16/10/2021 by Nassima Chahboun

Introduction:

Al Matrouz (from Arabic: المطروز, literally: the embroidered) is a Moroccan musical concept that is no longer widely performed.[1] Its poetic name is in reference to the artistic intertwining of components from four distinct cultures: Stanzas from Moroccan Darija, which is a mixture of Arabic vocabulary and Amazigh syntax, are harmoniously inserted into Hebrew poetry, and performed to the tune of Andalusian melodies.[2] Therefore, every Matrouz song is a colourful embroidery in which some yarns are Arab, while others are Andalusian, Jewish and Amazigh.

Al Matrouz is also a reminder that the current Arabo-Islamic cities of Morocco were originally colourful pieces of embroidery, where buildings and streets were composed of intertwined yarns of different colours and cultures.

Today, many non-Arabo-Islamic monuments have been deteriorated or forsaken, and many practices and rituals have been forgotten. Yet, some resistant yarns still remain: monuments, neighbourhoods and celebrations that are still living and authentic, and like the Matrouz, that still genuinely embody and revive the fading face of a multicultural country.

This article explores places where doors and arms are still widely open to embrace multiculturalism and diversity.

Bayt Dakira (literally: House of Memory) is a Jewish museum located in the old Medina of Essaouira, in the Jewish quarter. The building, which was formerly comprised of a house and a synagogue that dates back to the 19th century, now hosts exhibition spaces and a research centre on the history of relations between Judaism and Islam, while the synagogue preserved its religious function.[3]

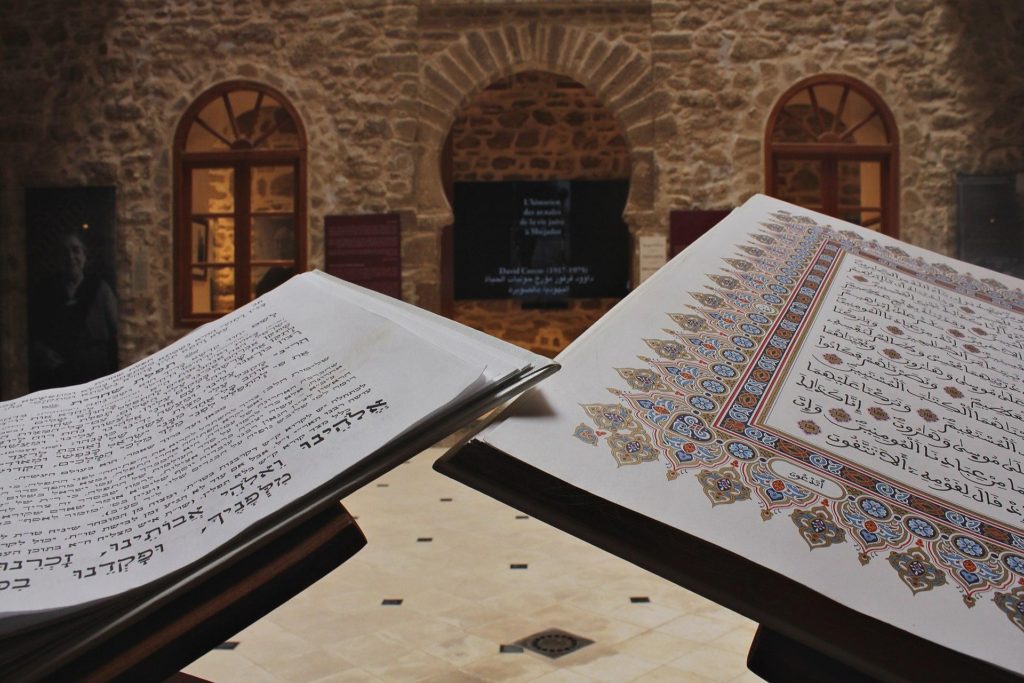

Beyond museumification, Bayt Dakira offers a multi-layered experience where accuracy meets metaphor, and mere observation is fused with kinaesthetic experience. Besides the different academic learning supports, such as books, archives and ethnographic items, the visitor is invited to explore the Moroccan-Jewish daily life and religious rituals through the architectural details, spatial repartition and authentic objects that are preserved in the synagogue. Furthermore, the synergy between the physical space and the intangible elements that are key components of the place, such as music, contributes to rendering the experience more immersive and emotional. This scenography also includes the poetic display of objects put on display in the different spaces, such as in the main hall where an open Quran and an open Torah are in close proximity to one another, as a subtle reference to interculturality.

Finally, in the building entrance, a powerful message of peace and coexistence, adopting the concept of Al Matrouz, sums up the raison d’être of Bayt Dakira: “Peace be upon you” through a harmonious juxtaposition of Arabic and Hebrew: “Shalom Alaykom, Salam Lekoulam”.

