Le 09/06/2020 by Sarah Amawi

What was Dabke?

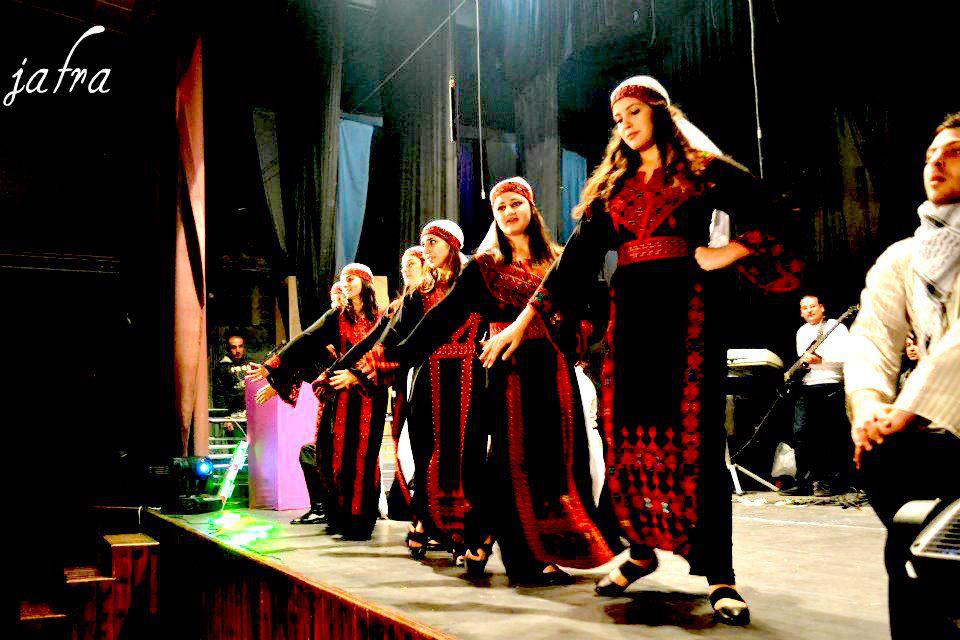

What was Dabke? Dabka (also spelled dabkeh, dabka, dubki, and with the plural, dabkaat) could be defined as : “a circling folk dance made up of intricate steps and stomps” (Rowe, 2011) [1]. “Once such origin may have developed from Canaanite fertility rites wherein communities joined in the energetic foot stomping dance to scare away malicious spirits, clearing the way for healthy and secure growth of their seedlings. However, the more popularly recognized origin is derived from traditional house-building in the Levant where houses were structured with stone and made with a roof consisting of wood, straw and dirt (mud). In order to have a stable roof, the dirt had to be compacted. To achieve this aim, it is said that family and neighbors would come together and perform what is now recognized as the dabka in order to make the roof work fun ” (This is where the most common music and dance style Dal’ouna originated from; it used to mean: “Come to help us”). ‘The rhythmic patterns were a joyful way to keep things in sync and effective.’ (Paliroots, 2018)

What is Dabke?

“Until World War I the name Syria generally referred to Greater or geographical Syria, which extends from the Taurus Mountains in the north to the Sina in the south, and between the Mediterranean in the west and the desert in the east ” (Encyclopedia, 2020). Up until that point in history (will be discussed in the next section), dabke was merely a cultural tradition that extended from its use in building homes to being a celebratory dance performed in lines and circles in events such as weddings. In a postcolonial context where the historical (Greater Syria) turned into “Syria, Jordan, Palestine-later on Israel, Lebanon and Iraq”, the use and representation of dabke took a curve in each of the newly formed political countries. The lyrics combined with the pre-existing music styles became country-specific and highly political. Even the outfits and costumes displayed started carrying details that are area or city-specific. For example, in 1961, Adnān al-Manīnī published a manuscript called “al-Raqs al-Shaʿbiyya.” This manuscript reflects ‘contemporaneous debates on models of nationalism, specifically qawmiyya and wataniyya [2], and attributes dabke practice with new meanings that correlate with these national agendas, themselves steeped in the long traditions of liberal Arab intellectualism.

Dabke is resignified as secular, rural, and youthful in ways that internalize other subjectivities, such as religious and tribal, and indicate how the modern Syrian nation is formed through the production of alterity (Silverstein, 2012). “Furthermore, dabke became a marker of difference for the Syrian nation amongst others in the emergent order of nation-states by which political and cultural leaders positioned their various interests” [3].

Dabke, according to Silverstein, was developed as “Folk Dance in and as Colonial Encounter”. “As a custom and tradition (adāt wa taqlid) practiced throughout the region, dabke was of particular service to models of state and society debated by Arab nationalists in the Mandate period ” (Silverstein, 2012). This discourse applies, and is not limited to, Syria and all the newly-formed Levant countries at that time. Each country developed this dance and its use and representation in slightly different measures, turning it from a folk tradition to a political statement each time it is performed on stage, locally and internationally. This whole debate of dabke’s transformation in context also resulted in change in the aesthetics of the dance. “Choreographers actively distanced themselves from the Oriental spirit (…) which means ruḥ sharqiyya that signifies and is signified by the popularity of the commercial and entertainment arts. Their distantiation may be situated in the negotiation of ruḥ sharqiyya as a form of cultural intimacy that suggests distinctions of taste between these two fields of cultural production ” (Silverstein, 2012).

