 매매거래 기회를 제공, 환율, 상품, 주식 등 다양한 자산유형에 대한 옵션 계약을 포함할 수 있습니다. 투자자는 풋 옵션을 통해 기초자산의 하향에 대한 안전장치를 받을 수 있고, 매수 옵션을 통해 활황에서의 이익을 타깃팅할 수 있습니다.

해외선물 거래의 원리

실행 금액(Exercise Price): 외국선물에서 실행 금액은 옵션 계약에 따라 명시된 가격으로 계약됩니다. 만기일에 이 금액을 기준으로 옵션을 행사할 수 있습니다.

종료일(Expiration Date): 옵션 계약의 만료일은 옵션의 행사가 불가능한 마지막 일자를 의미합니다. 이 일자 다음에는 옵션 계약이 소멸되며, 더 이상 거래할 수 없습니다.

매도 옵션(Put Option)과 매수 옵션(Call Option): 매도 옵션은 기초자산을 명시된 가격에 팔 수 있는 권리를 제공하며, 매수 옵션은 기초자산을 특정 가격에 매수하는 권리를 허락합니다.

프리미엄(Premium): 외국선물 거래에서는 옵션 계약에 대한 옵션료을 납부해야 합니다. 이는 옵션 계약에 대한 가격으로, 마켓에서의 수요량와 공급량에 따라 변경됩니다.

행사 방식(Exercise Strategy): 투자자는 만료일에 옵션을 행사할지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다. 이는 시장 상황 및 투자 플랜에 따라 다르며, 옵션 계약의 이익을 최대화하거나 손실을 최소화하기 위해 선택됩니다.

시장 위험요인(Market Risk): 외국선물 거래는 마켓의 변화추이에 작용을 받습니다. 시세 변동이 기대치 못한 진로으로 일어날 경우 손실이 발생할 수 있으며, 이러한 시장 리스크를 축소하기 위해 거래자는 전략을 수립하고 투자를 설계해야 합니다.

골드리치와 함께하는 국외선물은 안전하고 신뢰할 수 있는 운용을 위한 가장좋은 대안입니다. 투자자분들의 투자를 뒷받침하고 인도하기 위해 우리는 최선을 기울이고 있습니다. 공동으로 더 나은 내일를 향해 나아가요.

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my weblog thus i came to

“return the favor”.I’m attempting to find things to enhance my website!I suppose its ok

to use some of your ideas!!

Heya this is kind of of off topic but I was

wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML.

I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding experience

so I wanted to get advice from someone with experience.

Any help would be greatly appreciated!

Стремитесь к успеху в карьере и хотите обеспечить себе высокий доход? Наш сервис предлагает вам [url=https://kupi-diploms.ru/]купить диплом высшем Гознак[/url], который обладает высоким качеством и признанием на рынке труда. Если же вам интересны ретро-варианты, вы можете [url=https://kupi-diploms.ru/]купить старый диплом техникума[/url]. Наши дипломы – ваш ключ к успешной карьере и достойной заработной плате. Выбирая нас, вы выбираете надежность и профессионализм, подтвержденные множеством довольных клиентов.

Euro

UEFA Euro 2024 Sân Chơi Bóng Đá Hấp Dẫn Nhất Của Châu Âu

Euro 2024 là sự kiện bóng đá lớn nhất của châu Âu, không chỉ là một giải đấu mà còn là một cơ hội để các quốc gia thể hiện tài năng, sự đoàn kết và tinh thần cạnh tranh.

Euro 2024 hứa hẹn sẽ mang lại những trận cầu đỉnh cao và kịch tính cho người hâm mộ trên khắp thế giới. Cùng tìm hiểu các thêm thông tin hấp dẫn về giải đấu này tại bài viết dưới đây, gồm:

Nước chủ nhà

Đội tuyển tham dự

Thể thức thi đấu

Thời gian diễn ra

Sân vận động

Euro 2024 sẽ được tổ chức tại Đức, một quốc gia có truyền thống vàng của bóng đá châu Âu.

Đức là một đất nước giàu có lịch sử bóng đá với nhiều thành công quốc tế và trong những năm gần đây, họ đã thể hiện sức mạnh của mình ở cả mặt trận quốc tế và câu lạc bộ.

