10/06/2021 by Nassima Chahboun

The city of Taza lies at the saddle between the Atlas and the Rif mountains, in the north of Morocco. The medina (from the Arabic word madinah, meaning “city”) is the historic part that dates back to the pre-Islamic era and represents an urban and architectural palimpsest illustrating the succession of several Islamic dynasties.[1]

Due to its strategic location at the crossroads between the east and the west, Taza played a key role in the geopolitical transformations of the Moroccan kingdom until the start of the French protectorate.[2] After independence, the epic of this city came to its end and many monuments in the medina were partially or completely lost.

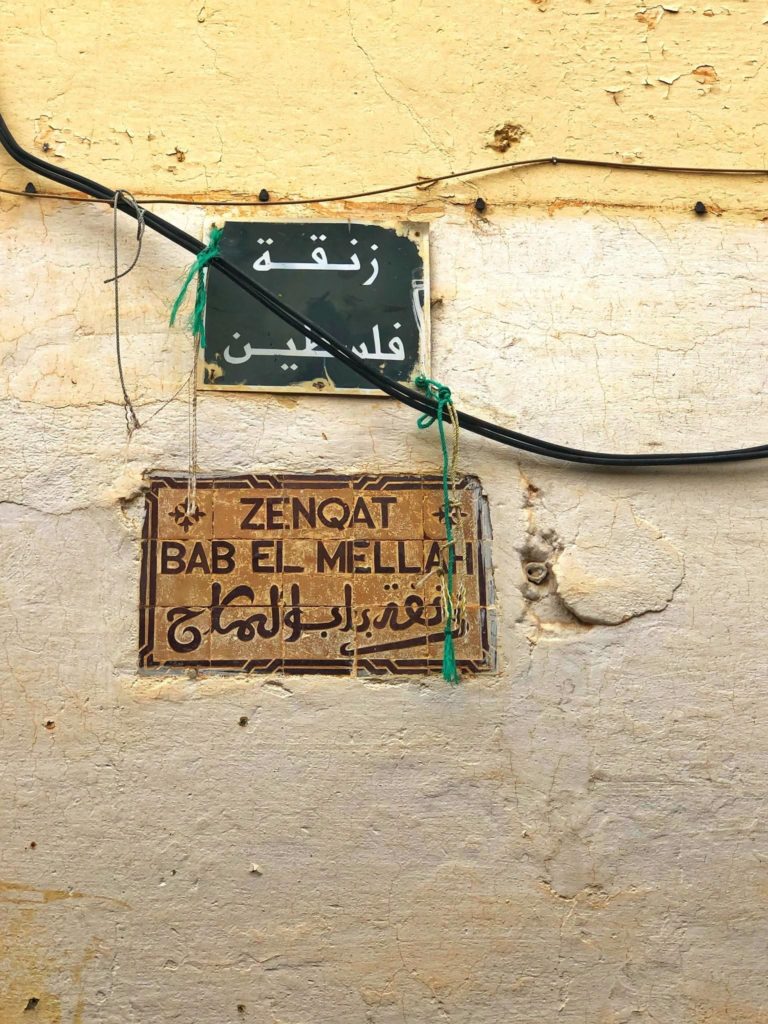

Today, walking through the narrow streets of the medina of Taza resembles walking over a shrouded history, and passing by hundreds of stories hidden behind the faded walls and the ever-closed doors. However, if the buildings have lost their ability to depict the local culture and the spirit of the place, the words that have been written about the city a few centuries ago are still alive and still able to convey a genuine image of its glorious past. Today, the genius locus of the medina of Taza is not found in the physical space, but rather in narratives and poetry.

In this article, the medina will be presented through a confrontation between its tangible and intangible layers: the built space as well as examples of the remaining poetry and travel narratives from three key periods in its history, namely the Almohad dynasty, the Marinid dynasty and the pre-Protectorate Alaouite dynasty.

Amidst the pale stones: the physical space

The medina, also called “Upper Taza”, is located at the top of a hill in the southwest of the city. It is a compact urban fabric surrounded by a 3-kilometre-long rampart with several gates ensuring the direct connection with its periphery, such as cemeteries and agricultural fields. Given the rugged topography, the medina is connected to the modern city by a 250-metre-long stairway bordering the defensive walls in a slightly sloping manner in harmony with the natural and the built environments.

This synergy between the medina’s location and the mountainous landscape in the background results in an enchanting scenery. Yet, the buildings’ incongruity in terms of typology, proportion, materials and colours is noticeable. In fact, over 60% of the medina’s urban fabric is composed of neo-traditional extensions, built during the French Protectorate and after Morocco gained its independence. These extensions have overlapped with the original traditional fabric, and in some parts, have altered it.[3]

Another factor is the decades-long absence of a holistic conservation strategy for the medina of Taza, which led to drastic changes in many built areas and to the deterioration of many monuments. According to a census conducted in 2000, only 13% of the buildings made of traditional fabric are in a good state, 10% are completely in ruins and 23% are closed and inaccessible.[4]

The ramparts are among the few remaining historical monuments. These were built during the Almohad dynasty and strengthened by the Marinids and the Saadians.[5] Among the other historical monuments that are still standing today are the Bastion fortress built by the Saadians,[6] Al Mechouar space that dates back to the early Alaouite period,[7] and the Great Mosque (Jamaa Lakbir), which is the only monument that is fully preserved and still operating. In fact, this mosque, built during the 12th century by the Almohads and expanded by the Marinids in the late 13th century, is one of the oldest surviving examples of Almohad architecture.[8]

Taza remained an outstanding example of civilization and architectural ingenuity until the end of the 19th century

Through the shimmering words: The memory of the place

Taza during the Almohad and Marinid dynasties

The Great Mosque also represents an invitation to explore local history. In the main prayer hall, that dates back to Almohad period, an enormous bronze chandelier tells a fragment of the story of the Mosque and the medina, through a poetic inscription carved on it: [9]