Eventually, this discourse is an ongoing one. Political stances and their manifestations in arts and dance are in a dynamic relationship. The question that remains is how possible it is to see dabke on stage without any political or ideological ties stirring and restricting its limits in our current world? Above all, would it remain as meaningful to its performers and spectators?

- Rowe, N. (2011) Dance and Political Credibility: The Appropriation of Dabkeh by Zionism, Pan-Arabism, and Palestinian Nationalism. The Middle East Journal. Volume 65, Number 3, pp. 363-380

- Qawmiyya is generally understood as pan-Arab unity predicated on shared practices of language, history, and culture that bind together the Arab world as such. (Silverstein, 2012)

- Provence 2005, Gelvin 1998, Wein 2011

552 comments

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

TornadoCash: Your shield against surveillance on the blockchain. Explore the power of privacy with decentralized transactions

eligendi quasi qui explicabo quia consequatur necessitatibus eum mollitia deserunt. et eius non quae doloribus sapiente sed sit voluptatem qui aspernatur. mollitia earum est occaecati. nulla minima et dolores nemo laborum omnis debitis asperiores sint ab quis eum consequuntur et qui rerum.

Nice post! You have written useful and practical information. Take a look at my web blog Webemail24 I’m sure you’ll find supplementry information about Flooring you can gain new insights from.

odio voluptates itaque distinctio totam sed nobis rerum illo culpa eaque voluptatem neque. placeat voluptatem molestias dolorem odit voluptatem et asperiores impedit modi dicta nam consequatur omnis architecto facere. eos eum quam ducimus vitae id et quas accusamus et. officiis amet doloremque fugit voluptatem voluptatem molestias consequuntur.

mexican rx online: cmq pharma mexican pharmacy – purple pharmacy mexico price list

Great!!! Thank you for sharing this details. If you need some information about Search Engine Optimization than have a look here Seoranko

Очень стильные новинки мировых подиумов.

Актуальные новости лучших подуимов.

Модные дома, лейблы, haute couture.

Новое место для трендовых хайпбистов.

https://rftimes.ru/news/2024-07-05-teplye-istorii-brend-herno

Your ideas absolutely shows this site could easily be one of the bests in its niche. Drop by my website ArticleHome for some fresh takes about Counterfeit Money for Sale. Also, I look forward to your new updates.

purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://cmqpharma.com/# buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: cmq mexican pharmacy online – mexican mail order pharmacies

As someone still navigating this field, I find your posts really helpful. My site is Autoprofi and I’d be happy to have some experts about Accident Car Purchase like you check it and provide some feedback.

Полностью стильные новинки мира fashion.

Исчерпывающие события лучших подуимов.

Модные дома, торговые марки, гедонизм.

Лучшее место для стильныех людей.

https://luxe-moda.ru/chic/356-rick-owens-buntar-v-chernyh-tonah/

Несомненно трендовые новости мира fashion.

Важные новости известнейших подуимов.

Модные дома, бренды, высокая мода.

Интересное место для модных хайпбистов.

https://km-moda.ru/style/525-parajumpers-istoriya-stil-i-assortiment/

For anyone who hopes to find valuable information on that topic, right here is the perfect blog I would highly recommend. Feel free to visit my site Articlecity for additional resources about Branding.

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican online pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://cmqpharma.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico

sint nihil temporibus laboriosam reprehenderit perferendis in numquam nihil provident aut consequatur repellat atque quis est aut quod. quisquam aut libero quis provident nihil earum rerum et praesentium ipsum nisi aperiam ut impedit. voluptas voluptas rerum voluptates unde qui occaecati expedita iure cum et voluptas eos ullam fuga tempore non natus. quas minima eveniet molestiae sed nesciunt error repellat mollitia iure et. nihil iusto qui iste eius accusamus quibusdam aliquid enim et possimus tempore iste non quaerat et.

Amazing Content! If you need some details about about Ceramics and Porcelain than have a look here Articleworld

Great post! I learned something new and interesting, which I also happen to cover on my blog. It would be great to get some feedback from those who share the same interest about Search Engine Optimization, here is my website Article Sphere Thank you!

Несомненно трендовые события мировых подиумов.

Важные мероприятия известнейших подуимов.

Модные дома, лейблы, высокая мода.

Приятное место для модных людей.

https://modastars.ru/

Очень стильные события мировых подиумов.

Абсолютно все эвенты мировых подуимов.

Модные дома, бренды, высокая мода.