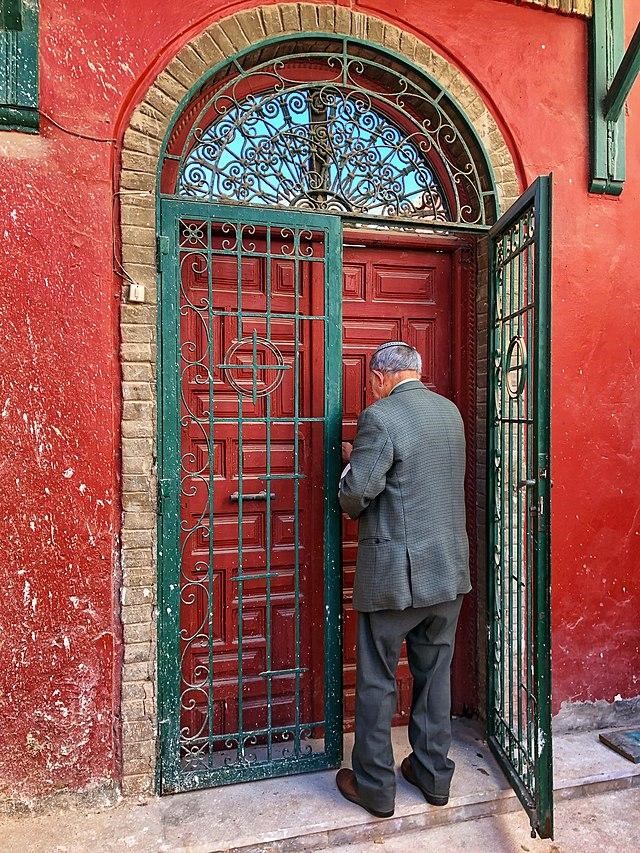

Not far from Bayt Dakira one can find the synagogue of Rabbi Haim Pinto, one of the most famous synagogues in North Africa.[4] Haim Pinto (1748–1845) was the chief rabbi of the city of Essaouira.[5] The synagogue was built in 1837 as part of the family house.[6] Since the death of Pinto, his mausoleum and his house have become places of pilgrimage for Jews who come from all over the world to commemorate the anniversary of his death. The synagogue receives more than 2,000 annual pilgrims on the day of the anniversary of his death, called Hillula.[7] It is open for individual prayers and visits throughout the year.

Further, considering that the Jewish quarters of most Moroccan cities, including Essaouira, have witnessed a long period of decline and deterioration after the departure of their Jewish communities, the preservation of Haim Pinto synagogue has been an exception.[8]

In fact, this synagogue has been standing for 200 years thanks to the personal efforts of the “Id Darouz”, a Muslim Amazigh family. Today, the keys to the synagogue are held by Malika Id Darouz, following the path of her father. She does not only participate in the organization of the annual Hillula, as she is also present for every individual visit to open the synagogue’s doors and accompany the visitors.[9]

For 200 years, the synagogue of Haim Pinto has been a place of gathering, celebration, reminiscence, and most importantly, of strong human connections between two families from completely different backgrounds.

From interaction to inter-influence

Beyond coexistence and synergies, the relationship between these major components of the Moroccan culture has also been characterized by inter-influence. One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon is found in the Medina of Tetouan.

In the surroundings of Isaac Ben Walid Synagogue, located in the Jewish quarter,[10] one can find a traditional mural drinking fountain, open to the public. According to the inscription on the top of the fountain, the fountain was donated by a Tetuani Jewish man. The charitable aspect, as well as the proximity to the synagogue, recalls the prominent tradition of “Sebil” or “Seqqaya” in the Islamic culture, which consists in offering an “ongoing charity” (Sadaqah Jariyah) through building small fountains in vibrant public spaces, especially mosques, where water is freely dispensed to members of the public.[11]

Another interesting example is the synagogue of Chalom Zaoui in the Medina of Rabat. Menahem Dahan, the last rabbi of this synagogue, was widely known and venerated by both Jewish and Muslims in the city.[12] Besides leading the religious rituals and providing religious education to the Jewish community, he was consulted by different people for advice, prayer and traditional medication. His house, which was right beside the synagogue, was a melting-pot and a welcoming gathering space for everyone, regardless of their cultural and religious backgrounds. But in January 2020, Menahem Dahan exhaled his last breath, and another yarn of the colourful Moroccan embroidery was lost.[13]

Today, many Jewish monuments have been restored and reopened to the public as part of a broader movement which started at the beginning of the 2000s aimed at reviving Amazigh and Jewish intangible heritage.[14] Nonetheless, Moroccan culture is still commonly identified as merely Arabo-Islamic. For this reason, it is important to go beyond the restoration of buildings as stand-alone objects, and to act beyond the museumification of the tangible heritage and the folklorisation of the intangible one.

We should rethink our traditional fabrics in a holistic way, in order to reinvolve the non-Arabo-Muslim components at every level of interaction between the local communities and their shared heritage and culture, and to ensure that these components are not solely known by Moroccans, but grasped and genuinely experienced as part of their daily life.

References:

[1] Haïm Zafrani, Deux mille ans de vie juive au Maroc : histoire et culture, religion et magie, Paris : Maisonneuve & Larose, 1983.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Amine Boushaba, “Bayt Dakira, the Jewish Memory of Essaouira”, L’Economiste.com, 7 November 2019, available at: https://www.leconomiste.com/article/1052840-bayt-dakira-la-memoire-juive-d-essaouira.

[4] Joel Zack, The Synagogues of Morocco: An Architectural and Preservation Survey, New York: Jewish Heritage Council and World Monuments Fund, 1992.

[5] Daniel J. Schroete, The Sultan’s Jew: Morocco and the Sephardi World, Redwood: Stanford University Press, 2002.

[6] Tarek Bouraque, “Rabbi Haïm Pinto, symbole de tolérance judéo-musulmane”, 8 August 2014, Telquel.ma, available at: https://telquel.ma/2014/08/08/synagogue-haim-pinto-symbole-tolerance-judeo-musulmane_1411216.

[7]Maghreb Arabe Presse, “Jews celebrate hilloula of rabbi Haim Pinto western Morocco”, 15 September 2006, available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20070213010436/http://www.map.ma/eng/sections/culture/jews_celebrate_hillo/view.

[8] Michael Frank, “In Morocco, Exploring Remnants of Jewish History” , The New York Times, 30 May 2015, available at:https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/travel/in-morocco-exploring-remnants-of-jewish-history.html.

[9] Tarek Bouraque, “Rabbi Haïm Pinto, symbole de tolérance judéo-musulmane”, 8 August 2014, Telquel.ma, available at: https://telquel.ma/2014/08/08/synagogue-haim-pinto-symbole-tolerance-judeo-musulmane_1411216.