يا ناظرا في جمالي حقق النظرا … ومتع الطرف في حسني الذي بهرا

أنا الثريا التي تازا بي افتخرت …. على البلاد فما مثلي الزمان يـــرى

أفرغت في قالب الحسن البديع كما … شاء الأمير أبو يعقوب إذ أمـــرا

في مسجد جامع للناس أبدعه … ملك أقام بعون الله منتصــــــــــــرا

له اعتناء بدين الله يظــــهره… يرجو به في جنان الخلد ما ادخـــــــرا

في عام أربعة تسعون تتبعها … ست المئين من الأعوام قد سطـــــرا

تاريخ هذي الثريا والدعا لأبي… يعقوب بالنصر دأبا يصحب الظفـرا

(Watch my beauty, enjoy my dazzling grace

I am the unique chandelier that made Taza proud

I was ordered by prince Abu Ya’qub,

modelled in a mould of beauty,

and put in a mosque that was conceived by a great king,

who has always served the religion,

694 [HA] is the date of conception of this chandelier,

Prayers for my father Ya’qub, and wishes of victory)

At first, one might assume that the prince “Abu Ya’qub” who ordered the chandelier is the Almohad Sultan “Abu Ya`qub Yusuf Ibn Abdul-Mu’min”, given that the Mosque was built during this specific time period and that the architecture of the prayer hall is purely Almohad in terms of configuration, proportions and details (the naves that are perpendicular to the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba shrine in Mecca, the lack of ornaments of the square pillars, the minaret and the walls). Yet, the inscribed conception date (694 AH) refers to the Marinid period, and hence, the prince in question is “Abu Ya’qub Yusuf an-Nasr”.

This poem is a key element to understanding the mosque’s evolution, as it provides accurate information that architecture could not convey, but most importantly, it depicts the importance of Taza during the Marinid period. First, through its mere existence, given the fact that decorating a regular object with unique poetry was not recurrent; carvings often encompassed Quranic verses and general poems and quotes. Second, through its content, as it shows that the chandelier is of an unprecedented elegance and was exclusively conceived for this mosque.

Another intriguing written account that confirms the importance of Taza for the Marinids and that provides further details about the city is the Description of Africa by Leo Africanus (Hasan Al-Wazzan) at the beginning of the 16th century. According to Al-Wazzan, Taza was the third city in the kingdom in terms of status and civilization, and it was the official summer residence of the Marinid Sultans. For this reason, the medina encompassed a multitude of important services: several madrasas, fonduks (hotels), baths, and the Great Mosque, bigger than the mosque of Fez, which was the capital at the time. The population was also known to be wealthy and educated. Al-Wazzan also sheds light on a component of the city that has now disappeared: an important Jewish community who inhabited nearly 500 houses.[10]

The Andalusian historian Ibn Al-Khatib had also described the Marinid Taza as“a land of resistance and truth, of wealth and prosperity, of sweet water and fresh air, and an embodiment of God’s gifts and wonders”.[11] Yet, the importance of Taza did not start with the Marinids. In Al-Bayan al-Mughrib (also known in English as Book of the Amazing Story of the History of the Kings of al-Andalus and Maghreb), written around 1312, the Marrakesh-born historian Ibn Idhari outlines the status of this city: “Once settled in Taza, Abu Yahya, the Marinid prince, ordered to beat the drums and raise the flags. Tribe delegations from all over the country came to present their congratulations. These celebrations were never organized before, although several cities and regions have been taken”.[12]

In fact, Taza thrived several decades earlier. According to the anonymous author of Al Istibsar fi Ajaibi Al Amsar written during the Almohad period, the medina was founded around 1172 and built as a fortress with significant fortifications, described by the author as a “magnificent and everlasting wall, made of stone and lime”. When the fortress was built, the region was already inhabited. The author also describes the harmony between the natural and the built environments, through the example of the pouring water that stems from the mountains and flows through the city streets to the surrounding fields.[13]

Today, a successful restoration effort of the medina of Taza would be almost impossible due to the severe deterioration that has led to the complete collapse of many important buildings and because reconstruction would falsify history if based on conjecture despite the availability of detailed documentation

Taza during the Alaouite Dynasty

Taza remained an outstanding example of civilization and architectural ingenuity until the end of the 19th century.

In the 18th century, Al-Sharqi Al-Ishaqi, the minister of the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Ismail, visited Taza during his journey to Al Hijaz with the de facto prime minister Khnata Bent Bakkar, the sultan’s wife. Al Ishaqi describes the city as an impregnable fortress, a charming illustration of civilization, and a living memory of Marinid art. The Great Mosque, according to him, is one of the greatest mosques in the country in terms of size, solidity and ornament, and its maqsura (an enclosure in a mosque typically reserved for a Muslim ruler) has a unique gypsum art decoration.[14]

Al-Ishaqi also describes a “marvellous” Marinid madrasa juxtaposing the Great Mosque (which is nowadays in ruins). The following poetry inscribed on its main gate outlines its uniqueness in terms of architecture[15] and the importance given to it by the Marinid princes:

لعمرك ما مثلي بشرق ومغرب يفوق المباني حسن منظري الحسن

بنانـــي لدرس العلم مبتغيا بــــــــه ثوابــــــــــا مـــن الله الأميــــــــر أبـــــــــي الحسن

(I swear, no building in the world is equivalent to me,

my beauty exceeds every building,

I was built by the prince Abu Al Hasan,

for the sake of knowledge and of God’s mercy)

In the early 1800s, the Spanish officer Domingo Badia y Leblich, also known as Ali Bey, travelled to Morocco as part of an expedition to Africa and Asia. In his book Voyages of Ali Bey in Africa and Asia during the Years 1803–1807, he describes Taza as the prettiest of all the cities he has seen in the Empire of Morocco, and states that “it is the only one where one sees no ruins. Its streets are beautiful, the houses pretty and painted. The main mosque is very large, well-built and has a beautiful vestibule. There are several well-stocked markets, a great number of shops and very beautiful gardens”. Ali Bey also concludes: “These advantages make me prefer the city of Taza to all the other cities of the empire, even to Fez, the capital”.[16]

Reviving the memory of the place: Storytelling within the built space

Today, a successful restoration effort of the medina of Taza would be almost impossible due to the severe deterioration that has led to the complete collapse of many important buildings and because reconstruction would falsify history if based on conjecture despite the availability of detailed documentation. One could argue that it would be a mere reproduction of the shell, and not a restitution of the city’s spirit.

