27/09/2021 par Elie Saad

“Is a triangle space able to integrate the club of public squares? If so, why do we even call it a square and not just a space or why don’t we call every space by its geometrical shape? Maybe this is why the Riad al-Solh Square isn’t really a living public space, maybe the real reason is its triangular shape” – Elie Saad

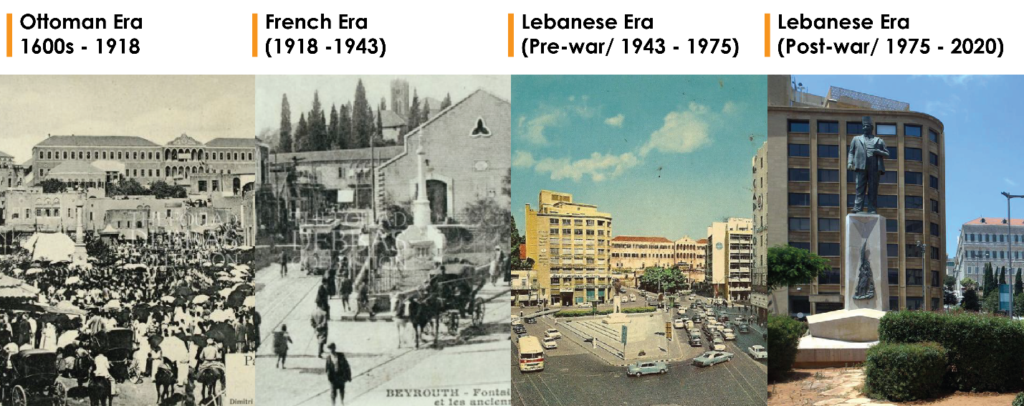

Currently known as a place of major protests, especially due to the 2019 uprising, the Riad al-Solh Square is nevertheless one of the oldest squares and public spaces in Beirut dating back to the Beirut intra-muros era. The square evolved with the city that wrapped itself around it making it the geographical, political and economic center of the Lebanese capital. Its history and evolution are briefly examined in this article.

Ottoman Era (1800s – 1920)