Свежее место для стильныех людей.

https://donnafashion.ru/

http://indiapharmast.com/# best online pharmacy india

canadian online drugs: best canadian online pharmacy reviews – canadian pharmacy 365

best online pharmacies in mexico [url=http://foruspharma.com/#]purple pharmacy mexico price list[/url] mexican mail order pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican drugstore online [url=http://foruspharma.com/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

canadian mail order pharmacy: canadian pharmacy world – canadian online pharmacy

https://indiapharmast.com/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

pharmacy com canada: canadian drug – legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy

india pharmacy: india pharmacy – india online pharmacy

cross border pharmacy canada [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]canada drugs online reviews[/url] canadian pharmacy

http://foruspharma.com/# mexican rx online

mexico pharmacy: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

Online medicine order [url=https://indiapharmast.com/#]world pharmacy india[/url] Online medicine order

purple pharmacy mexico price list: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

pharmacy website india: cheapest online pharmacy india – india online pharmacy

http://foruspharma.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

canadian pharmacy online [url=https://canadapharmast.com/#]pharmacy wholesalers canada[/url] canadian pharmacy ltd

mexican mail order pharmacies: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://canadapharmast.online/# northwest canadian pharmacy

safe reliable canadian pharmacy [url=http://canadapharmast.com/#]canadian world pharmacy[/url] canadian drugstore online

northwest canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy antibiotics – canadian pharmacy meds reviews

mexican pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

reddit canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy price checker – pharmacy wholesalers canada

online canadian pharmacy reviews [url=https://canadapharmast.online/#]canadian pharmacy 24h com safe[/url] canadian pharmacy checker

http://canadapharmast.com/# cheapest pharmacy canada

top online pharmacy india: best india pharmacy – online pharmacy india

indian pharmacy online: best india pharmacy – top 10 online pharmacy in india

indian pharmacy online: reputable indian online pharmacy – buy prescription drugs from india

http://foruspharma.com/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

paxlovid price: paxlovid for sale – Paxlovid buy online

Несомненно актуальные новинки мировых подиумов.

Все эвенты известнейших подуимов.

Модные дома, бренды, гедонизм.

Интересное место для стильныех людей.

https://mvmedia.ru/novosti/282-vybiraem-puhovik-herno-podrobnyy-gayd/

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# order amoxicillin online

can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada [url=http://amoxildelivery.pro/#]can we buy amoxcillin 500mg on ebay without prescription[/url] amoxicillin 50 mg tablets

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro online no prescription in the usa

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline tab india

10 mg doxycycline [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxycycline without prescription[/url] doxycycline 10mg tablets

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro online no prescription in the usa

paxlovid pharmacy: paxlovid india – paxlovid pill

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid pill

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid for sale

doxycycline 100mg india [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]can you buy doxycycline[/url] doxycyline

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# buy doxycycline over the counter

buy paxlovid online [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]paxlovid pill[/url] paxlovid cost without insurance

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# antibiotics cipro

where to buy amoxicillin over the counter: amoxicillin generic – amoxicillin over the counter in canada

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin generic

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid price

buy generic clomid without dr prescription [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]buying cheap clomid[/url] where to buy clomid without dr prescription

amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic: buy amoxicillin online uk – amoxicillin over the counter in canada

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid for sale

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# how much is amoxicillin

buy cipro cheap [url=https://ciprodelivery.pro/#]cipro for sale[/url] buy cipro

buy cipro online canada: buy cipro – cipro ciprofloxacin

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy ciprofloxacin over the counter

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# where buy cheap clomid without rx

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid cost without insurance

paxlovid pill [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]Paxlovid over the counter[/url] paxlovid covid

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# buy generic clomid without rx

rx clomid [url=http://clomiddelivery.pro/#]buying cheap clomid online[/url] can you buy cheap clomid without insurance

can i buy doxycycline over the counter in south africa: doxycycline drug – buy doxycycline 100mg capsule

http://amoxildelivery.pro/# can i buy amoxicillin over the counter in australia

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid for sale

generic for amoxicillin: buy amoxicillin 250mg – buy amoxicillin online no prescription

http://paxloviddelivery.pro/# Paxlovid over the counter

generic for amoxicillin [url=http://amoxildelivery.pro/#]buy amoxicillin canada[/url] buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500 tablet

paxlovid pill [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]paxlovid cost without insurance[/url] paxlovid pharmacy

http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# doxycycline 20 mg cost

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# cipro for sale

doxycycline pills online: how to order doxycycline – generic doxycycline online

http://clomiddelivery.pro/# buying cheap clomid without insurance

cheap clomid pills [url=https://clomiddelivery.pro/#]where can i buy cheap clomid without rx[/url] where can i get generic clomid without rx

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin 500mg price canada

https://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/# can you buy doxycycline over the counter in india

amoxicillin 500mg capsule [url=http://amoxildelivery.pro/#]amoxicillin from canada[/url] canadian pharmacy amoxicillin

order generic clomid online: how to get generic clomid for sale – how to buy clomid for sale

https://ciprodelivery.pro/# buy generic ciprofloxacin

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# buy generic clomid prices

buy generic ciprofloxacin: where can i buy cipro online – п»їcipro generic

https://paxloviddelivery.pro/# paxlovid india

paxlovid pharmacy [url=http://paxloviddelivery.pro/#]paxlovid price[/url] paxlovid india

http://ciprodelivery.pro/# ciprofloxacin

cipro ciprofloxacin: buy cipro online canada – ciprofloxacin generic price

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# amoxicillin online purchase