Yet, reviving this medina is possible through putting words where stones can no longer be placed. Storytelling, supported by new technologies, can be a powerful tool to recall the past while preserving the city’s authenticity, and to shape a meaningful experience for the inhabitants and visitors. Possible interventions are plentiful and can be based on simple and widely available tools and methods, such as creating instructive circuits with the use of QR codes that can be incorporated into entrance plaques on buildings, to give access to articles, images or audio files that describe these buildings and areas. In the case of buildings that have completely disappeared, the QR codes can also play the role of virtual memorials. Gamification can be of tremendous value as well, to create more appealing experience;[17] mobiles games based on geo-localisation and augmented reality, for instance, are able to give a new dimension to the built space.

I believe that these synergies between the built and the written, the stories of the past and the storytellers of the present are not only possibilities, but key to reviving Taza’s spirit.

[1] Les Archives Berbères, Volume 3, Fascicule 2, Publication du Comité d’Études Berbères de Rabat, 1918.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Note de Présentation, Plan d’Aménagement de la Médina de Taza. Agence Urbaine de Taza. 2004.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Les Archives Berbères, Volume 3, Fascicule 2, Publication du Comité d’Études Berbères de Rabat, 1918.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Terrasse, Henri (1943). La grande mosquée de Taza. Paris: Les Éditions d’art et d’histoire.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Leo Africanus (circa 1550). The history and description of Africa, and of the notable things therein contained. Robert Brown. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-511-69830-9.

[11] Ibn al-Khaṭīb, Lisān Ad-Dīn (1374). Khaṭrat al-ṭayf : riḥlāt fī al-Maghrib wa-al-Andalus. Dār al-Suwaydī lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzīʻ; Bayrūt : al-Muʼassasah al-ʻArabīyah lil-Dirāsāt wa-al-Nashr, 2003.

[12] Ibn ʻIdhārī, Muḥammad (approximately 1295). Kitāb al-bayān al-mughrib fī akhbār al-Andalus wa-al-Maghrib. Bayrūt : Dār al-Thaqāfah, 1967.

[13] Anonymous author (12th century). Kitāb Al-Istibsār fī ‘Aja’ib al-Amsār. Bayrūt: Dār Sader. 1852. ISBN 978-9953138206

[14] Abi Muhammad ‘Abdul-Kadir Al-Ishaqi Al-Ishaqi (approximately 1731). The Journey of Al-Wazeer Al-Ishaqi to Hejaz 1143 H.A/1731A. [Manuscript]

[15] Ibid.

[16] Badia i Leblich, D.F.J. (1816), Travels of Ali Bey in Morocco, Tripoli, Cyprus, Egypt, Arabia, Syria, and Turkey, Between the Years 1803 and 1807, Vol. I & II, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown

[17] Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

593 comments

In today’s fast-paced world, staying informed about the latest advancements both domestically and globally is more crucial than ever. With a plethora of news outlets struggling for attention, it’s important to find a dependable source that provides not just news, but insights, and stories that matter to you. This is where [url=https://www.usatoday.com/]USAtoday.com [/url], a top online news agency in the USA, stands out. Our dedication to delivering the most current news about the USA and the world makes us a primary resource for readers who seek to stay ahead of the curve.

Subscribe for Exclusive Content: By subscribing to USAtoday.com, you gain access to exclusive content, newsletters, and updates that keep you ahead of the news cycle.

[url=https://www.usatoday.com/]USAtoday.com [/url] is not just a news website; it’s a dynamic platform that strengthens its readers through timely, accurate, and comprehensive reporting. As we navigate through an ever-changing landscape, our mission remains unwavering: to keep you informed, engaged, and connected. Subscribe to us today and become part of a community that values quality journalism and informed citizenship.

Because of the fluctuating levels of estrogen and progestin, a menopausal woman typically experiences different vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness cialis prices

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://cmqpharma.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican online pharmacy – mexican rx online

mexican drugstore online: cmq pharma mexican pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

https://canadapharmast.online/# canadian pharmacy online

top 10 pharmacies in india: best online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy paypal

http://foruspharma.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

canadian pharmacy 365 [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]canada drugs online reviews[/url] pet meds without vet prescription canada

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india [url=http://indiapharmast.com/#]indian pharmacy paypal[/url] pharmacy website india

canadian online pharmacy: onlinepharmaciescanada com – safe reliable canadian pharmacy

indian pharmacy: reputable indian online pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy

top 10 online pharmacy in india: top 10 online pharmacy in india – pharmacy website india

mexico pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

indian pharmacy paypal: buy medicines online in india – indian pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://foruspharma.com/#]mexican pharmaceuticals online[/url] mexico pharmacy

canadian pharmacy victoza [url=https://canadapharmast.online/#]safe online pharmacies in canada[/url] canadian pharmacy scam

http://indiapharmast.com/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

canadianpharmacy com: canadianpharmacyworld – prescription drugs canada buy online

canadian pharmacy online: onlinepharmaciescanada com – canada pharmacy 24h

my canadian pharmacy rx: online canadian pharmacy – canada drug pharmacy

pharmacy website india: best india pharmacy – best online pharmacy india

india pharmacy [url=http://indiapharmast.com/#]india pharmacy[/url] top 10 online pharmacy in india

top online pharmacy india: best india pharmacy – online shopping pharmacy india

http://indiapharmast.com/# indianpharmacy com

canadianpharmacyworld [url=https://canadapharmast.com/#]reliable canadian online pharmacy[/url] canadian family pharmacy

online shopping pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – pharmacy website india

onlinepharmaciescanada com: canadian mail order pharmacy – canadian world pharmacy

https://indiapharmast.com/# reputable indian online pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: top online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy paypal

best canadian pharmacy: reputable canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy uk delivery

mexican drugstore online [url=https://foruspharma.com/#]mexican mail order pharmacies[/url] mexican rx online

pharmacy website india: india pharmacy – online shopping pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy service: legit canadian pharmacy – canadianpharmacyworld

india pharmacy: reputable indian online pharmacy – online pharmacy india

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline over the counter south africa

paxlovid india: paxlovid generic – paxlovid for sale

buy clomid: get cheap clomid without rx – can i buy generic clomid without prescription

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid pill

amoxicillin 500mg buy online canada [url=http://amoxildelivery.pro/#]where to buy amoxicillin 500mg without prescription[/url] amoxicillin 500mg prescription