Việc tổ chức Euro 2024 tại Đức không chỉ là một cơ hội để thể hiện năng lực tổ chức tuyệt vời mà còn là một dịp để giới thiệu văn hóa và sức mạnh thể thao của quốc gia này.

Đội tuyển tham dự giải đấu Euro 2024

Euro 2024 sẽ quy tụ 24 đội tuyển hàng đầu từ châu Âu. Các đội tuyển này sẽ là những đại diện cho sự đa dạng văn hóa và phong cách chơi bóng đá trên khắp châu lục.

Các đội tuyển hàng đầu như Đức, Pháp, Tây Ban Nha, Bỉ, Italy, Anh và Hà Lan sẽ là những ứng viên nặng ký cho chức vô địch.

Trong khi đó, các đội tuyển nhỏ hơn như Iceland, Wales hay Áo cũng sẽ mang đến những bất ngờ và thách thức cho các đối thủ.

Các đội tuyển tham dự được chia thành 6 bảng đấu, gồm:

Bảng A: Đức, Scotland, Hungary và Thuỵ Sĩ

Bảng B: Tây Ban Nha, Croatia, Ý và Albania

Bảng C: Slovenia, Đan Mạch, Serbia và Anh

Bảng D: Ba Lan, Hà Lan, Áo và Pháp

Bảng E: Bỉ, Slovakia, Romania và Ukraina

Bảng F: Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, Gruzia, Bồ Đào Nha và Cộng hoà Séc

Rikvip Club: Trung Tâm Giải Trí Trực Tuyến Hàng Đầu tại Việt Nam

Rikvip Club là một trong những nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến hàng đầu tại Việt Nam, cung cấp một loạt các trò chơi hấp dẫn và dịch vụ cho người dùng. Cho dù bạn là người dùng iPhone hay Android, Rikvip Club đều có một cái gì đó dành cho mọi người. Với sứ mạng và mục tiêu rõ ràng, Rikvip Club luôn cố gắng cung cấp những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất cho khách hàng, tạo ra một trải nghiệm tiện lợi và thú vị cho người chơi.

Sứ Mạng và Mục Tiêu của Rikvip

Từ khi bắt đầu hoạt động, Rikvip Club đã có một kế hoạch kinh doanh rõ ràng, luôn nỗ lực để cung cấp cho khách hàng những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất và tạo điều kiện thuận lợi nhất cho người chơi truy cập. Nhóm quản lý của Rikvip Club có những mục tiêu và ước muốn quyết liệt để biến Rikvip Club thành trung tâm giải trí hàng đầu trong lĩnh vực game đổi thưởng trực tuyến tại Việt Nam và trên toàn cầu.

Trải Nghiệm Live Casino

Rikvip Club không chỉ nổi bật với sự đa dạng của các trò chơi đổi thưởng mà còn với các phòng trò chơi casino trực tuyến thu hút tất cả người chơi. Môi trường này cam kết mang lại trải nghiệm chuyên nghiệp với tính xanh chín và sự uy tín không thể nghi ngờ. Đây là một sân chơi lý tưởng cho những người yêu thích thách thức bản thân và muốn tận hưởng niềm vui của chiến thắng. Với các sảnh cược phổ biến như Roulette, Sic Bo, Dragon Tiger, người chơi sẽ trải nghiệm những cảm xúc độc đáo và đặc biệt khi tham gia vào casino trực tuyến.

Phương Thức Thanh Toán Tiện Lợi

Rikvip Club đã được trang bị những công nghệ thanh toán tiên tiến ngay từ đầu, mang lại sự thuận tiện và linh hoạt cho người chơi trong việc sử dụng hệ thống thanh toán hàng ngày. Hơn nữa, Rikvip Club còn tích hợp nhiều phương thức giao dịch khác nhau để đáp ứng nhu cầu đa dạng của người chơi: Chuyển khoản Ngân hàng, Thẻ cào, Ví điện tử…

Kết Luận

Tóm lại, Rikvip Club không chỉ là một nền tảng trò chơi, mà còn là một cộng đồng nơi người chơi có thể tụ tập để tận hưởng niềm vui của trò chơi và cảm giác hồi hộp khi chiến thắng. Với cam kết cung cấp những sản phẩm và dịch vụ tốt nhất, Rikvip Club chắc chắn là điểm đến lý tưởng cho những người yêu thích trò chơi trực tuyến tại Việt Nam và cả thế giới.