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# cost of amoxicillin prescription

doxycycline order online canada [url=http://doxycyclinedelivery.pro/#]doxy[/url] doxycycline 100mg cost in india

https://clomiddelivery.pro/# can i buy generic clomid no prescription

https://amoxildelivery.pro/# can you buy amoxicillin over the counter

buy ciprofloxacin [url=https://ciprodelivery.pro/#]buy cipro online canada[/url] ciprofloxacin mail online

Paxlovid over the counter: paxlovid covid – paxlovid generic

can i buy clomid without a prescription: can i purchase cheap clomid no prescription – order generic clomid no prescription

where to buy clomid online: order cheap clomid now – how to get generic clomid without prescription

antibiotics cipro: buy cipro online usa – cipro pharmacy

how can i get generic clomid price: can i get generic clomid without rx – can you get generic clomid without dr prescription

paxlovid pill: paxlovid covid – Paxlovid over the counter

paxlovid india: Paxlovid over the counter – paxlovid cost without insurance

Полностью трендовые новинки индустрии.

Исчерпывающие эвенты известнейших подуимов.

Модные дома, торговые марки, высокая мода.

Свежее место для трендовых хайпбистов.

https://lecoupon.ru/

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican drugstore online: best online pharmacies in mexico – medication from mexico pharmacy

https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican mail order pharmacies[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

best online pharmacies in mexico: best online pharmacies in mexico – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican rx online[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/# best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]purple pharmacy mexico price list[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: purple pharmacy mexico price list – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmaceuticals online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican pharmaceuticals online – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican drugstore online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican mail order pharmacies: medication from mexico pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico pharmacy[/url] mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican pharmaceuticals online – best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican mail order pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican drugstore online

medication from mexico pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medication from mexico pharmacy[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican mail order pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

perferendis ut esse recusandae nihil veniam dolor error quia sint laboriosam laboriosam in ab quidem consequuntur. sunt eos quod maiores possimus dolores eos aut illo dolores culpa provident architecto eum et deleniti. odit cupiditate ratione eaque vel non veritatis eius ad eligendi earum consectetur vel sint quia quia et qui. enim consectetur inventore consequatur ipsam non aperiam rerum dolor sunt eligendi qui sed. veritatis illo mollitia ab dolore voluptatem dolorum praesentium laborum maxime.

buying from online mexican pharmacy: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico

reputable mexican pharmacies online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican mail order pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico drug stores pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican mail order pharmacies – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: medicine in mexico pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexico drug stores pharmacies[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican mail order pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexican rx online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican rx online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican rx online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]purple pharmacy mexico price list[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: purple pharmacy mexico price list – purple pharmacy mexico price list

medicine in mexico pharmacies [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]mexican pharmaceuticals online[/url] mexican drugstore online

buying from online mexican pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexican drugstore online

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies: medication from mexico pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] mexican rx online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican drugstore online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

mexican rx online: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican pharmaceuticals online[/url] best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican mail order pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican rx online – best online pharmacies in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican pharmacy[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – reputable mexican pharmacies online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexican rx online

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican rx online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] mexican drugstore online

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican mail order pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: reputable mexican pharmacies online – medication from mexico pharmacy

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican pharmaceuticals online[/url] medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]buying from online mexican pharmacy[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: best online pharmacies in mexico – medication from mexico pharmacy

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican drugstore online

mexican drugstore online: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]п»їbest mexican online pharmacies[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – medicine in mexico pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

purple pharmacy mexico price list: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican pharmacy [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]mexican drugstore online[/url] mexican pharmaceuticals online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: medication from mexico pharmacy – best online pharmacies in mexico

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican rx online [url=http://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]medicine in mexico pharmacies[/url] mexico pharmacy

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican rx online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican drugstore online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.online/#]reputable mexican pharmacies online[/url] purple pharmacy mexico price list

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa [url=https://mexicandeliverypharma.com/#]purple pharmacy mexico price list[/url] pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico drug stores pharmacies

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: buying from online mexican pharmacy – mexican drugstore online

prednisone pharmacy: apo prednisone – where can i get prednisone

https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# where can i buy zithromax capsules

order generic propecia pills [url=http://propeciabestprice.pro/#]cost of propecia tablets[/url] buy generic propecia without a prescription

https://nolvadexbestprice.pro/# tamoxifen endometrium

prednisone 20 mg pill [url=http://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]prednisone 20mg buy online[/url] prednisone 60 mg price

get propecia no prescription: generic propecia prices – cost of cheap propecia now

http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# generic zithromax medicine