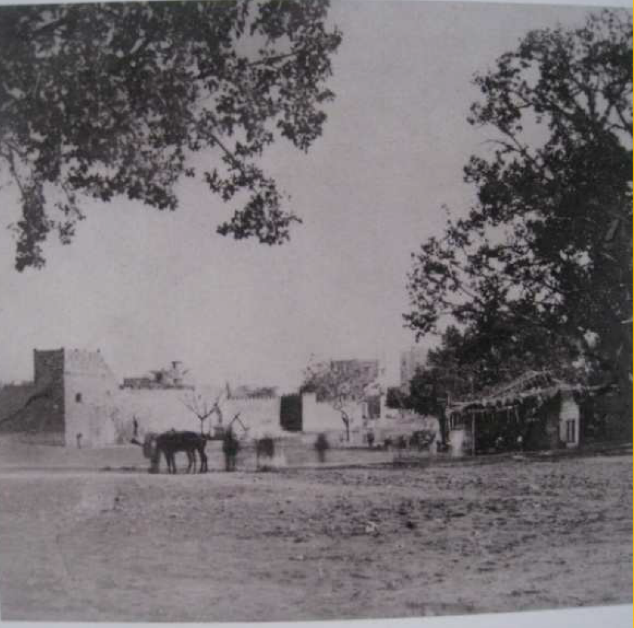

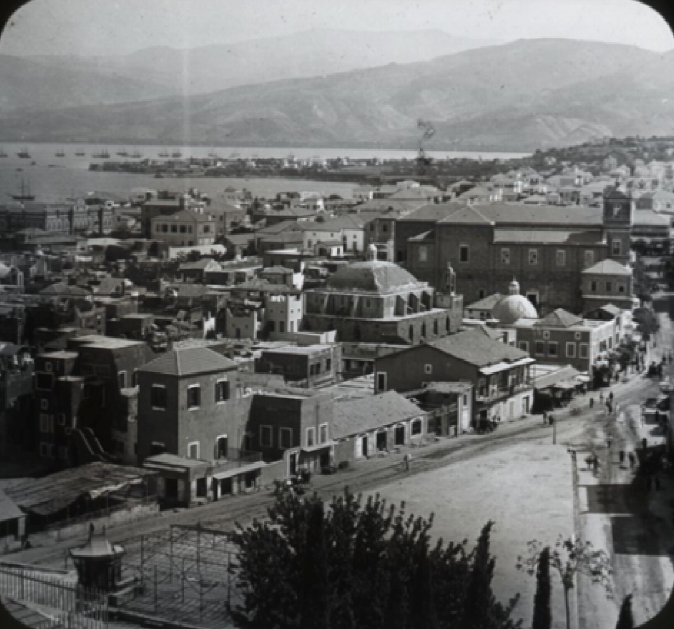

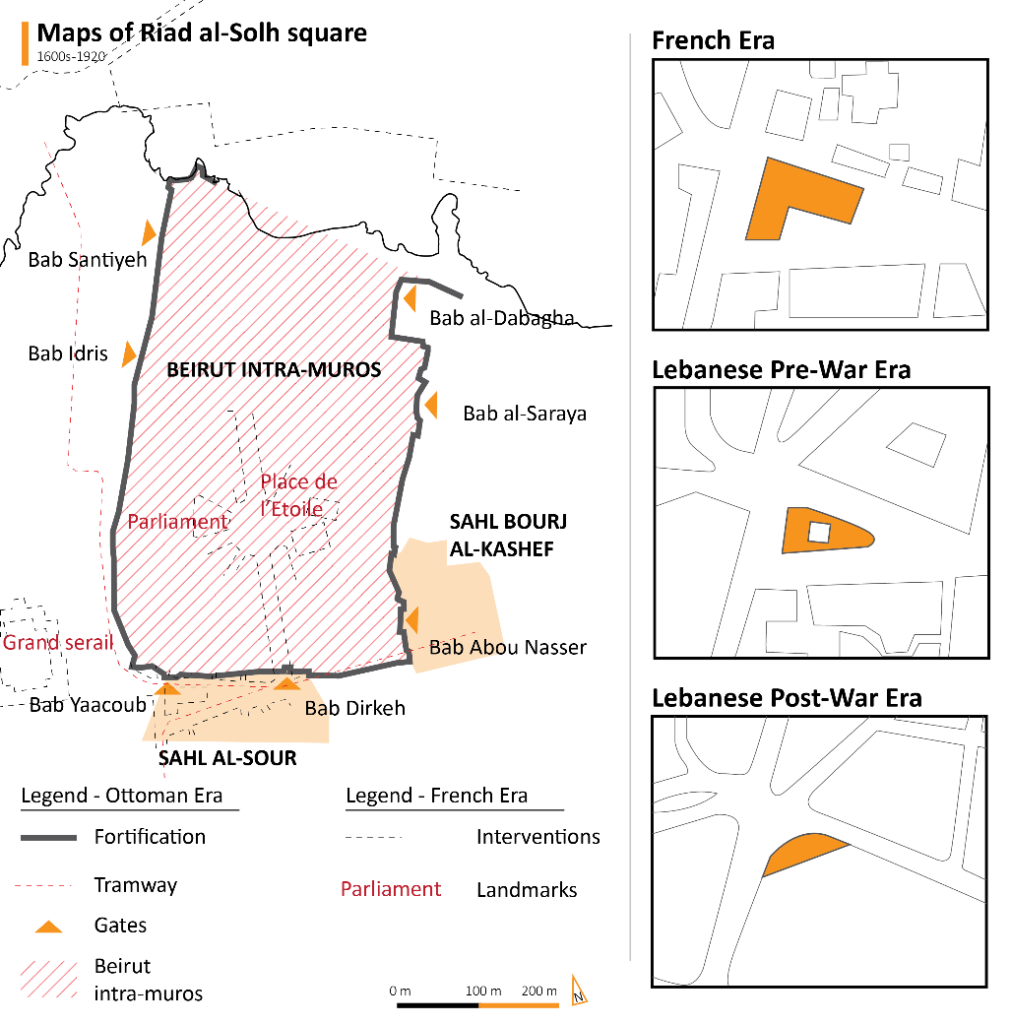

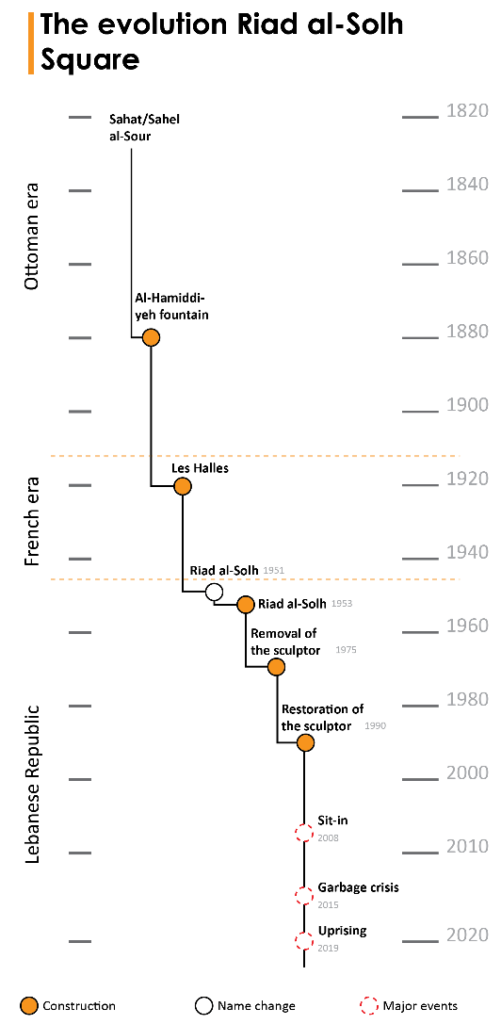

During the Ottoman era and before the expansion of the mid-19th century, Beirut was considered a small city on the eastern Mediterranean coastline. The city had a defensive wall to protect it from enemy invasion; the wall had seven doors that enabled the creation of connection points with the outside world. On the eastern side of the wall, a maydan (square) developed near the door called Bab al-Serail, later to be named Martyr’s square (for further information you can read the previous publication on Observatoire Patrimoine d’Orient, Park to Parking: the socio-spatial evolution of Beirut’s martyrs square). On the southern side of the wall one of the two doors, Bab al-Dirkeh, enabled the creation of a second, smaller maydan outside the city walls. The maydan, also called Sah at al-Sour (Sour meaning defensive wall in Arabic), will later evolve to become the Riad al-Soleh Square.

Source: Nadine Khayat from Debbas Collection

The Ottoman Tanzimat* started a movement of reform and modernization in the city of Beirut at different levels, notably pertaining to the urban and architectural dimensions. With the creation of a new Ottoman architectural and urban style and the slow development of Beirut extra-muros, the two maydans started developing in an urban perspective. After the creation of the Petit Serail and the Hamidiyeh Garden in what is now known as Martyr’s square, a similar function was planned for the Sahat al-Sour. The municipality of Beirut started executing the project by tearing down workers’ cafés but, at a later stage, the planning of the sahat was modified twice and, eventually, a tall marble fountain was erected in the sahat. The fountain was named al-Hamidiyeh in honor of the Ottoman sultan Abdelhamid II. The square flourished as a main passage point on the Beirut – Damascus route which, at the time, passed