Стоимость проекта перепланировки зависит от множества факторов: сложности работ, размера помещения, необходимости согласования с различными инстанциями и других нюансов. Компания “КитСтрой” предлагает услуги по проектированию и согласованию перепланировок по доступным ценам. Мы предоставляем полную прозрачность ценообразования, чтобы вы могли заранее знать все затраты. Наши специалисты готовы помочь вам разработать оптимальный проект, который соответствует вашим потребностям и бюджету.

[url=https://potolki-kitstroy.ru/]Проект перепланировки стоимость[/url] с “КитСтрой” — это выгодное и качественное решение для вашего помещения. Мы обеспечиваем индивидуальный подход к каждому клиенту и гарантируем высокое качество выполняемых работ.

해외선물

외국선물의 시작 골드리치와 동행하세요.

골드리치는 길고긴기간 고객님들과 더불어 선물마켓의 길을 함께 여정을했습니다, 고객분들의 확실한 투자 및 알찬 수익성을 지향하여 항상 전력을 다하고 있습니다.

무엇때문에 20,000+명 이상이 골드리치증권와 함께할까요?

즉각적인 솔루션: 간단하며 빠른 프로세스를 갖추어 모두 용이하게 사용할 수 있습니다.

안전 프로토콜: 국가기관에서 적용한 최상의 등급의 보안시스템을 적용하고 있습니다.

스마트 인증: 모든 거래데이터은 암호화 가공되어 본인 이외에는 아무도 누구도 정보를 열람할 수 없습니다.

안전 이익률 제공: 위험 부분을 감소시켜, 더욱 한층 보장된 수익률을 제공하며 그에 따른 리포트를 발간합니다.

24 / 7 실시간 고객상담: året runt 24시간 실시간 상담을 통해 투자자분들을 모두 뒷받침합니다.

함께하는 파트너사: 골드리치는 공기업은 물론 금융계들 및 다양한 협력사와 함께 동행해오고.

해외선물이란?

다양한 정보를 참고하세요.

외국선물은 해외에서 거래되는 파생상품 중 하나로, 특정 기반자산(예: 주식, 화폐, 상품 등)을 기초로 한 옵션계약 약정을 지칭합니다. 본질적으로 옵션은 특정 기초자산을 미래의 어떤 시점에 일정 금액에 사거나 매도할 수 있는 자격을 부여합니다. 외국선물옵션은 이러한 옵션 계약이 해외 시장에서 거래되는 것을 의미합니다.

국외선물은 크게 콜 옵션과 풋 옵션으로 나뉩니다. 콜 옵션은 특정 기초자산을 미래에 일정 금액에 매수하는 권리를 허락하는 반면, 풋 옵션은 특정 기초자산을 미래에 정해진 금액에 팔 수 있는 권리를 부여합니다.

옵션 계약에서는 미래의 명시된 날짜에 (만료일이라 지칭되는) 일정 금액에 기초자산을 사거나 매도할 수 있는 권리를 가지고 있습니다. 이러한 금액을 실행 가격이라고 하며, 만기일에는 해당 권리를 행사할지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다. 따라서 옵션 계약은 투자자에게 미래의 가격 변화에 대한 안전장치나 이익 창출의 기회를 부여합니다.

해외선물은 마켓 참가자들에게 다양한 운용 및 매매거래 기회를 열어주며, 환율, 상품, 주식 등 다양한 자산유형에 대한 옵션 계약을 망라할 수 있습니다. 거래자는 풋 옵션을 통해 기초자산의 하향에 대한 보호를 받을 수 있고, 매수 옵션을 통해 활황에서의 수익을 노릴 수 있습니다.

국외선물 거래의 원리

행사 가격(Exercise Price): 외국선물에서 행사 금액은 옵션 계약에 따라 지정된 금액으로 계약됩니다. 만기일에 이 금액을 기준으로 옵션을 실행할 수 있습니다.

만기일(Expiration Date): 옵션 계약의 만료일은 옵션의 행사가 불가능한 최종 일자를 의미합니다. 이 일자 이후에는 옵션 계약이 종료되며, 더 이상 거래할 수 없습니다.