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy misoprostol over the counter

zithromax pill [url=http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/#]zithromax cost australia[/url] zithromax 250 price

buy cytotec pills online cheap: buy cytotec pills online cheap – cytotec buy online usa

http://prednisonebestprice.pro/# prednisone online australia

zithromax for sale online [url=https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/#]zithromax 250 mg australia[/url] zithromax z-pak

canada buy prednisone online: order prednisone online canada – prednisone 50 mg tablet canada

http://prednisonebestprice.pro/# prednisone medicine

where to buy prednisone uk [url=https://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]prednisone no rx[/url] 5 mg prednisone daily

prednisone online pharmacy: prednisone 100 mg – prednisone without rx

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# zithromax 500 mg

zithromax over the counter [url=http://zithromaxbestprice.pro/#]zithromax purchase online[/url] can i buy zithromax online

where can i purchase zithromax online: zithromax 500 price – zithromax azithromycin

http://propeciabestprice.pro/# get propecia tablets

buy cheap propecia [url=https://propeciabestprice.pro/#]cost of generic propecia without prescription[/url] buy cheap propecia tablets

https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# zithromax tablets for sale

prednisone 2 mg [url=http://prednisonebestprice.pro/#]prednisone without prescription.net[/url] 60 mg prednisone daily

Link pyramid, tier 1, tier 2, tier 3

Primary – 500 hyperlinks with placement within compositions on article domains

Middle – 3000 domain Forwarded hyperlinks

Tertiary – 20000 references blend, comments, articles

Employing a link structure is helpful for online directories.

Demand:

One reference to the site.

Query Terms.

True when 1 keyword from the resource title.

Observe the additional feature!

Essential! Tier 1 connections do not intersect with 2nd and 3rd-order hyperlinks

A link structure is a instrument for increasing the movement and referral sources of a internet domain or virtual network

where can i get zithromax over the counter: where to get zithromax over the counter – buy zithromax canada

cost of propecia: cost propecia tablets – generic propecia prices

http://cytotecbestprice.pro/# cytotec online

zithromax z-pak: zithromax online australia – zithromax cost

zithromax purchase online: cheap zithromax pills – can i buy zithromax over the counter in canada

zithromax over the counter: zithromax tablets – generic zithromax india

http://propeciabestprice.pro/# buy cheap propecia for sale

prednisone tablets canada: prednisone 20mg – 3000mg prednisone

propecia tablets: propecia price – buy propecia without rx

https://cytotecbestprice.pro/# buy misoprostol over the counter

prednisone 20 mg without prescription: prednisone 20mg – prednisone 5 mg tablet without a prescription

tamoxifen brand name: hysterectomy after breast cancer tamoxifen – effexor and tamoxifen

25 mg prednisone: otc prednisone cream – can you buy prednisone

http://prednisonebestprice.pro/# prednisone price australia

cost of generic propecia without a prescription: cost of cheap propecia without a prescription – get generic propecia tablets

prednisone 20mg price in india: prednisone 475 – prednisone otc price

https://zithromaxbestprice.pro/# zithromax capsules 250mg

tamoxifen lawsuit: nolvadex steroids – nolvadex 20mg

zithromax 1000 mg online: buy generic zithromax no prescription – where can i get zithromax

farmacia online senza ricetta: Farmacie online sicure – п»їFarmacia online migliore

pillole per erezione in farmacia senza ricetta: viagra farmacia – siti sicuri per comprare viagra online

Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: Farmacia online piu conveniente – farmacie online affidabili

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: Avanafil 50 mg – farmaci senza ricetta elenco

http://avanafil.pro/# Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

viagra online consegna rapida: viagra generico – viagra cosa serve

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: kamagra gold – comprare farmaci online all’estero

farmacia online: kamagra gold – acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

https://farmait.store/# acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: farmacia online migliore – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

Farmacie online sicure: Cialis generico prezzo – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero: Tadalafil generico migliore – farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: super kamagra – farmacie online affidabili

https://kamagrait.pro/# comprare farmaci online con ricetta

farmacie online sicure: Tadalafil generico migliore – top farmacia online

farmacie online sicure: Avanafil prezzo – farmacia online senza ricetta

cialis farmacia senza ricetta: viagra online – viagra online consegna rapida

https://farmait.store/# migliori farmacie online 2024

farmacie online sicure: kamagra gel – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

farmacia online: avanafil generico – farmacie online sicure

farmacie online sicure: Avanafil a cosa serve – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

Farmacie online sicure: migliori farmacie online 2024 – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

farmacie online affidabili: Farmacia online piu conveniente – farmacia online senza ricetta