through the area. This transportation function was also accentuated by the path of the tramway of Beirut that passed through the square. During the late Ottoman period, several urban projects were initiated or planned by the Ottoman authorities and later stalled due to the political situation and the Great War.

French Mandate (1920 – 1943)

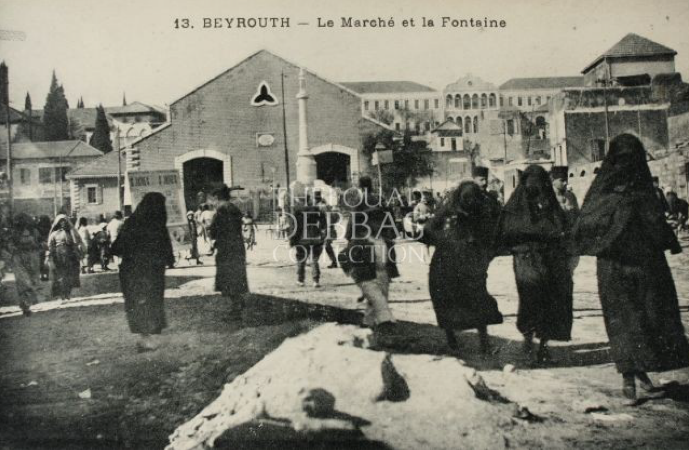

With the French mandate imposed on Lebanon, the authorities of the mandate wanted to finish the already stalled urban projects to establish a sense of control and the “getting things done”. The majority of the plans established by the Ottomans were kept and executed. In addition, the French authorities created the “Place de l’Etoile”, which was directly connected to the square through a road. It should have been also connected to the Martyr’s square, but the project was halted to avoid destroying two Orthodox churches. New plans of urban projects were drawn. Regarding the Sahat al-Sour, its characteristics remain largely unchanged: the French mandate constructed the “Les Halles” market in the square, which enabled it to gain importance as an economic hub.

Source: Nadine Khayat from Debbas Collection

Source: Nadine Khayat from Debbas Collection

Lebanese Republic, Pre-war (1943 – 1975)

With French influence on the country and the general governmental structure in terms of laws and culture, no major modifications were noted in the planning of the public spaces in general and in the Sahat al-Sour specifically. The square slowly lost its role as an economic hub and became more of a vehicular transportation node with the increased reliance on the car in Beirut. The square remained the Sahat al-Sour until 1951 when it was renamed after the Lebanese Prime Minister Riad al-Solh*, assassinated in Amman in the same year. Later on, in 1957, the Hamidiyeh fountain was moved to the Sanayeh garden and was replaced by the statue of the former prime minister, sculpted by the Italian sculptor Marino Mazzacurati.