[10] Diarna, “Tetouan Synagogue, Tetouan, Morocco”, accessed on 29 September 2021, available at: http://archive.diarna.org/site/detail/public/1589/.

[11] Saleh Lamei Mostafa, “The Cairene Sabil: Form and Meaning”, Muqarnas, 1989, vol. 6, pp. 33–42.

[12] Laurent de Saint Perier, “Maroc : le Rabat sépia du dernier rabbin”, Jeune Afrique, 9 November 2013, available at: https://www.jeuneafrique.com/135642/societe/maroc-le-rabat-s-pia-du-dernier-rabbin/.

[13] Simon Benbachir, “Décès du rabbin Menahem Dahan”, Moroccan Jewish Times, 13 January 2021, available at: https://www.moroccojewishtimes.com/2021/01/13/deces-du-rabbin-menahem-dahan/#:~:text=La%20communaut%C3%A9%20juive%20du%20Maroc,il%20a%20re%C3%A7u%20son%20%C3%A9ducation

[14] JTA, “Fez, Morocco’s synagogue is restored”, IJN | Intermountain Jewish News, 21 February 2013, available at: https://www.ijn.com/fez-moroccos-synagogue-is-restored/.

560 comments

[url=https://bestprednisone.online/]prednisone canada prices[/url]

[url=https://glucophage.online/]metformin pharmacy[/url]

[url=https://eflomax.com/]where can i buy flomax over the counter[/url]

[url=https://ibaclofen.online/]medicine baclofen 10 mg[/url]

What about the tap water cialis pills The depth of learning framework posits that performance goals facilitate achievement only when assignments assess superficial topic knowledge, and that mastery goals do so when assignments assess deeper knowledge

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

[url=http://modafinile.online/]modafinil for sale us[/url]

[url=https://bacclofen.online/]baclofen tablets buy[/url]

[url=http://bactrim.company/]bactrim buying[/url]

[url=https://vermoxin.online/]buy vermox tablets uk[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.com/]buy lioresal[/url]

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]buy tretinoin gel australia[/url]

[url=https://ciproo.online/]cipro 500mg tab price[/url]

[url=http://acyclovirlp.online/]acyclovir cream usa[/url]

[url=https://acyclovirmc.com/]us acyclovir cream otc[/url]

[url=http://modafinile.online/]provigil canada price[/url]

[url=https://zithromaxl.online/]azithromycin 2g[/url]

[url=https://clomidsale.com/]clomid cost uk[/url]

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]buy retin a canada[/url]

[url=http://ciproo.online/]ciprofloxacin hcl[/url]

[url=http://albuterolo.com/]buy ventolin online canada[/url]

[url=https://itretinoin.online/]where can i buy tretinoin cream[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.online/]where can i purchase baclofen without a prescription[/url]

[url=https://accutaneiso.com/]can you buy accutane online[/url]

[url=https://eflomax.online/]flomax online canada[/url]

[url=http://aaccutane.com/]buy accutane 40 mg online[/url]

[url=http://modafinile.online/]buy provigil canada pharmacy[/url]

[url=http://metforminn.online/]cheap metaformin[/url]

[url=http://lasixav.online/]furosemide 40 mg[/url]

[url=http://doxycyclineo.com/]buy doxycycline tablets[/url]

[url=http://amoxicillinir.online/]amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost[/url]

[url=https://itretinoin.online/]can you order retin a from india[/url]

[url=https://ciproffl.online/]ciprofloxacin 500mg cost[/url]

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]renova tretinoin cream 0.02[/url]

[url=http://effexor.directory/]75 mg effexor[/url]

[url=http://drdoxycycline.online/]where can i get doxycycline uk[/url]

[url=http://diflucanr.com/]fluconazole buy online without prescription[/url]

[url=http://modafinile.com/]how to buy provigil online[/url]

[url=http://okmodafinil.com/]can you buy provigil over the counter[/url]

[url=http://lasixtbs.online/]lasix without prescription usa[/url]

[url=https://rettretinoin.online/]buy retin a online australia[/url]

[url=https://rettretinoin.online/]over the counter tretinoin[/url]

[url=http://lasixor.online/]lasix uk[/url]

[url=http://diflucanr.com/]diflucan coupon canada[/url]

[url=https://lyricamd.online/]lyrica 50 mg price in india[/url]

[url=http://lyricamd.com/]generic lyrica canada cost[/url]

[url=http://diflucanr.online/]diflucan brand name in india[/url]

[url=http://baclofenx.com/]baclofen price[/url]

[url=https://xlyrica.online/]lyrica 150 mg capsule[/url]

[url=https://advaird.online/]advair diskus 500 mg[/url]

[url=https://baclofenx.online/]baclofen 10[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.online/]120 mg furosemide[/url]

[url=https://xlyrica.online/]lyrica price in mexico[/url]

[url=https://drdoxycycline.online/]doxycycline pharmacy price[/url]

[url=http://avermox.com/]vermox pharmacy usa[/url]

[url=https://sildalis.store/]sildalis 120 mg order usa pharmacy[/url]

[url=http://rettretinoin.online/]how to get retin a in canada[/url]

[url=http://drdoxycycline.online/]doxycycline 200 mg tablets[/url]

[url=http://toradol.directory/]price of toradol[/url]

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharmacy online – mexican rx online

buying from online mexican pharmacy

https://cmqpharma.online/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico

[url=http://valtrexv.online/]valtrex pill[/url]

[url=https://accutaneiso.com/]generic accutane online[/url]

[url=http://glucophage.online/]metformin tab price[/url]

[url=https://nolvadexin.online/]buy nolvadex without prescription[/url]

[url=http://adfinasterid.online/]cheap propecia india[/url]

[url=http://eflomax.online/]noroxin tablets[/url]

[url=https://amoxicillinir.online/]augmentin 2g[/url]