매도 옵션(Put Option)과 콜 옵션(Call Option): 매도 옵션은 기초자산을 지정된 가격에 매도할 수 있는 권리를 부여하며, 매수 옵션은 기초자산을 지정된 가격에 매수하는 권리를 부여합니다.

계약료(Premium): 국외선물 거래에서는 옵션 계약에 대한 계약료을 납부해야 합니다. 이는 옵션 계약에 대한 가격으로, 마켓에서의 수요와 공급량에 따라 변동됩니다.

실행 방안(Exercise Strategy): 투자자는 만기일에 옵션을 행사할지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다. 이는 마켓 상황 및 거래 플랜에 따라 다르며, 옵션 계약의 이익을 최대화하거나 손해를 최소화하기 위해 판단됩니다.

마켓 리스크(Market Risk): 외국선물 거래는 시장의 변화추이에 효과을 받습니다. 시세 변화이 기대치 못한 진로으로 일어날 경우 손해이 발생할 수 있으며, 이러한 마켓 위험요인를 감소하기 위해 투자자는 계획을 구축하고 투자를 설계해야 합니다.

골드리치증권와 함께하는 해외선물은 보장된 신뢰할 수 있는 운용을 위한 최적의 옵션입니다. 회원님들의 투자를 지지하고 가이드하기 위해 우리는 최선을 기울이고 있습니다. 공동으로 더 나은 미래를 향해 나아가요.

Can you tell us more about this? I’d like to find out more details.

https://cutt.ly/Tero9yI0

Unquestionably imagine tһat that уoᥙ saіd. Your favourite reason appeared

to Ƅe at the net the easiest tһing to Ƅe mindful of.

I ѕay to you, І ddefinitely ɡet annoyed аt the sɑmе time ɑs folks thіnk about worries tһat theу plainly

d᧐n’t recognize ɑbout. Үou managed tto hit tһe nail upon the highest aѕ neatly аs defined оut tһe whole thing ᴡith no need sіdе-effects , people ϲould take a signal.

Will ⅼikely be back to get more. Tһank you

Feel free to sirf to my web site … Arena333 Link Alternatif

darknet market list [url=https://mydarkmarket.com/ ]deep web drug store [/url] tor marketplace

Tһіs blog wаѕ… how do I ѕay it? Relevant!!

Ϝinally Ӏ’ve found sοmething tһat helped me. Kudos!

Μy һomepage :: Gopek178 Login

В нашем мире, где диплом – это начало удачной карьеры в любой области, многие стараются найти максимально простой путь получения образования. Важность наличия документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь диплом открывает двери перед любым человеком, желающим начать трудовую деятельность или учиться в каком-либо ВУЗе.

В данном контексте мы предлагаем быстро получить любой необходимый документ. Вы сможете купить диплом, что будет удачным решением для человека, который не смог завершить образование или потерял документ. диплом изготавливается с особой аккуратностью, вниманием к мельчайшим нюансам. В итоге вы получите полностью оригинальный документ.

Преимущества данного решения состоят не только в том, что можно быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организован удобно, с нашей поддержкой. Начав от выбора нужного образца до консультации по заполнению персональных данных и доставки в любой регион страны — все под абсолютным контролем квалифицированных специалистов.

Для тех, кто хочет найти быстрый и простой способ получить требуемый документ, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Заказать диплом – это значит избежать длительного обучения и сразу переходить к своим целям: к поступлению в университет или к началу трудовой карьеры.

http://www.diplomans-russia.ru

Hi mates, its great post regarding educationand entirely explained, keep it up all the time.

https://diplomans-russiyans.ru

В современном мире, где диплом становится началом успешной карьеры в любом направлении, многие пытаются найти максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Факт наличия официального документа переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь именно диплом открывает двери перед всеми, кто стремится начать трудовую деятельность или учиться в ВУЗе.

Предлагаем очень быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы имеете возможность заказать диплом нового или старого образца, что становится удачным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить обучение или утратил документ. дипломы производятся с особой тщательностью, вниманием к мельчайшим элементам, чтобы в итоге получился документ, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Превосходство этого решения состоит не только в том, что вы сможете оперативно получить диплом. Процесс организовывается комфортно и легко, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начиная от выбора подходящего образца диплома до правильного заполнения личной информации и доставки в любое место России — все находится под полным контролем квалифицированных специалистов.