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid pharmacy

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# buy generic clomid pill

clomid pills [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]can you get generic clomid online[/url] can i purchase cheap clomid no prescription

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# buy amoxicillin online mexico

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin medicine

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# where to buy doxycycline over the counter

cipro for sale [url=http://ciprodelivery.pro/#]ciprofloxacin generic price[/url] п»їcipro generic

how can i get clomid no prescription: buy clomid pills – clomid without a prescription

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# buy paxlovid online

can i get generic clomid without rx [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]where to get clomid now[/url] how to get clomid without a prescription

price of amoxicillin without insurance: rexall pharmacy amoxicillin 500mg – generic amoxicillin cost

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin generic

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy cipro cheap

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid buy online

buy paxlovid online [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]paxlovid cost without insurance[/url] paxlovid pharmacy

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro 500mg best prices

amoxicillin 250 mg [url=https://amoxildelivery.pro/#]amoxicillin brand name[/url] amoxicillin 500mg for sale uk

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid covid

ciprofloxacin generic: purchase cipro – buy cipro online canada

amoxicillin capsule 500mg price: how to buy amoxicillin online – amoxicillin medicine over the counter

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can you get clomid without prescription

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# clomid cheap

how to buy doxycycline online [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline 100mg uk[/url] can i buy doxycycline over the counter uk

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin capsule 500mg price

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i buy clomid for sale

where can i order doxycycline [url=https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline hyclate capsules[/url] cost of doxycycline online canada

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline prescription australia

ciprofloxacin 500mg buy online: where can i buy cipro online – ciprofloxacin order online

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid buy online

vibramycin 100mg: tetracycline doxycycline – cost of doxycycline 40 mg

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline over the counter australia

doxycycline 20 [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]best price for doxycycline[/url] doxycycline 100mg cap tab

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin generic

cost of doxycycline online canada [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]buy doxycycline without rx[/url] can i buy doxycycline in india

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# antibiotics cipro

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# cost of generic clomid without insurance

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid price

buy doxycycline 100mg uk [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline over the counter australia[/url] doxycycline 20 mg tablets

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy cipro online

amoxicillin 500 mg tablets: amoxicillin 500mg for sale uk – amoxicillin script

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# buy clomid without rx

buy cipro online [url=https://ciprodelivery.pro/#]ciprofloxacin mail online[/url] purchase cipro

can i buy cheap clomid price: cheap clomid – where to buy clomid pill

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# how to buy amoxicillin online

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg no prescription

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i buy generic clomid without a prescription

doxycycline 40 mg generic coupon [url=https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline capsules 100mg price[/url] doxycycline online with no prescription

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i purchase cheap clomid no prescription

buying generic clomid without a prescription [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]where to buy clomid without dr prescription[/url] how can i get clomid online

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro 500mg best prices

amoxicillin pharmacy price: can i buy amoxicillin online – purchase amoxicillin 500 mg

can you get generic clomid online: buy cheap clomid prices – can you buy cheap clomid

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# where to buy cheap clomid

paxlovid cost without insurance: paxlovid covid – paxlovid india

buy amoxicillin online no prescription: can you buy amoxicillin over the counter in canada – amoxicillin 500 mg purchase without prescription

how to buy doxycycline online: 10 doxycycline gel – doxycycline mono

buy cipro online canada: cipro for sale – buy cipro online usa

http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: buying from online mexican pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican rx online

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medication from mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# mexican mail order pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexico drug stores pharmacies – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/# mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexico pharmacy

medicine in mexico pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico – purple pharmacy mexico price list

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican drugstore online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican rx online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican rx online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]purple pharmacy mexico price list[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican rx online – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican drugstore online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican drugstore online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican mail order pharmacies

http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – reputable mexican pharmacies online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican drugstore online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

medication from mexico pharmacy [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican mail order pharmacies[/url] mexican drugstore online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican mail order pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: medication from mexico pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican rx online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – buying from online mexican pharmacy

reputable mexican pharmacies online: medication from mexico pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – medicine in mexico pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican rx online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] mexican drugstore online

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican rx online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – best online pharmacies in mexico

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican rx online – mexican mail order pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexican rx online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican rx online

mexican drugstore online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: reputable mexican pharmacies online – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

buying from online mexican pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexican rx online

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican pharmaceuticals online – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexican drugstore online

mexican mail order pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican rx online

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican mail order pharmacies[/url] mexican drugstore online

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican rx online

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican rx online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

medication from mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

best online pharmacies in mexico [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – reputable mexican pharmacies online

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexican mail order pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

medicine in mexico pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

medicine in mexico pharmacies: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican rx online

mexican pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican rx online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican rx online

mexican rx online: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican drugstore online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican pharmacy [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]reputable mexican pharmacies online[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexican mail order pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy: reputable mexican pharmacies online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy: purple pharmacy mexico price list – medication from mexico pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] mexican drugstore online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican rx online – buying prescription drugs in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico – best online pharmacies in mexico

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexican pharmacy

purple pharmacy mexico price list: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] medicine in mexico pharmacies

prednisone cost canada [url=https://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]prednisone canada[/url] 30mg prednisone

buy propecia without prescription: cheap propecia price – get cheap propecia no prescription

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# buy nolvadex online

https://prednisonebestprice.pro/# over the counter prednisone pills

tamoxifen mechanism of action [url=https://nolvadexbestprice.pro/#]tamoxifen vs clomid[/url] tamoxifen alternatives

buying generic propecia online: buy propecia for sale – cost propecia

https://prednisonebestprice.pro/# prednisone where can i buy

https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# buy zithromax online

buy cytotec [url=https://cytotecbestprice.pro/#]cytotec abortion pill[/url] Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

buy cytotec over the counter: buy cytotec online fast delivery – Abortion pills online