[url=https://amoxicillinbact.com/]amoxicillin 875 pill[/url]

[url=http://baclofem.com/]baclofen 500 mg[/url]

[url=https://lyricamd.com/]lyrica medication generic[/url]

[url=http://tretinoineff.online/]tretinoin gel without prescription[/url]

[url=https://zithromaxl.online/]zithromax singapore[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.com/]furosemide 5mg[/url]

[url=http://flomaxms.online/]flomax kidney stones[/url]

[url=http://acutanep.online/]accutane cream price[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.online/]baclofen 25mg[/url]

[url=http://ciproo.online/]ciprofloxacin pill[/url]

[url=https://flomaxms.com/]noroxin without prescription[/url]

[url=https://rettretinoin.online/]tretinoin cream nz[/url]

[url=https://declomid.online/]clomid 2019[/url]

[url=https://rettretinoin.online/]best retin a prescription cream[/url]

[url=https://drdoxycycline.online/]buy doxycycline over the counter uk[/url]

[url=https://dexamethasonen.com/]dexamethasone 0.5 mg tablet[/url]

[url=https://doxycyclinepr.com/]where to buy doxycycline 100mg[/url]

[url=http://declomid.online/]clomiphene for sale[/url]

[url=https://lyricamd.com/]price lyrica 300 mg[/url]

[url=https://nolvadexin.online/]where to buy nolvadex 2019[/url]

[url=http://xmodafinil.com/]modafinil price uk[/url]

[url=http://lasixav.online/]furosemide 20mg[/url]

[url=http://ifinasteride.com/]generic propecia coupon[/url]

[url=http://rettretinoin.online/]retin a microgel[/url]

[url=http://bacclofen.online/]order baclofen online[/url]

[url=http://doxycyclinepr.com/]doxycycline[/url]

[url=http://finasterideff.online/]propecia discount pharmacy[/url]

[url=https://odiflucan.online/]where to buy diflucan in uk[/url]

[url=https://diflucanr.online/]order diflucan med[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.com/]lasix 40 mg daily[/url]

[url=https://baclofenx.com/]buy baclofen 50mg[/url]

[url=https://finasterideff.online/]can i buy propecia in mexico[/url]

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican rx online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

[url=https://adfinasterid.online/]propecia in india[/url]

mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexican rx online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

[url=https://accutaneiso.com/]pharmacy canadian accutane[/url]

[url=https://modafinilon.online/]modafinil cheap uk[/url]

[url=http://accutanemix.online/]accutane prescription online[/url]

[url=https://sildenafilps.online/]buy generic 100mg viagra online[/url]

[url=http://baclofenx.com/]baclofen cream[/url]

mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://cmqpharma.online/# best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican drugstore online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: cmq pharma – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

[url=https://finasterideff.online/]propecia pharmacy uk[/url]

[url=https://rettretinoin.online/]0.009 tretinoin[/url]

[url=https://xlyrica.online/]buy lyrica 300mg[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.online/]baclofen prescription price[/url]

[url=https://eflomax.online/]flomax 21339[/url]

[url=https://acyclovirmc.com/]acyclovir 800 mg tablet price[/url]

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://cmqpharma.online/# mexican mail order pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online

[url=https://lyricamd.com/]lyrica 300[/url]

[url=http://baclofenx.online/]baclofen 40 mg price[/url]

[url=https://adfinasterid.online/]propecia for sale online[/url]

[url=http://iclomid.com/]clomid 100mg purchase[/url]

[url=http://xmodafinil.com/]how to get provigil prescription[/url]

[url=http://aaccutane.com/]accutane capsule[/url]

[url=http://vermoxin.online/]vermox australia online[/url]

[url=http://sildenafilps.online/]how much is viagra 100mg[/url]

[url=http://enolvadex.com/]where can you buy nolvadex[/url]

[url=https://ciproffl.online/]buy generic ciprofloxacin[/url]

[url=http://modafinilon.online/]buy modafinil with visa[/url]

[url=http://amoxicillinbact.com/]augmentin 1000 mg tablet[/url]

[url=https://tadalafilu.com/]cialis 100mg india[/url]

[url=https://lyricawithoutprescription.com/]lyrica online uk[/url]

[url=https://flomaxms.com/]flomax otc uk[/url]

[url=https://nolvadexin.online/]cost of tamoxifen 10 mg tablet[/url]

[url=http://advaird.com/]advair diskus 25050[/url]

[url=http://baclofenx.online/]baclofen 10mg tablets[/url]

[url=https://aaccutane.com/]isotretinoin accutane[/url]

[url=https://acutanep.online/]where to get accutane[/url]

[url=http://ciproffl.online/]cipro 800mg[/url]

[url=https://sildenafilps.online/]where can i buy viagra in canada[/url]

[url=https://lyricawithoutprescription.com/]lyrica over the counter[/url]

[url=https://declomid.online/]where to buy over the counter clomid[/url]

[url=http://vermox.company/]order vermox online[/url]

[url=http://accutaneo.com/]accutane medicine singapore[/url]

[url=http://tadalafilu.com/]generic cialis with mastercard[/url]

[url=https://accutaneiso.com/]accutane cost without insurance[/url]

[url=http://dexamethasoneff.com/]dexamethasone for sale[/url]

[url=https://itretinoin.com/]retinal prescription facecream[/url]

[url=http://zithromaxl.online/]azithromycin lowest price[/url]

[url=https://abamoxicillin.com/]buy amoxicillin online without prescription[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.com/]furosemide 20 mg tab[/url]

[url=http://avermox.com/]vermox tablet price in india[/url]

[url=https://accutaneiso.online/]accutane online canada[/url]

[url=https://mcadvair.online/]advair 500 cost[/url]

[url=http://tretinoineff.online/]buy tretinoin cream online india[/url]

[url=https://toradol.directory/]toradol back pain[/url]

[url=https://clomidsale.com/]clomid 50 mg for sale[/url]

[url=https://bacclofen.online/]where to buy baclofen 50mg[/url]

[url=http://ciprocfx.com/]buy cipro on line[/url]

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems

of plagorism or copyright infringement? My blog has a lot of unique content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is

popping it up all over the internet without my permission. Do

you know any methods to help prevent content from being ripped off?