В итоге, всем, кто хочет найти быстрый и простой способ получить требуемый документ, наша компания готова предложить отличное решение. Приобрести диплом – это значит избежать длительного обучения и не теряя времени перейти к достижению личных целей: к поступлению в университет или к началу удачной карьеры.

diploman-russiya.ru

Good day! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be okay.

I’m absolutely enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get

my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success.

If you know of any please share. Many thanks!

외국선물의 출발 골드리치증권와 함께하세요.

골드리치증권는 오랜기간 투자자분들과 함께 선물시장의 행로을 공동으로 여정을했습니다, 투자자분들의 확실한 자금운용 및 높은 이익률을 지향하여 언제나 최선을 기울이고 있습니다.

무엇때문에 20,000+명 이상이 골드리치와 함께할까요?

빠른 대응: 간단하며 빠른 프로세스를 갖추어 누구나 수월하게 활용할 수 있습니다.

안전 프로토콜: 국가기관에서 적용한 최상의 등급의 보안을 도입하고 있습니다.

스마트 인가절차: 전체 거래데이터은 암호처리 가공되어 본인 외에는 그 누구도 정보를 열람할 수 없습니다.

확실한 이익률 마련: 리스크 요소를 감소시켜, 더욱 더 확실한 수익률을 공개하며 이에 따른 리포트를 발간합니다.

24 / 7 지속적인 고객지원: 연중무휴 24시간 즉각적인 서비스를 통해 고객님들을 모두 지원합니다.

함께하는 동반사: 골드리치증권는 공기업은 물론 금융계들 및 다양한 협력사와 함께 여정을 했습니다.

해외선물이란?

다양한 정보를 확인하세요.

국외선물은 외국에서 거래되는 파생금융상품 중 하나로, 특정 기반자산(예: 주식, 화폐, 상품 등)을 기초로 한 옵션계약 계약을 말합니다. 근본적으로 옵션은 지정된 기초자산을 향후의 특정한 시점에 정해진 금액에 매수하거나 팔 수 있는 권리를 제공합니다. 외국선물옵션은 이러한 옵션 계약이 국외 마켓에서 거래되는 것을 의미합니다.

해외선물은 크게 매수 옵션과 풋 옵션으로 구분됩니다. 매수 옵션은 명시된 기초자산을 미래에 일정 가격에 사는 권리를 부여하는 반면, 풋 옵션은 지정된 기초자산을 미래에 일정 가격에 팔 수 있는 권리를 제공합니다.

옵션 계약에서는 미래의 특정 일자에 (종료일이라 지칭되는) 일정 가격에 기초자산을 사거나 매도할 수 있는 권리를 가지고 있습니다. 이러한 금액을 실행 가격이라고 하며, 만기일에는 해당 권리를 행사할지 여부를 판단할 수 있습니다. 따라서 옵션 계약은 거래자에게 미래의 시세 변동에 대한 보호나 수익 창출의 기회를 제공합니다.

국외선물은 마켓 참가자들에게 다양한 운용 및 매매거래 기회를 마련, 외환, 상품, 주식 등 다양한 자산군에 대한 옵션 계약을 포괄할 수 있습니다. 거래자는 풋 옵션을 통해 기초자산의 하락에 대한 안전장치를 받을 수 있고, 콜 옵션을 통해 활황에서의 수익을 타깃팅할 수 있습니다.

해외선물 거래의 원리

행사 금액(Exercise Price): 국외선물에서 행사 금액은 옵션 계약에 따라 지정된 금액으로 계약됩니다. 만료일에 이 금액을 기준으로 옵션을 실행할 수 있습니다.

만료일(Expiration Date): 옵션 계약의 만기일은 옵션의 행사가 허용되지않는 마지막 날짜를 뜻합니다. 이 날짜 이후에는 옵션 계약이 종료되며, 더 이상 거래할 수 없습니다.

풋 옵션(Put Option)과 매수 옵션(Call Option): 매도 옵션은 기초자산을 명시된 금액에 매도할 수 있는 권리를 부여하며, 콜 옵션은 기초자산을 특정 가격에 매수하는 권리를 부여합니다.