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec over the counter

prednisone brand name india [url=https://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]prednisone 40mg[/url] buy prednisone canadian pharmacy

prednisone without prescription medication: prednisone tabs 20 mg – can i purchase prednisone without a prescription

http://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec online

https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# zithromax for sale cheap

http://propeciabestprice.pro/# buying cheap propecia without insurance

zithromax 500mg price [url=http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/#]generic zithromax 500mg india[/url] zithromax 250mg

cost of propecia without rx: buying generic propecia price – order cheap propecia without a prescription

tamoxifen hair loss [url=https://nolvadexbestprice.pro/#]buy nolvadex online[/url] tamoxifen moa

http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# purchase zithromax online

zithromax online paypal: zithromax – zithromax generic cost

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec over the counter

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen vs raloxifene

http://prednisonebestprice.pro/# cost of prednisone tablets

generic propecia [url=http://propeciabestprice.pro/#]cheap propecia pills[/url] cost cheap propecia pill

buy cytotec pills online cheap [url=https://cytotecbestprice.pro/#]buy cytotec online[/url] Cytotec 200mcg price

where to get zithromax: generic zithromax india – can you buy zithromax over the counter in mexico

Abortion pills online: purchase cytotec – buy cytotec over the counter

raloxifene vs tamoxifen: tamoxifen dosage – buy tamoxifen

cytotec abortion pill: buy cytotec over the counter – cytotec online

Link pyramid, tier 1, tier 2, tier 3

Primary – 500 hyperlinks with integration embedded in articles on writing domains

Tier 2 – 3000 web address Forwarded connections

Level 3 – 20000 links blend, posts, entries

Using a link network is beneficial for online directories.

Demand:

One link to the platform.

Search Terms.

Accurate when 1 keyword from the page heading.

Observe the additional service!

Essential! Tier 1 connections do not coincide with Tier 2 and Tier 3-order links

A link structure is a instrument for increasing the movement and inbound links of a digital property or social media platform

purchase zithromax online: order zithromax over the counter – zithromax 250 mg australia

https://propeciabestprice.pro/# buy generic propecia prices

https://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen adverse effects

purchase cytotec: cytotec abortion pill – buy cytotec in usa

prednisone 5mg daily: prednisone 10mg for sale – buy prednisone 5mg canada

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online: buy cytotec pills – Abortion pills online

prednisone 5443: cortisol prednisone – prednisone without prescription medication

http://cytotecbestprice.pro/# п»їcytotec pills online

buy generic propecia pill: get propecia without insurance – cost of generic propecia price

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# п»їcytotec pills online

20 mg of prednisone: buy prednisone 20mg – buy prednisone online from canada

zithromax 500: buy azithromycin zithromax – zithromax for sale usa

tamoxifen lawsuit: tamoxifen benefits – tamoxifen

where can i buy zithromax uk: zithromax 250mg – where can i get zithromax over the counter

http://propeciabestprice.pro/# order generic propecia pill

buy cytotec over the counter: purchase cytotec – order cytotec online

http://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen blood clots

https://cialisgenerico.life/# Farmacie online sicure

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: avanafil 100 mg prezzo – farmacie online affidabili

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: avanafil 100 mg prezzo – farmacie online sicure

farmacie online affidabili: avanafil generico – comprare farmaci online all’estero

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: Farmacie che vendono Cialis senza ricetta – comprare farmaci online all’estero

https://kamagrait.pro/# farmacie online affidabili

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: Cialis generico 20 mg 8 compresse prezzo – farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

farmacie online sicure: avanafil senza ricetta – farmacie online sicure

farmacia online: Farmacia online piu conveniente – farmaci senza ricetta elenco

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: Farmacie che vendono Cialis senza ricetta – Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

http://viagragenerico.site/# viagra online in 2 giorni

migliori farmacie online 2024: kamagra gel – farmacie online affidabili

farmacia online senza ricetta: kamagra gel prezzo – farmacia online senza ricetta

farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

top farmacia online: avanafil generico – Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

migliori farmacie online 2024: avanafil in farmacia – Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

https://cialisgenerico.life/# Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

acquisto farmaci con ricetta: kamagra oral jelly – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero: kamagra oral jelly – п»їFarmacia online migliore

top farmacia online: Avanafil compresse – Farmacie online sicure

http://cialisgenerico.life/# comprare farmaci online all’estero

Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: Farmacia online migliore – п»їFarmacia online migliore

viagra cosa serve: viagra farmacia – alternativa al viagra senza ricetta in farmacia

Farmacie online sicure: Avanafil compresse – top farmacia online

miglior sito per comprare viagra online: viagra senza ricetta – viagra originale in 24 ore contrassegno

viagra online spedizione gratuita: viagra prezzo – miglior sito per comprare viagra online

https://avanafil.pro/# migliori farmacie online 2024

farmacia online senza ricetta: Farmacia online migliore – comprare farmaci online all’estero

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: farmaci senza ricetta elenco – farmacia online senza ricetta

https://sildenafil.llc/# viagra samples

cialis online overnight shipping [url=https://tadalafil.auction/#]Buy Tadalafil 20mg[/url] buy cialis no prescription

cialis price comparison no prescription: Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription – cialis and dapoxetine canada

buy viagra order: Buy Viagra online in USA – viagra for women

http://tadalafil.auction/# cialis black 800mg

https://sildenafil.llc/# real viagra without a doctor prescription

http://tadalafil.auction/# whats better viagra or cialis

how to buy cialis in sydney [url=http://tadalafil.auction/#]buy original cialis[/url] buy cialis without prescription

viagra vs cialis: Cheap generic Viagra – buy viagra order

cialis american express: Buy Tadalafil 20mg – cialis australia online shopping

https://sildenafil.llc/# viagra price

viagra without a doctor prescription [url=http://sildenafil.llc/#]buy sildenafil online canada[/url] buy viagra online without a prescription

http://tadalafil.auction/# cialis no perscrtion

generic cialis dapoxetine: cheapest tadalafil – cialis indien bezahlung mit paypal

100 mg viagra lowest price: buy sildenafil online usa – over the counter alternative to viagra

https://sildenafil.llc/# viagra

viagra pills: Viagra without a doctor prescription – generic viagra 100mg

http://tadalafil.auction/# generic cialis florida

generic cialis with dapoxetine 80mg [url=http://tadalafil.auction/#]cheapest tadalafil[/url] cialis viagra levitra young yahoo

buy viagra online without a prescription: Cheap generic Viagra – 100 mg viagra lowest price

cheapest ed pills: ed pills online – cheap erection pills

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

ed prescription online

online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy – buy medicines online in india