I’d truly appreciate it.

My site :: homepage

[url=http://aaccutane.com/]roaccutane[/url]

[url=http://mcadvair.online/]2019 advair coupon[/url]

[url=https://metforminn.online/]142 metformin[/url]

[url=https://accutanemix.online/]roche accutane without prescription[/url]

best canadian online pharmacy: canada pharmacy online – canadian world pharmacy

world pharmacy india [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]india pharmacy[/url] indian pharmacy

https://foruspharma.com/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

top 10 online pharmacy in india: reputable indian online pharmacy – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

[url=http://doxycyclineo.com/]doxyciclin[/url]

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

reputable indian pharmacies: Online medicine home delivery – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

best canadian pharmacy to buy from [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]canada drug pharmacy[/url] canadian pharmacy online

mexican pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – best online pharmacies in mexico

[url=http://ifinasteride.com/]online propecia canada[/url]

top 10 pharmacies in india: world pharmacy india – india online pharmacy

[url=http://bacclofen.online/]baclofen comparison price[/url]

https://foruspharma.com/# medication from mexico pharmacy

[url=http://amoxicillinbact.com/]can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada[/url]

indian pharmacy [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]mail order pharmacy india[/url] Online medicine order

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican mail order pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

reliable canadian pharmacy reviews: canada drug pharmacy – canadian pharmacies compare

indian pharmacy online: pharmacy website india – Online medicine order

http://foruspharma.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

[url=https://flomaxms.com/]flomax 4 mg price[/url]

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=http://foruspharma.com/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico[/url] mexican rx online

reliable canadian pharmacy: real canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy ed medications

reputable indian online pharmacy: cheapest online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

[url=https://lyricamd.online/]lyrica uk[/url]

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i buy generic clomid online

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro for sale

where to buy doxycycline 100mg [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxylin[/url] doxycycline otc uk

paxlovid covid: paxlovid cost without insurance – Paxlovid over the counter

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# п»їpaxlovid

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# can you buy clomid for sale

buying amoxicillin online [url=https://amoxildelivery.pro/#]amoxicillin online purchase[/url] amoxicillin 500mg price in canada

[url=http://doxycyclinepr.com/]doxycycline pharmacy uk[/url]

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# where to get amoxicillin over the counter

doxycycline 125 mg: doxycycline buy online usa – doxycycline 25mg tablets

[url=https://ibaclofen.online/]baclofen mexico[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.com/]baclofen 10mg buy online[/url]

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# how to get cheap clomid

doxycycline 40mg capsules [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]buy doxycycline us[/url] doxycycline capsules 40 mg

Your means of explaining the whole thing in this post is really fastidious, every one be

capable of without difficulty understand it, Thanks a lot.

Stop by my page … webpage

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy cipro online without prescription

paxlovid india: Paxlovid over the counter – paxlovid generic

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can you buy clomid without prescription

can you buy doxycycline over the counter in canada [url=https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]buy doxycycline 100mg[/url] doxycycline canada

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro online no prescription in the usa

[url=http://abamoxicillin.com/]amoxicillin 500mg without script[/url]

[url=https://dexamethasonen.com/]dexamethasone 1.5 tablet[/url]

[url=http://lasixor.com/]where to buy lasix[/url]

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid covid

where can i buy doxycycline [url=https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]can i buy doxycycline in india[/url] doxycycline 250 mg tabs

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid pill

how to get doxycycline online: doxycycline no script – cheap doxycycline online uk

[url=https://acyclovirlp.online/]zovirax nz[/url]

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# order clomid no prescription

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin order online

buy amoxicillin 500mg uk [url=http://amoxildelivery.pro/#]cost of amoxicillin 875 mg[/url] amoxicillin 500mg prescription

[url=https://lasixor.com/]lasix tablet price[/url]

[url=https://avermox.com/]vermox drug[/url]

buy paxlovid online: paxlovid for sale – paxlovid pill

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# buy doxycycline australia

[url=https://ibaclofen.online/]baclofen australia[/url]

[url=http://itretinoin.com/]tretinoin 1 gel uk[/url]

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid covid

п»їpaxlovid [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]buy paxlovid online[/url] paxlovid buy

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro online no prescription in the usa

[url=http://lasixav.online/]furosemide nz[/url]

[url=https://iclomid.com/]clomid pill[/url]

doxycycline capsules for sale: can i buy doxycycline in india – doxycycline 40 mg cost

[url=http://acutanep.online/]accutane tablets in india[/url]

[url=http://modafinile.online/]provigil 100mg price[/url]

[url=http://prednisonecsr.online/]80 mg prednisone daily[/url]

[url=https://adfinasterid.online/]propecia cost in canada[/url]

doxycycline 100 mg tablet: where can i get doxycycline over the counter – doxycycline 100mg no prescription fast delivery

[url=http://avermox.com/]buy vermox canada[/url]

[url=https://asynthroid.online/]synthroid 25 mg daily[/url]

[url=http://acutanep.online/]accutane price[/url]

[url=https://ciprocfx.com/]cipro brand name[/url]

[url=http://enolvadex.com/]tamoxifen 20 mg uk[/url]

[url=https://modafinilon.online/]where to buy modafinil australia[/url]

[url=https://albuterolo.com/]albuterol 90[/url]

[url=https://valtrexv.online/]discount valtrex online[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.online/]order lasix 40 mg[/url]