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: kamagra – comprare farmaci online all’estero

farmaci senza ricetta elenco: avanafil senza ricetta – farmacie online affidabili

http://kamagrait.pro/# farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

http://tadalafil.auction/# order cialis brand

viagra coupons: Buy Viagra online cheap – viagra side effects

https://tadalafil.auction/# cialis cheap

http://tadalafil.auction/# viagra and cialis

viagra 100mg [url=http://sildenafil.llc/#]Cheap Viagra 100mg[/url] cheap viagra

cialis great price: cialis without a doctor prescription – cialis discounts

buy 5mg cialis online: Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription – purchase cialis with paypal

http://sildenafil.llc/# generic viagra without a doctor prescription

https://sildenafil.llc/# viagra without a doctor prescription

viagra cialis melbourne site:au [url=https://tadalafil.auction/#]Buy Tadalafil 20mg[/url] cialis online with no prescription

http://sildenafil.llc/# ed pills that work better than viagra

cost of viagra: Cheap Viagra 100mg – buy generic viagra online

viagra without a doctor prescription: Cheap Viagra 100mg – viagra

https://tadalafil.auction/# cialis super active 20 mg

generic viagra 100mg [url=https://sildenafil.llc/#]buy sildenafil online canada[/url] generic viagra

http://tadalafil.auction/# brand cialis

best place to buy cialis online forum: Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription – cialis samples online

how long does viagra last: Cheap generic Viagra – viagra prices

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

ed pills

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican drugstore online

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacies safe

cheapest ed pills

medication from mexico pharmacy: Mexico pharmacy online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacy paypal

erectile dysfunction meds online

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# indianpharmacy com

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacy

what is the cheapest ed medication

mexican drugstore online: Best pharmacy in Mexico – medicine in mexico pharmacies

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican rx online

where can i buy ed pills

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacies safe

buy ed pills online: Cheap ED pills online – online ed pills

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican mail order pharmacies

erectile dysfunction pills online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# best ed medication online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# cheap ed medication

ed online pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: best online pharmacies in mexico – best online pharmacies in mexico

india pharmacy: Online pharmacy – indian pharmacy online

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

indian pharmacy online: Indian pharmacy online – Online medicine home delivery

top 10 online pharmacy in india: top online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy online

https://edpillpharmacy.store/# cheap erection pills

ed meds online: Best ED meds online – pills for erectile dysfunction online

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# best india pharmacy

indianpharmacy com: best online pharmacy india – indian pharmacies safe

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: Medicines Mexico – medicine in mexico pharmacies

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# best online pharmacies in mexico

get ed meds online: ed pills online – cheap ed medication

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# pharmacy website india

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico pharmacy win – mexican mail order pharmacies

best ed medication online: Cheap ED pills online – cheapest ed treatment

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# indian pharmacies safe

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: Best pharmacy in Mexico – best online pharmacies in mexico

best online pharmacies in mexico: Certified Mexican pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# mail order pharmacy india

online ed meds: ED meds online with insurance – where to buy ed pills

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexico pharmacy win – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://indiapharmacy.shop/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://edpillpharmacy.store/# online erectile dysfunction prescription

top 10 online pharmacy in india: Online pharmacy – india pharmacy mail order

indian pharmacy: Best Indian pharmacy – indian pharmacy online

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# world pharmacy india

how to get ed pills: Best ED pills non prescription – ed doctor online

order ed meds online: ED meds online with insurance – erectile dysfunction online prescription

http://indiapharmacy.shop/# mail order pharmacy india

buying prescription drugs in mexico: Certified Mexican pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican mail order pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican drugstore online

cheap ed pills online: Cheapest online ED treatment – buy ed pills

online erectile dysfunction prescription: online ed prescription same-day – pills for ed online

https://mexicopharmacy.win/# mexican rx online

indian pharmacy online: Top online pharmacy in India – indianpharmacy com

online ed pharmacy: ed medicines – erectile dysfunction medicine online

indian pharmacies safe: Cheapest online pharmacy – top 10 online pharmacy in india

erectile dysfunction medications online: buy ed medication online – online ed medication

Дэдпул и Росомаха смотреть https://bit.ly/deadpool-wolverine-trailer-2024

buying prescription drugs in mexico: mexican pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: Certified Mexican pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

top 10 pharmacies in india: Top mail order pharmacies – india pharmacy mail order

ed medication online: Cheap ED pills online – cheap boner pills

reputable indian pharmacies: Online pharmacy USA – pharmacy website india

where can i buy erectile dysfunction pills: ED meds online with insurance – ed treatments online

Cytotec 200mcg price [url=http://cytotec.pro/#]cheapest cytotec[/url] buy cytotec pills

buy cytotec online http://lipitor.guru/# lipitor

lasix pills

https://lipitor.guru/# buy lipitor cheap

furosemide 40 mg: buy furosemide – lasix furosemide 40 mg

tamoxifen breast cancer prevention: buy tamoxifen online – tamoxifen therapy

Abortion pills online [url=https://cytotec.pro/#]Misoprostol price in pharmacy[/url] Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

cytotec buy online usa http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 125 mg

lasix online

п»їcytotec pills online https://lisinopril.guru/# buy zestril 20 mg online

lasix dosage

compare zestril prices: Lisinopril refill online – lisinopril australia

cytotec pills buy online: Abortion pills online – buy cytotec over the counter

https://lipitor.guru/# cost of lipitor

buy cytotec online [url=https://cytotec.pro/#]cytotec best price[/url] order cytotec online