With the economic boom and the flourishing banking sector in Lebanon at the time, the buildings surrounding the square saw major transformation without any changes in the cadastral boundaries of the square itself. Several buildings were erected in the 1950s or 1960s, the Capitole and the Pan American buildings being the most notable ones and still standing today. The road to the northern end of the square, which was also named Riad al-Solh Street, became the banking street of Lebanon, and the majority of the banks’ headquarters established there.

source: Lebanon in a picture

source: Lebanon in a picture

Lebanese Republic, Post-war (1975 – 2021)

During the Lebanese Civil War, the statue of the former prime minister was removed to be protected while the area nearby saw fierce fighting that led to great destruction of the urban environment in Beirut. After the civil war, the square was reconstructed back to its original triangular footprint and the restored statue of Riad al-Solh regained its place within its boundaries. However, on the social level, the square became a traffic island with no social life. This transformation was due to several reasons, one of them was the new image of the public and commercial spaces in the post-war Beirut with the high-end retails aimed mainly to attract tourists and investors from the Gulf countries. On the southern side, the numerous residential and commercial buildings (picture 6) were destroyed by Solidere* to build a parking which is currently an excavation site. The isolation of the square was furthermore accentuated by the newly built United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN-ESCWA) buildings and the security measures surrounding it. The combination of these factors made the square a ghost space, in terms of social life, only revived by the protests and demonstrations that took place there from time to time.

In the 2000s and until the 2019 uprising, the square saw several sit-in protests and demonstrations of several parties mainly due to the proximity of the Grand Serail, the headquarters of the Lebanese government. The most notable of these demonstrations in terms of scale were the protests during the October 2019 uprising which occupied the square for several weeks and led to its closure. During this period, the square was buzzing with tents of several political and social groups, some of them having debates on the political situation and others preparing and distributing food for the protesters. The Lebanese authorities, on the other hand, barricaded the square with a 2.5-meter-high concrete wall topped with barbed wires to enclose the protests and protect the Grand Serail and the parliament. The strategic location of the square gave it a direct access via two separate roads to these two major political buildings. The “fall” of the square when the Lebanese authorities “recaptured it” sent an important political signal to the opposing groups.

In this context, the following question might be asked: with the uncertainties, division, and violence that Lebanon is currently witnessing, isn’t it ironic that a square ending with “al-Solh” (“reconciliation” in English) became a symbol of division and confrontation among Lebanese?

Tanzimat:

Figure 11: Walls constructed to block the protests, 2020, Unknown

The Tanzimat are a series of changes to the Ottoman laws and rules erected in the 19th century with the aim of modernizing the Ottoman empire by removing the millet system and unifying the Empire’s citizens under the rule of a modern state.

Riad al-Solh:

Riad al-Solh was the first Lebanese prime minister after the independence in 1943 and one of the founders of modern-day Lebanon. He was born in Sidon, Southern Lebanon, and worked in the political since the Ottoman period. Imprisoned by the French authorities in 1943 with the President with whom he managed to create the “Mithak al-Watani” (national consensus) that governs the politico-religious distribution of power in Lebanon till this day. He remained Prime Minister till 1945 and was assassinated in 1951 in Amman, Jordan.

Solidere:

A company was established in 1994 with a special public-private partnership statue and named “SOLIDERE” “Société Libanaise pour le Développement et la Reconstruction du Centre-ville de Beyrouth” (English: The Lebanese Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut Central District). The company created the master plan and building regulations upon which the center reconstruction was based on. In these plans, a large portion of the old and traditional buildings of Beirut were destroyed to create space for more high-end modern buildings to attract investors, in the hope of creating Beirut an international and regional business city.

References:

– Jean-Luc Arnaud, ed. Beyrouth, Grand Beyrouth, Beyrouth : Presses de l’Ifpo, 1996.

– May Davie, « Au prisme de l’altérité, les orthodoxes de Beyrouth au début du XIXè siècle », Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée, 107-110, 2005, pp. 161-182.

– Nadine Hindi, « Narrating Beirut Public Spaces Westernization », Méditerranée, 131, 2020, 15 février 2021, http://journals.openedition.org/mediterranee/11486.

– Nadine Hindi, On the making of public spaces in Beirut, Barcelone : Universitat de Barcelona, 2015.

– Helmut Ruppert, Beyrouth, une ville d’Orient marquée par l’Occident, Beyrouth : Presses de l’Ifpo, 1999.

– Samir Kassir, Beirut, Berkeley : University of California Press, 2010.