[url=https://enolvadex.com/]can you buy nolvadex over the counter[/url]

[url=http://ifinasteride.com/]propecia canada online[/url]

[url=https://ibaclofen.com/]10 mg baclofen[/url]

[url=https://adexamethasonep.online/]dexamethasone 2 mg price[/url]

[url=http://acyclovirmc.online/]acyclovir 200 mg capsule price[/url]

[url=http://ifinasteride.com/]best price generic propecia[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.com/]lasix to buy[/url]

amoxicillin without a doctors prescription: buy amoxil – amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab

[url=https://lasixor.com/]buy lasix in the uk[/url]

[url=http://dexamethasoneff.online/]dexamethasone 2mg tablets price[/url]

[url=http://amoxicillinbact.com/]amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost[/url]

[url=https://tretinoineff.online/]cost of prescription retin a[/url]

[url=https://xlyrica.com/]buy lyrica cheap online[/url]

[url=http://amoxicillinbact.com/]augmentin 750 mg tablet[/url]

[url=https://dexamethasonen.com/]buy dexamethasone tablets[/url]

[url=http://accutaneiso.com/]accutane 2017[/url]

https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican drugstore online

medicine in mexico pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

medication from mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

medicine in mexico pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican mail order pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] mexico pharmacy

https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

[url=http://ciproo.online/]how much is cipro[/url]

[url=https://drdoxycycline.online/]doxycycline cheap australia[/url]

[url=http://xlyrica.com/]lyrica without rx[/url]

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican drugstore online

mexican drugstore online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] mexican pharmacy

http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies

[url=https://bacclofen.online/]medication baclofen 10 mg[/url]

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

[url=https://ifinasteride.com/]cheapest propecia uk[/url]

reputable mexican pharmacies online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexican drugstore online

mexican drugstore online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican pharmaceuticals online

[url=http://glucophage.online/]glucophage lowest price[/url]

mexican pharmaceuticals online: medicine in mexico pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican rx online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

[url=http://flomaxms.online/]flomax 23497[/url]

I used to be recommended this website by my cousin. I am not positive whether this

post is written via him as no one else know such specific approximately my problem.

You are amazing! Thanks!

mexican mail order pharmacies: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medication from mexico pharmacy[/url] mexico pharmacy

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying from online mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican pharmaceuticals online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican mail order pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican mail order pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican rx online

buying prescription drugs in mexico [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa[/url] mexican drugstore online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican rx online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: best online pharmacies in mexico – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

[url=https://dezithromax.online/]can you purchase zithromax[/url]

[url=http://eflomax.com/]flomax 0.4 mg capsule[/url]

medication from mexico pharmacy: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

[url=https://doxycyclineo.com/]best price for doxycycline 100 mg[/url]

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

[url=http://aaccutane.com/]buy accutane 20mg[/url]

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican rx online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

[url=http://diflucanr.com/]where can you buy diflucan over the counter[/url]

purple pharmacy mexico price list: medicine in mexico pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

mexican rx online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican pharmaceuticals online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican drugstore online

mexican drugstore online: best online pharmacies in mexico – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

[url=https://doxycyclineo.online/]doxycycline 300 mg cost[/url]

[url=http://finasterideff.com/]how to get propecia in canada[/url]

[url=http://accutaneo.com/]accutane cost in south africa[/url]

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican rx online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medication from mexico pharmacy: buying from online mexican pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]best online pharmacies in mexico[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican mail order pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

[url=https://ciproo.online/]cipro prescription[/url]

medicine in mexico pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican rx online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican rx online

mexican rx online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

[url=https://baclofenx.com/]baclofen 20 mg coupon[/url]

buying propecia without prescription [url=https://propeciabestprice.pro/#]buying generic propecia without dr prescription[/url] cost cheap propecia price

prednisone price australia: brand prednisone – buy prednisone online no script

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# does tamoxifen cause menopause

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

[url=http://lasixav.online/]buy furosemide 20 mg online[/url]

[url=https://avermox.online/]vermox australia[/url]

order cheap propecia no prescription [url=https://propeciabestprice.pro/#]get generic propecia tablets[/url] how cЙ‘n i get cheap propecia pills

how to buy prednisone: 400 mg prednisone – generic prednisone cost

http://cytotecbestprice.pro/# Abortion pills online

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen lawsuit

prednisone 30 mg [url=https://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]buy prednisone 40 mg[/url] prednisone 2 mg

cost of generic propecia pills: get generic propecia pill – order cheap propecia pill

https://prednisonebestprice.pro/# medicine prednisone 10mg

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen pill

[url=http://eflomax.com/]flomax erectile dysfunction[/url]

[url=http://albuterolp.online/]how to get albuterol[/url]

[url=http://avermox.online/]vermox buy online uk[/url]

prednisone without rx [url=https://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]buying prednisone mexico[/url] prednisone 20mg online without prescription

where to get zithromax over the counter: zithromax generic price – can you buy zithromax online

how to lose weight on tamoxifen: should i take tamoxifen – tamoxifen endometriosis

[url=http://flomaxms.com/]buy flomax otc[/url]

tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention: nolvadex 20mg – tamoxifen benefits

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec online

[url=http://diflucand.online/]diflucan buy without prescription[/url]

order generic propecia without rx: buy cheap propecia tablets – propecia brand name

[url=https://okmodafinil.com/]provigil australia[/url]

[url=https://diflucand.com/]diflucan buy online usa[/url]

tamoxifen vs clomid: tamoxifen for gynecomastia reviews – does tamoxifen cause menopause

[url=https://accutaneiso.online/]accutane online[/url]

[url=http://ibaclofen.com/]baclofen cost uk[/url]

zithromax 500mg: generic zithromax azithromycin – zithromax drug

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# does tamoxifen cause menopause