프리미엄(Premium): 국외선물 거래에서는 옵션 계약에 대한 계약료을 지불해야 합니다. 이는 옵션 계약에 대한 비용으로, 시장에서의 수요량와 공급량에 따라 변화됩니다.

행사 방안(Exercise Strategy): 거래자는 종료일에 옵션을 행사할지 여부를 선택할 수 있습니다. 이는 마켓 환경 및 거래 전략에 따라 차이가있으며, 옵션 계약의 수익을 극대화하거나 손실을 감소하기 위해 선택됩니다.

시장 위험요인(Market Risk): 외국선물 거래는 시장의 변동성에 작용을 받습니다. 가격 변화이 기대치 못한 방향으로 일어날 경우 손실이 발생할 수 있으며, 이러한 마켓 리스크를 축소하기 위해 거래자는 전략을 수립하고 투자를 설계해야 합니다.

골드리치증권와 함께하는 해외선물은 확실한 신뢰할 수 있는 투자를 위한 가장좋은 대안입니다. 회원님들의 투자를 지지하고 가이드하기 위해 우리는 최선을 기울이고 있습니다. 함께 더 나은 내일를 지향하여 나아가요.

ทดลองเล่นสล็อต

ทดลองเล่นสล็อต

[url=https://declomid.online/]clomid online fast delivery[/url]

Завершение учебы образования является важным этапом в карьере каждого человека, который определяет его перспективы и профессиональные возможности – [url=http://diplomvam.ru]www.diplomvam.ru[/url]. Диплом даёт доступ путь к свежим горизонтам и перспективам, гарантируя возможность к высококачественному получению знаний и высокопрестижным специальностям. В сегодняшнем мире, где в конкуренция на трудовом рынке постоянно увеличивается, наличие аттестата делает обязательным условием для выдающейся карьеры. Он подтверждает ваши знания, умения и навыки, умения и умения перед профессиональным сообществом и обществом в целом. Кроме того, диплом дарит веру в свои силы и укрепляет оценку себя, что способствует личностному и саморазвитию. Получение диплома также вложением в свое будущее, предоставляя стабильность и приличный уровень проживания. Поэтому отдавать надлежащее внимание получению образования и стремиться к его достижению, чтобы получить успеха и удовлетворение от собственной профессиональной деятельности.

Аттестат не лишь символизирует ваше образовательный уровень, но и демонстрирует вашу дисциплинированность, трудолюбие и упорство в достижении задач. Он представляет собой результатом усилий и труда, вложенных в учебу и саморазвитие. Получение диплома открывает перед вами новые перспективы возможностей, позволяя выбирать из множества карьерных путей и профессиональных направлений. Кроме того предоставляет вам основу знаний и навыков и умений, необходимых для для успешной деятельности в нынешнем обществе, насыщенном трудностями и изменениями. Более того, диплом является свидетельством вашей квалификации и экспертности, что повышает вашу привлекательность на трудовом рынке и открывает перед вами двери к лучшим возможностям для карьерного роста. Следовательно, получение диплома не только обогащает ваше личное развитие, но и раскрывает вами новые и возможности для достижения и мечтаний.

[url=http://enolvadex.com/]tamoxifen canada brand[/url]

І think that іѕ one of the so mudh imрortant info fߋr mе.

And i am satisfied reading yоur article. Ᏼut wanna observation οn few

ɡeneral tһings, Thhe website taste іs great, the articles iis in point of fact excellent :

D. Excellent task, cheers

Feeel free tо surf tߋ my site; {link slot gacor hari ini}

kw bocor88

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

https://writeablog.net/tuloefxfsu/h1-b-vazhlivist-iakostevogo-skla-far-farfarlight-dlia-bezpeki-na

Получение диплома считается основным моментом во пути каждого человека, определяет его будущее и профессиональные перспективы – [url=http://diplomvam.ru]diplomvam.ru[/url]. Аттестат даёт доступ путь к перспективным горизонтам и возможностям, гарантируя возможность к качественному образованию и высокооплачиваемым специальностям. В современном обществе, где в конкуренция на трудовом рынке постоянно увеличивается, имение аттестата становится необходимым требованием для успешной карьеры. Диплом утверждает ваши знания, компетенции и компетенции перед работодателями и общественностью в общем. Помимо этого, аттестат придает уверенность и укрепляет самооценку, что содействует личностному и саморазвитию. Окончание образования также вложением в будущее, предоставляя устойчивость и достойный уровень проживания. Именно поэтому отдавать должное внимание получению образования и стремиться к его получению, чтобы обрести успех и счастье от своей труда.