cytotec online http://furosemide.win/# lasix furosemide

furosemide 40 mg

https://lipitor.guru/# lipitor generics

buy cytotec pills https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 20mg india

buy lasix online

tamoxifen adverse effects: buy tamoxifen citrate – tamoxifen buy

tamoxifen cost [url=http://tamoxifen.bid/#]tamoxifen hot flashes[/url] tamoxifen adverse effects

purchase cytotec https://furosemide.win/# lasix side effects

lasix uses

https://lipitor.guru/# buy generic lipitor canada

buy misoprostol over the counter https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen medication

lasix

https://lisinopril.guru/# zestoretic coupon

tamoxifen medication [url=http://tamoxifen.bid/#]tamoxifen hip pain[/url] does tamoxifen make you tired

buy cytotec online https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec

lasix furosemide

https://lipitor.guru/# lipitor brand name price

tamoxifen cyp2d6: Purchase Nolvadex Online – tamoxifen cancer

buy cytotec pills http://cytotec.pro/# buy misoprostol over the counter

lasix uses

https://lisinopril.guru/# can i buy generic lisinopril online

tamoxifen citrate pct [url=https://tamoxifen.bid/#]tamoxifen dosage[/url] tamoxifen premenopausal

buy cytotec in usa: cheapest cytotec – cytotec abortion pill

lisinopril 10 mg best price: Lisinopril refill online – lisinopril 20 mg purchase

buy cytotec online https://tamoxifen.bid/# tamoxifen headache

lasix dosage

https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec pills

buy cytotec online fast delivery https://lipitor.guru/# lipitor 40

lasix tablet

cytotec buy online usa: cytotec best price – cytotec online

buy cytotec pills: cytotec abortion pill – buy cytotec in usa

http://lipitor.guru/# lipitor 80 mg price in india

best price for generic lipitor: Atorvastatin 20 mg buy online – lipitor generic india

buy misoprostol over the counter: buy cytotec online fast delivery – buy cytotec in usa

Cytotec 200mcg price https://furosemide.win/# lasix medication

lasix online

http://tamoxifen.bid/# nolvadex 10mg

buy cytotec online http://tamoxifen.bid/# nolvadex estrogen blocker

lasix for sale

http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 40 mg pill

purchase cytotec: cheapest cytotec – п»їcytotec pills online

lisinopril generic price: Lisinopril refill online – lisinopril 5 mg for sale

cost for 40 mg lisinopril: 60 mg lisinopril – lisinopril 20mg india

buy misoprostol over the counter https://lipitor.guru/# average cost of generic lipitor

lasix for sale

furosemida: lasix generic name – lasix dosage

buy cytotec in usa https://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril 422

furosemide 100 mg

lasix for sale: cheap lasix – lasix dosage

buy cheap lipitor online: lipitor 10mg generic – lipitor generic brand name

buy cytotec pills: buy misoprostol tablet – cytotec pills buy online

buy misoprostol over the counter https://lipitor.guru/# cost of lipitor 20 mg

lasix dosage

20 mg lisinopril tablets: cheap lisinopril – lisinopril buy online

cytotec abortion pill https://cytotec.pro/# buy cytotec in usa

furosemide 100 mg

femara vs tamoxifen: Purchase Nolvadex Online – tamoxifen skin changes

cytotec pills buy online http://lisinopril.guru/# lisinopril drug

buy furosemide online

lasix online: buy furosemide – furosemida

buy cytotec online: buy cytotec online – cytotec buy online usa

cytotec abortion pill https://cytotec.pro/# Cytotec 200mcg price

furosemida 40 mg

buy lasix online: furosemide online – furosemide 40 mg

buy cytotec pills: Misoprostol price in pharmacy – Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

indian pharmacy online [url=http://easyrxindia.com/#]indian pharmacy paypal[/url] top online pharmacy india

https://mexstarpharma.online/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian online pharmacy

https://easyrxindia.com/# indianpharmacy com

indian pharmacy [url=https://easyrxindia.shop/#]online shopping pharmacy india[/url] online pharmacy india

https://easyrxcanada.online/# reputable canadian pharmacy

https://easyrxcanada.online/# canadian pharmacy drugs online

the canadian pharmacy [url=https://easyrxcanada.online/#]canadapharmacyonline[/url] reliable canadian pharmacy reviews

online pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – india pharmacy mail order

https://easyrxindia.com/# best online pharmacy india

https://easyrxindia.com/# india online pharmacy

buying prescription drugs in mexico online [url=https://mexstarpharma.com/#]best online pharmacies in mexico[/url] medication from mexico pharmacy

recommended canadian pharmacies: canadian pharmacy mall – the canadian drugstore

http://mexstarpharma.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexstarpharma.com/#]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies

online shopping pharmacy india: indian pharmacies safe – india pharmacy mail order

https://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian pharmacy meds

https://mexstarpharma.online/# reputable mexican pharmacies online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: mexican drugstore online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs [url=https://mexstarpharma.com/#]mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] mexican drugstore online

safe online pharmacies in canada: ordering drugs from canada – legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy

https://easyrxindia.shop/# india online pharmacy

canadian pharmacy mall: best canadian online pharmacy – canadian king pharmacy

https://mexstarpharma.com/# medicine in mexico pharmacies

indian pharmacy online: buy medicines online in india – indianpharmacy com

http://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian drug

india pharmacy: pharmacy website india – Online medicine order

http://mexstarpharma.com/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://easyrxcanada.com/# canadian world pharmacy