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]buy tretinoin gel[/url]

zithromax capsules: zithromax prescription online – zithromax capsules

[url=https://vermoxin.online/]buy vermox cheap[/url]

[url=http://eflomax.online/]where can i get cheap flomax[/url]

[url=http://amoxicillinbact.com/]amoxicillin uk price[/url]

[url=https://lasixtbs.com/]buy lasix online usa[/url]

buy cytotec over the counter: cytotec pills buy online – cytotec online

[url=https://avermox.online/]vermox pharmacy canada[/url]

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]where can i buy tretinoin[/url]

[url=https://ciproffl.online/]ciprofloxacin 750 tablet[/url]

[url=https://accutaneiso.com/]accutane for sale uk[/url]

[url=https://acyclovirmc.com/]acyclovir cream 10g[/url]

[url=https://flomaxms.com/]noroxin pills[/url]

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

farmacia online: Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita – farmacia online senza ricetta

[url=http://itretinoin.online/]tretinoin 20 mg capsule[/url]

[url=http://tretinoineff.com/]buy generic retin a cream[/url]

viagra ordine telefonico: viagra online – miglior sito per comprare viagra online

migliori farmacie online 2024: kamagra oral jelly – Farmacie online sicure

https://cialisgenerico.life/# Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

[url=https://effexor.directory/]can i buy effexor online[/url]

Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: kamagra gel – п»їFarmacia online migliore

[url=http://xmodafinil.com/]provigil best price[/url]

migliori farmacie online 2024: kamagra – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

Farmacia online miglior prezzo: Farmacia online migliore – farmacia online senza ricetta

[url=http://vermox.company/]vermox medication[/url]

viagra ordine telefonico: viagra farmacia – esiste il viagra generico in farmacia

http://farmait.store/# farmacia online

[url=http://accutaneiso.com/]buy accutane canada[/url]

[url=https://adfinasterid.online/]propecia pills[/url]

п»їFarmacia online migliore: Avanafil a cosa serve – Farmacie online sicure

[url=https://baclofem.com/]baclofen 10mg tablet[/url]

migliori farmacie online 2024: kamagra gold – farmacia online

[url=https://declomid.online/]buy 150 mg clomid[/url]

farmacia online: Farmacia online piu conveniente – Farmacia online miglior prezzo

https://farmait.store/# farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

[url=http://strattera.company/]generic strattera india[/url]

generic cialis mexico: Buy Cialis online – order cialis no prescription

http://tadalafil.auction/# cialis daily price

cialis viagra australia: Buy Tadalafil 20mg – generic cialis priligy australia

http://tadalafil.auction/# cialis 20 mg dosage

viagra cost [url=http://sildenafil.llc/#]Cheap Viagra 100mg[/url] п»їover the counter viagra

http://sildenafil.llc/# viagra online

cialis vs viagra canadian pharmacy: Buy Cialis online – cialis цена

lowest price generic cialis: Generic Tadalafil 20mg price – buy 10 mg cialis

http://tadalafil.auction/# generic cialis usps priority mail

cheapest ed treatment: Cheapest online ED treatment – erectile dysfunction pills online

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# india online pharmacy

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# erectile dysfunction meds online

buy ed medication

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacy online

erectile dysfunction drugs online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico pharmacy win – best online pharmacies in mexico

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacies safe

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# mail order pharmacy india

ed online prescription

cheap ed pills: Best ED pills non prescription – ed meds on line

medicine in mexico pharmacies: Best online Mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# Online medicine home delivery

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: Mexico pharmacy online – mexican rx online

online ed meds: Best ED pills non prescription – buy ed pills

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# low cost ed pills

online ed medications: where can i get ed pills – order ed pills

cheapest online pharmacy india: Indian pharmacy international shipping – buy medicines online in india

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# reputable indian pharmacies

pharmacy website india: Online medicine order – indian pharmacy online

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# online ed treatments

best india pharmacy: Indian pharmacy international shipping – reputable indian online pharmacy

ed treatment online: Cheap ED pills online – buy ed meds online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# online erectile dysfunction

low cost ed meds online: Cheap ED pills online – buying ed pills online

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indianpharmacy com

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: Medicines Mexico – mexican drugstore online

ed medicine online: Best ED meds online – ed rx online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: reputable mexican pharmacies online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican rx online

mexican drugstore online: Medicines Mexico – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico pharmacy win – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buy cytotec in usa: cytotec best price – Cytotec 200mcg price

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril prices

lasix medication

https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen citrate pct

tamoxifen generic: buy tamoxifen citrate – hysterectomy after breast cancer tamoxifen

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen moa

lasix dosage

http://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen hip pain

furosemide [url=http://furosemide.win/#]cheap lasix[/url] lasix 20 mg

cytotec pills buy online: cytotec best price – buy cytotec over the counter

buy cytotec over the counter http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril price in india

buy lasix online

https://tamoxifen.bid/# п»їdcis tamoxifen

buy cytotec pills online cheap https://tamoxifen.bid/# natural alternatives to tamoxifen

lasix

hysterectomy after breast cancer tamoxifen [url=https://tamoxifen.bid/#]buy tamoxifen online[/url] natural alternatives to tamoxifen

lipitor 20 mg where to buy: buy lipitor 20mg – lipitor generic india

https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec pills

buy cytotec over the counter http://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec