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# buy ed meds

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# top 10 pharmacies in india

ed treatment online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# buy ed meds online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# top rated ed pills

best online ed medication

ed pills cheap: ED meds online with insurance – cheapest ed pills

best india pharmacy: Online India pharmacy – pharmacy website india

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# reputable indian online pharmacy

erectile dysfunction online

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# get ed meds today

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

best online ed medication

buy medicines online in india: indian pharmacy – Online medicine order

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# world pharmacy india

best online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy paypal – best online pharmacy india

ed drugs online: Cheap ED pills online – erectile dysfunction medication online

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

ed drugs online: online ed prescription same-day – buy ed medication

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indianpharmacy com

reputable indian online pharmacy: Online pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy

Online medicine home delivery: buy medicines online in india – reputable indian online pharmacy

best india pharmacy: Indian pharmacy international shipping – pharmacy website india

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican rx online

cheapest ed pills: Best ED pills non prescription – pills for erectile dysfunction online

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# cheapest online pharmacy india

Online medicine home delivery: Online India pharmacy – cheapest online pharmacy india

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# ed pills for sale

erectile dysfunction drugs online: cheap ed pills online – cheap boner pills

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: Online India pharmacy – online shopping pharmacy india

best ed pills online: Cheap ED pills online – buy erectile dysfunction pills online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmacy – mexican drugstore online

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# best india pharmacy

best online pharmacy india: Online pharmacy USA – Online medicine home delivery

top 10 online pharmacy in india: Best Indian pharmacy – online pharmacy india

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# ed pills cheap

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Medicines Mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# top rated ed pills

indianpharmacy com: Top online pharmacy in India – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Mexico pharmacy online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# best online pharmacies in mexico

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# india pharmacy mail order

pharmacy website india: Top online pharmacy in India – indian pharmacy online

online prescription for ed: ED meds online with insurance – get ed meds today

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# medication from mexico pharmacy

online pharmacy india: indian pharmacy – top online pharmacy india

indian pharmacy: indian pharmacies safe – Online medicine order

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# erectile dysfunction medications online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: Purple pharmacy online ordering – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

top 10 pharmacies in india: indian pharmacy – reputable indian pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Certified Mexican pharmacy – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable indian pharmacies: Indian pharmacy international shipping – Online medicine home delivery

mexican mail order pharmacies: Best pharmacy in Mexico – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

cheapest online pharmacy india: Online pharmacy USA – top 10 online pharmacy in india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: Certified Mexican pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican mail order pharmacies: Medicines Mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

indian pharmacy online: Online pharmacy – indianpharmacy com

purple pharmacy mexico price list: Certified Mexican pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

Cytotec 200mcg price https://cytotec.pro/# Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

buy lasix online

lipitor brand name cost [url=https://lipitor.guru/#]Atorvastatin 20 mg buy online[/url] lipitor tablets 10mg price

lasix generic name: furosemide online – lasix tablet

how much is lipitor: cheapest ace inhibitor – buy lipitor 20mg

https://furosemide.win/# buy furosemide online

http://tamoxifen.bid/# how does tamoxifen work

buy cytotec pills online cheap https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen dose

furosemide

zestril 40 mg tablet: Buy Lisinopril 20 mg online – buy cheap lisinopril 40 mg no prescription

low dose tamoxifen [url=https://tamoxifen.bid/#]tamoxifen headache[/url] tamoxifen lawsuit

buy cytotec online http://lipitor.guru/# lipitor

lasix 40 mg

lasix: lasix generic name – furosemide 40 mg

tamoxifen estrogen [url=http://tamoxifen.bid/#]buy tamoxifen online[/url] tamoxifen bone pain

https://furosemide.win/# lasix 40 mg

lasix medication: cheap lasix – lasix furosemide

https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen and osteoporosis

buy cytotec https://furosemide.win/# lasix 100 mg

furosemide 40mg

lasix 100 mg [url=https://furosemide.win/#]furosemide online[/url] lasix dosage

buy cytotec over the counter https://furosemide.win/# lasix 100mg

lasix 40 mg

http://lipitor.guru/# lipitor 40 mg price india

buy cytotec online https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 10 mg no prescription

lasix 100 mg

https://lisinopril.guru/# cheapest price for lisinopril

nolvadex pct [url=https://tamoxifen.bid/#]buy tamoxifen online[/url] buy nolvadex online

where can i buy nolvadex: Purchase Nolvadex Online – tamoxifen buy

lisinopril 20 mg discount: cheap lisinopril – lisinopril in mexico

buy cytotec over the counter http://lipitor.guru/# lipitor canada pharmacy

lasix

https://lipitor.guru/# cheap lipitor generic

cytotec abortion pill https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec in usa

lasix 20 mg

https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 5 mg canada

buy cytotec in usa: buy cytotec online – buy cytotec

lipitor prices compare: cheapest ace inhibitor – price canada lipitor 20mg

purchase cytotec http://furosemide.win/# lasix uses

lasix 40mg

lisinopril generic price comparison: Lisinopril online prescription – lisinopril brand name australia

https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 40 mg on line

buy cytotec pills https://furosemide.win/# lasix 40mg

furosemide 40mg

https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 5mg pill

мастер айфон москва

tamoxifen chemo: Purchase Nolvadex Online – tamoxifen bone density

lisinopril 10 mg best price: drug lisinopril 5 mg – lisinopril drug

п»їcytotec pills online https://tamoxifen.bid/# nolvadex for pct

furosemida

Cytotec 200mcg price: buy misoprostol tablet – п»їcytotec pills online

https://cytotec.pro/# Abortion pills online

buy cytotec over the counter https://lipitor.guru/# buy cheap lipitor online

lasix uses

can i buy lisinopril online: buy lisinopril – lisinopril 12.5 mg 10 mg

https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec over the counter

buy lisinopril: zestril online – lisinopril 5mg tabs

nolvadex during cycle: buy tamoxifen citrate – tamoxifen side effects forum

Abortion pills online https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec pills online cheap