Диплом не лишь представляет личное образование, но и отражает вашу дисциплинированность, усердие и настойчивость в добивании целей. Диплом является плодом труда и труда, вкладываемых в учебу и самосовершенствование. Завершение учебы образования открывает перед вами новые перспективы перспектив, позволяя выбирать среди разнообразия направлений и карьерных траекторий. Кроме того предоставляет вам базис знаний и умений, необходимых для выдающейся деятельности в современном обществе, полном трудностями и переменами. Более того, сертификат считается доказательством вашей компетентности и экспертности, что в свою очередь повышает вашу привлекательность для работодателей на рынке труда и открывает вами возможности к лучшим шансам для карьерного роста. Итак, получение образования аттестата не только пополняет ваше личное и профессиональное самосовершенствование, а также открывает перед вами новые и перспективы для достижения и амбиций.

Завершение учебы диплома является основным этапом в карьере каждого индивидуума, определяющим его будущее и карьерные возможности – [url=http://diplomvam.ru]www.diplomvam.ru[/url]. Аттестат даёт доступ путь к свежим горизонтам и перспективам, обеспечивая доступ к качественному образованию и высокооплачиваемым специальностям. В сегодняшнем мире, где в конкуренция на трудовом рынке постоянно увеличивается, имение диплома становится необходимым условием для выдающейся карьеры. Диплом утверждает ваши знания, умения и навыки, умения и умения перед работодателями и социумом в целом. Помимо этого, диплом дарует уверенность и повышает самооценку, что содействует личностному росту и саморазвитию. Завершение учебы диплома также является вложением в свое будущее, предоставляя устойчивость и достойный уровень жизни. Поэтому важно отдавать надлежащее внимание получению образования и бороться за его получению, чтобы получить успеха и счастье от своей профессиональной деятельности.

Диплом не лишь символизирует личное образование, но и отражает вашу дисциплинированность, усердие и упорство в добивании задач. Диплом является результатом труда и труда, вкладываемых в учебу и саморазвитие. Получение образования открывает перед вами новые горизонты возможностей, даруя возможность избирать среди множества направлений и карьерных траекторий. Помимо этого предоставляет вам основу знаний и навыков и навыков, необходимых для успешной деятельности в современном мире, насыщенном трудностями и изменениями. Помимо этого, диплом считается свидетельством вашей квалификации и экспертности, что повышает вашу привлекательность для работодателей на трудовом рынке и открывает перед вами двери к наилучшим шансам для профессионального роста. Следовательно, завершение учебы диплома не лишь обогащает ваше личное и профессиональное самосовершенствование, но и открывает перед вами новые и возможности для достижения целей и мечтаний.

Поможем Вам купить диплом Вуза России недорого, без предоплаты и с гарантией возврата средств

http://www.diplomans-rossian.com

[url=https://accutaneiso.online/]buy accutane online india[/url]

Завершение учебы образования считается важным моментом во жизни всякого индивидуума, определяющим его перспективы и карьерные возможности – [url=http://diplomvam.ru]http://diplomvam.ru[/url]. Аттестат даёт доступ двери к свежим горизонтам и перспективам, гарантируя возможность к высококачественному образованию и престижным специальностям. В современном мире, где в борьба на трудовом рынке постоянно увеличивается, наличие аттестата становится жизненно важным условием для выдающейся профессиональной деятельности. Диплом утверждает ваши знания, умения и навыки, умения и умения перед работодателями и обществом в целом. Помимо этого, аттестат дарит веру в свои силы и увеличивает оценку себя, что помогает личностному и саморазвитию. Окончание образования также инвестицией в будущее, обеспечивая стабильность и достойный уровень проживания. Поэтому важно уделять должное внимание и время получению образования и стремиться к его достижению, чтобы получить успех и счастье от собственной профессиональной деятельности.