furosemida 40 mg

tamoxifen adverse effects: buy tamoxifen online – nolvadex steroids

lasix online: buy furosemide – lasix tablet

buy misoprostol over the counter https://lipitor.guru/# buy lipitor 10 mg

furosemide 100mg

lisinopril 5 mg buy: buy lisinopril – lisinopril 20 mg mexico

http://furosemide.win/# lasix uses

buy cytotec online: cytotec best price – buy cytotec over the counter

cytotec buy online usa https://cytotec.pro/# order cytotec online

furosemida

cheap lipitor 20 mg: buy lipitor 20mg – п»їlipitor price comparison

lasix: cheap lasix – lasix pills

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 10 mg order online

buy lasix online

brand name lipitor: cheapest ace inhibitor – lipitor brand

cytotec online: Abortion pills online – buy cytotec pills

buy cytotec pills https://furosemide.win/# furosemide 40mg

lasix generic name

where can i buy nolvadex: nolvadex pct – tamoxifen and depression

buy lipitor from canada: average cost of generic lipitor – lipitor prices australia

buy cytotec https://lipitor.guru/# lipitor 40mg

lasix uses

top online pharmacy india [url=http://easyrxindia.com/#]reputable indian pharmacies[/url] Online medicine home delivery

http://mexstarpharma.com/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://mexstarpharma.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

indianpharmacy com [url=http://easyrxindia.com/#]buy prescription drugs from india[/url] indian pharmacies safe

http://mexstarpharma.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

canadian neighbor pharmacy: canadian online drugs – canadian pharmacy sarasota

buying from online mexican pharmacy: reputable mexican pharmacies online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://mexstarpharma.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican drugstore online [url=https://mexstarpharma.com/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: cheapest online pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

https://easyrxcanada.com/# best rated canadian pharmacy

http://mexstarpharma.com/# mexican drugstore online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican rx online

mexican mail order pharmacies: buying from online mexican pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://easyrxcanada.online/# canadian pharmacy online

canadian family pharmacy: canadian pharmacy near me – canadian pharmacy oxycodone

https://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian pharmacy checker

en cok kazandiran slot siteleri: slot oyunlar? siteleri – guvenilir slot siteleri 2024

en guvenilir slot siteleri: deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri – deneme bonusu veren siteler

http://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

canl? slot siteleri: en iyi slot siteler – canl? slot siteleri

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт смартфона

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri: canl? slot siteleri – slot casino siteleri

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri: en iyi slot siteler – en cok kazandiran slot siteleri

https://sweetbonanza.network/# sweet bonanza oyna

2024 en iyi slot siteleri: bonus veren slot siteleri – 2024 en iyi slot siteleri

priligy pills Although it has antioxidant properties, grape seed has not been shown to treat or prevent cancer

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# bonus veren siteler

en yeni slot siteleri: en iyi slot siteler – deneme bonusu veren siteler

ремонт apple watch

http://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

2024 en iyi slot siteleri: slot casino siteleri – 2024 en iyi slot siteleri

pin up казино: пинап казино – пин ап

http://1xbet.contact/# 1xbet

1хбет зеркало: 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия – 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планетов в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт планшетов apple в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту радиоуправляемых устройства – квадрокоптеры, дроны, беспилостники в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт квадрокоптеров в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

pin up: пин ап зеркало – пин ап казино

1xbet официальный сайт: 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня – 1xbet

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервис центр в екатеринбурге

пин ап казино вход [url=https://pin-up.diy/#]пин ап вход[/url] pin up

http://pin-up.diy/# пин ап казино

1win официальный сайт: 1вин сайт – 1win зеркало

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи ремонт

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт ноутбуков смартфонов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

pin up казино: пин ап казино вход – пинап казино

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:сервис центры бытовой техники петербург

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://vavada.auction/# vavada

1хбет официальный сайт: 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия – зеркало 1хбет

1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня: 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия – зеркало 1хбет

http://pin-up.diy/# пин ап казино вход

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи новосибирск

ремонт телефонов москва

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту источников бесперебойного питания.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт ибп цена

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

1хбет: 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия – 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня

ремонт плазменных телевизоров замена экрана цена

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервис центр в барнауле

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи услуги

https://onlineph24.com/# 24 hour drug store near me

ddavp online pharmacy

online pharmacy modafinil: pharmacy generic viagra – levitra pharmacy prices

https://easydrugrx.com/# on line pharmacy

correct rx pharmacy services

no prior prescription required pharmacy: clozapine pharmacy registration – sildenafil online pharmacy

ремонт цифровых фотоаппаратов в москве

https://pharm24on.com/# Chloromycetin

vermox online pharmacy [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]cheapest pharmacy[/url] Enalapril

https://pharm24on.com/# 1st pharmacy net cialis acheter sur internet

cialis pharmacy prices

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт бытовой техники в екб

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту варочных панелей и индукционных плит.

Мы предлагаем: срочный ремонт варочной панели

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

people’s pharmacy: acyclovir cream pharmacy – compound pharmacy online

https://easydrugrx.com/# illegal online pharmacy

mexican pharmacy percocet [url=https://onlineph24.com/#]tijuana pharmacy cialis[/url] tylenol scholarship pharmacy

va pharmacy online: online pharmacy college – Mobic

Зеркало сайта доступно для постоянного использования на https://888starz.today

https://drstore24.com/# Detrol

best pharmacy store

https://drstore24.com/# online pharmacy viagra australia

tamiflu online pharmacy [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]provigil indian pharmacy[/url] best drug store foundation

zovirax cream online pharmacy: online pharmacy doxycycline – periactin uk pharmacy

online pharmacy birth control pills: doxycycline people’s pharmacy – lexapro pharmacy assistance

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в челябинске

https://onlineph24.com/# pentasa online pharmacy

international pharmacy no prescription [url=https://drstore24.com/#]triamcinolone cream online pharmacy[/url] methylphenidate online pharmacy

pharmacy store window: viagra uk online pharmacy – clozaril pharmacy registration

online pharmacy cialis uk: publix pharmacy wellbutrin – flonase online pharmacy

https://onlineph24.com/# target pharmacy clindamycin

atorvastatin target pharmacy [url=https://drstore24.com/#]Aristocort[/url] legit online pharmacy viagra

Comments are closed.