lasix 20 mg

tamoxifen vs raloxifene: Purchase Nolvadex Online – tamoxifen men

buy cytotec over the counter https://lipitor.guru/# lipitor 20mg canada price

lasix

furosemida: cheap lasix – furosemida 40 mg

tamoxifen endometrium: tamoxifen warning – tamoxifen postmenopausal

tamoxifen cyp2d6: buy tamoxifen online – tamoxifen headache

buy cytotec over the counter http://lisinopril.guru/# zestril 2.5 mg tablets

lasix side effects

effexor and tamoxifen: buy tamoxifen online – generic tamoxifen

buy cytotec over the counter https://furosemide.win/# buy furosemide online

lasix pills

lisinopril 10 mg no prescription: cheap lisinopril – 10 mg lisinopril cost

сервисный ремонт apple

lisinopril generic 20 mg: Lisinopril refill online – zestril 5 mg prices

п»їcytotec pills online http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril pill 20mg

buy furosemide online

furosemide 40mg: furosemide online – lasix tablet

buy cytotec pills online cheap https://lisinopril.guru/# generic for prinivil

lasix 100 mg tablet

buy cytotec pills online cheap: cytotec best price – п»їcytotec pills online

создать сайт по ремонту телефонов

canadian pharmacy meds: canadian pharmacy world – my canadian pharmacy reviews

https://mexstarpharma.com/# medication from mexico pharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india [url=https://easyrxindia.shop/#]india pharmacy mail order[/url] indianpharmacy com

http://mexstarpharma.com/# best online pharmacies in mexico

https://easyrxindia.shop/# india online pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://mexstarpharma.online/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian drug pharmacy

http://easyrxcanada.com/# canadianpharmacymeds com

indian pharmacies safe [url=https://easyrxindia.shop/#]top 10 online pharmacy in india[/url] п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

canadian online drugs: my canadian pharmacy – best online canadian pharmacy

https://mexstarpharma.online/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

top online pharmacy india: buy prescription drugs from india – world pharmacy india

mail order pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – india online pharmacy

drugs from canada [url=http://easyrxcanada.com/#]best online canadian pharmacy[/url] canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us

http://easyrxindia.com/# mail order pharmacy india

indian pharmacy online: india pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy

http://mexstarpharma.com/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=https://mexstarpharma.online/#]medication from mexico pharmacy[/url] п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

http://easyrxcanada.com/# online pharmacy canada

https://easyrxcanada.online/# canada pharmacy reviews

pharmacy website india: india pharmacy – pharmacy website india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican drugstore online

indian pharmacy: reputable indian online pharmacy – indian pharmacies safe

https://easyrxcanada.online/# canadian pharmacy 24h com safe

https://easyrxcanada.online/# canadian pharmacy phone number

canadian pharmacy: canadian mail order pharmacy – canadian pharmacy price checker

canada drugs online: canada drug pharmacy – canadian valley pharmacy

http://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian world pharmacy

https://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian pharmacies compare

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican pharmaceuticals online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

ремонт телевизора москва

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: где ремонтируют телефоны

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт телефонов москва рядом

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

india pharmacy: top online pharmacy india – world pharmacy india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://easyrxindia.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

http://mexstarpharma.com/# best online pharmacies in mexico

canada pharmacy 24h: canadian pharmacy ratings – legit canadian pharmacy

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

2024 en iyi slot siteleri: en iyi slot siteleri 2024 – slot siteleri

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: мастер по ремонту телефонов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

canl? slot siteleri: deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri – en cok kazandiran slot siteleri

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков, макбуков и другой компьютерной техники.

Мы предлагаем:мак сервис москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

casino slot siteleri: slot siteleri guvenilir – bonus veren casino slot siteleri

http://slotsiteleri.bid/# guvenilir slot siteleri 2024

deneme bonusu veren siteler: slot oyunlar? siteleri – deneme bonusu veren siteler

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту квадрокоптеров и радиоуправляемых дронов.

Мы предлагаем:надежный сервис ремонта квадрокоптеров

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://sweetbonanza.network/# sweet bonanza yasal site

bonus veren siteler: deneme bonusu – bonus veren siteler

slot bahis siteleri: slot siteleri bonus veren – deneme bonusu veren siteler

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков, imac и другой компьютерной техники.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт аймаков на дому

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

priligy generico It is sometimes difficult to tell the differences on imaging between primary cancer of the renal pelvis and a metastatic lesion

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт пк в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

ремонт айфонов москва

en guvenilir slot siteleri: en yeni slot siteleri – yeni slot siteleri

http://sweetbonanza.network/# sweet bonanza demo

guvenilir slot siteleri: slot casino siteleri – en yeni slot siteleri

oyun siteleri slot: deneme bonusu veren siteler – deneme bonusu veren siteler

slot siteleri bonus veren: en iyi slot siteler – deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# bonus veren siteler

deneme veren slot siteleri: en iyi slot siteleri – deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri

slot bahis siteleri: deneme bonusu veren siteler – yeni slot siteleri

http://slotsiteleri.bid/# oyun siteleri slot

slot oyun siteleri: slot oyunlar? siteleri – slot siteleri bonus veren

ремонт эппл вотч

http://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

guvenilir slot siteleri: en yeni slot siteleri – slot siteleri guvenilir

ремонт iwatch

https://sweetbonanza.network/# sweet bonanza yasal site

bonus veren slot siteleri: en cok kazandiran slot siteleri – guvenilir slot siteleri

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планетов в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: вызвать мастера по ремонту айпадов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

guvenilir slot siteleri: en guvenilir slot siteleri – slot oyun siteleri

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт ноутбуков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:сервисные центры в санкт петербурге

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту радиоуправляемых устройства – квадрокоптеры, дроны, беспилостники в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: квадрокоптеры сервис

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

вавада рабочее зеркало [url=https://vavada.auction/#]vavada casino[/url] вавада рабочее зеркало

пин ап: pin up казино – пин ап казино

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планетов в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт планшетов apple в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

1win вход: 1вин зеркало – 1вин

пин ап: пинап казино – пин ап казино вход

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервис центр в петербурге

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту радиоуправляемых устройства – квадрокоптеры, дроны, беспилостники в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: квадрокоптеры сервис

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники

пин ап: пин ап зеркало – пинап казино

http://1xbet.contact/# 1xbet скачать

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт ноутбуков москва центр

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт крупногабаритной техники в петрбурге

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи екб

pin up: pin up casino – пинап казино

пин ап казино вход [url=http://pin-up.diy/#]пин ап[/url] пин ап вход

https://1xbet.contact/# 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня

vavada: вавада рабочее зеркало – вавада зеркало

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники

pin up: пин ап зеркало – пинап казино

пин ап: пин ап казино – пин ап

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт цифровой техники москва

казино вавада: казино вавада – вавада

pin up: пин ап казино – пин ап вход

пин ап: пин ап казино вход – pin up

пин ап зеркало: пин ап зеркало – pin up

https://pin-up.diy/# pin up казино

pin up casino: пин ап – пин ап зеркало

1xbet зеркало: 1хбет зеркало – 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня

http://pin-up.diy/# pin up casino

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – тех профи

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту Apple iPhone в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт айфонов на дому в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

ближайший ремонт телефонов

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту источников бесперебойного питания.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт бесперебойников

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://vavada.auction/# vavada casino

vavada casino: вавада – вавада рабочее зеркало

1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия: 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия – 1хбет официальный сайт

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в новосибирске

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту Apple iPhone в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт телефонов айфон в москве адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту источников бесперебойного питания.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт ибп москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

buy priligy in the usa Second, the recommendation stating that baseline gynecologic examination before initiation of treatment and annually thereafter was necessary for women taking tamoxifen was removed

1вин зеркало: 1вин зеркало – 1вин официальный сайт

http://1xbet.contact/# зеркало 1хбет

1хбет зеркало: зеркало 1хбет – 1xbet

http://pin-up.diy/# пин ап зеркало

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервисный центр в барнаул

сервисный ремонт телевизоров

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервис центр в челябинске

вавада: vavada – vavada casino

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи услуги

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в челябинске

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту варочных панелей и индукционных плит.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт варочных панелей в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт бытовой техники в екб

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://onlineph24.com/# clozapine pharmacy directory

bupropion xl pharmacy

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:сервис центры бытовой техники екатеринбург

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту варочных панелей и индукционных плит.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт электрических варочных панелей на дому москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://pharm24on.com/# viagra vipps pharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india

fluconazole mexico pharmacy: viagra online pharmacy india – cialis pharmacy india

https://easydrugrx.com/# ca board of pharmacy

Starlix

pom pharmacy viagra: clindamycin target pharmacy – tricare pharmacy

цифровой фотоаппарат ремонт

https://onlineph24.com/# top rx pharmacy

prilosec online pharmacy

ремонт фотоаппарата

https://onlineph24.com/# online pharmacy cytotec no prescription

viagra in dubai pharmacy [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]Mobic[/url] provigil pharmacy

publix pharmacy wellbutrin: legitimate online pharmacy viagra – qatar pharmacy cialis

https://drstore24.com/# buspirone pharmacy

propecia target pharmacy

https://pharm24on.com/# medco pharmacy viagra

xl pharmacy cialis

https://drstore24.com/# mexican pharmacy online reviews

online pharmacy ed [url=https://drstore24.com/#]viagra cost at pharmacy[/url] best online pharmacy clomid

total rx pharmacy: lamotrigine target pharmacy – target pharmacy zoloft price

https://pharm24on.com/# online pharmacy uk

Doxycycline [url=https://drstore24.com/#]generic levitra online pharmacy[/url] tamiflu pharmacy

https://onlineph24.com/# your rx pharmacy grapevine tx

sumatriptan pharmacy uk [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]singapore pharmacy online store[/url] world pharmacy store discount number

https://onlineph24.com/# baclofen river pharmacy

best pharmacy to buy cialis

phuket pharmacy viagra: cialis united pharmacy – online pharmacy adipex

online pharmacy ambien no prescription: price of percocet at pharmacy – discount pharmacy tadalafil

https://onlineph24.com/# doxycycline uk pharmacy

rx crossroads pharmacy refill

italian pharmacy viagra: super pharmacy – world pharmacy viagra

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи услуги

legit mexican pharmacy: viagra target pharmacy – online pharmacy fioricet

https://drstore24.com/# online pharmacy depo provera

rx pharmacy online [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]pharmacy degree online[/url] best online pharmacy tadalafil

Все свежие акции и бонусы доступны на https://888starz.today, не упустите свой шанс.

https://onlineph24.com/# legitimate online pharmacy no prescription

new zealand pharmacy motilium [url=https://drstore24.com/#]fry’s food store pharmacy hours[/url] clindamycin people’s pharmacy

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – выездной ремонт бытовой техники в челябинске

tamiflu pharmacy coupons: generic lexapro online pharmacy – amoxicillin mexican pharmacy

pharmacy degree online: can i buy viagra from a pharmacy – trusted overseas pharmacies

https://drstore24.com/# pharmacy home delivery

meijer pharmacy store hours [url=https://onlineph24.com/#]Viagra Super Active[/url] best online pharmacy no prescription viagra

cabergoline pharmacy: ramesh rx pharmacy – best retail pharmacy viagra price

https://pharm24on.com/# meijer pharmacy free lipitor

walgreen pharmacy online [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]legal online pharmacy coupon code[/url] elevit online pharmacy

buy cialis online pharmacy: augmentin pharmacy prices – medical pharmacy west

pharmacy direct gabapentin: online pharmacy denmark – euro pharmacy viagra

chloramphenicol pharmacy: online pharmacy legit – ambien internet pharmacy

https://drstore24.com/# proscar pharmacy online

spironolactone inhouse pharmacy [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]Trecator SC[/url] cialis online pharmacy usa

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту фото техники от зеркальных до цифровых фотоаппаратов.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт фотокамер

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

https://pharm24on.com/# tretinoin online pharmacy

lisinopril online pharmacy no prescription [url=https://drstore24.com/#]cetirizine pharmacy[/url] hydrochlorothiazide online pharmacy

safeway pharmacy methotrexate error: zoloft indian pharmacy – buy viagra from us pharmacy

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту фото техники от зеркальных до цифровых фотоаппаратов.

Мы предлагаем: диагностика и ремонт фотоаппаратов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

safeway pharmacy: precision pharmacy omeprazole – provigil pharmacy

Comments are closed.