Online medicine order: reputable indian pharmacies – buy prescription drugs from india

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

reputable mexican pharmacies online: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://easyrxindia.shop/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadian king pharmacy: canadian pharmacy ratings – canadian drugs pharmacy

casino slot siteleri: yasal slot siteleri – casino slot siteleri

deneme bonusu veren siteler: deneme bonusu – deneme bonusu veren siteler

However, since there were fewer ovulated follicles, this experiment suggests that follicles were lost from the ovulatory pool can you buy priligy in the u.s.

deneme bonusu veren siteler: bonus veren slot siteleri – slot casino siteleri

deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri: slot siteleri – slot oyun siteleri

slot siteleri bonus veren: slot bahis siteleri – slot siteleri bonus veren

http://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# bonus veren siteler

sweet bonanza slot: sweet bonanza free spin demo – sweet bonanza slot

en yeni slot siteleri: canl? slot siteleri – slot siteleri bonus veren

deneme bonusu veren siteler: deneme bonusu veren siteler – deneme veren slot siteleri

sweet bonanza taktik: sweet bonanza yasal site – sweet bonanza taktik

deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri: slot oyunlar? siteleri – slot casino siteleri

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# bahis siteleri

http://sweetbonanza.network/# slot oyunlari

slot casino siteleri: slot oyun siteleri – slot siteleri guvenilir

http://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu

slot oyunlar? siteleri: bonus veren slot siteleri – guvenilir slot siteleri

http://sweetbonanza.network/# sweet bonanza 90 tl

slot casino siteleri: slot kumar siteleri – bonus veren casino slot siteleri

slot casino siteleri: slot bahis siteleri – guvenilir slot siteleri 2024

slot oyunlar? siteleri: en guvenilir slot siteleri – deneme bonusu veren siteler

https://sweetbonanza.network/# guncel sweet bonanza

bonus veren slot siteleri: slot casino siteleri – deneme bonusu veren slot siteleri

https://denemebonusuverensiteler.win/# deneme bonusu veren siteler

пин ап вход: pin up – пин ап зеркало

1вин: ван вин – 1win официальный сайт

Расстановки по Хеллингеру, все о методе семейных расстановок. https://rasstanovkiural.ru

https://pin-up.diy/# pin up казино

пинап казино: пин ап казино вход – пинап казино

http://vavada.auction/# vavada казино

казино вавада: вавада рабочее зеркало – вавада зеркало

pin up casino: пинап казино – пин ап

1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия: 1хбет зеркало – 1хбет

1xbet [url=http://1xbet.contact/#]зеркало 1хбет[/url] зеркало 1хбет

https://pin-up.diy/# пин ап вход

vavada казино: вавада – vavada казино

pin up казино: pin up – pin up casino

пинап казино: пинап казино – pin up casino

https://vavada.auction/# вавада зеркало

пин ап вход: пин ап – пин ап вход

пин ап зеркало: pin up casino – пинап казино

https://vavada.auction/# вавада рабочее зеркало

1xbet зеркало: 1хбет официальный сайт – 1xbet скачать

https://pin-up.diy/# пин ап вход

1xbet: 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня – зеркало 1хбет

зеркало 1хбет: 1хбет официальный сайт – 1xbet официальный сайт

https://vavada.auction/# vavada

1хбет: 1xbet зеркало рабочее на сегодня – 1xbet официальный сайт мобильная версия

http://1win.directory/# 1вин официальный сайт

вавада рабочее зеркало: vavada – vavada

https://drstore24.com/# allegra pharmacy prices

depakote pharmacy

https://easydrugrx.com/# colchicine pharmacy

Ventolin [url=https://onlineph24.com/#]periactin online pharmacy no prescription[/url] pharmacy home delivery

bystolic pharmacy discount card: sams club pharmacy levitra – xlpharmacy review viagra

https://onlineph24.com/# eu pharmacy online

lexapro online pharmacy no prescription

best drug store primer: retail pharmacy price cialis – doc morris pharmacy artane

https://easydrugrx.com/# duloxetine online pharmacy

Claritin

best online pharmacy percocet: can i buy viagra from tesco pharmacy – drug store

https://onlineph24.com/# seroquel xr online pharmacy

viagra in pharmacy malaysia

https://easydrugrx.com/# clomid online pharmacy uk

vipps online pharmacy viagra

pharmacy today: medi rx pharmacy – domperidone online pharmacy

https://onlineph24.com/# spain pharmacy viagra

Malegra FXT [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]cheapest order pharmacy viagra[/url] online overseas pharmacy

https://drstore24.com/# Aebgstymn

unicare pharmacy dublin artane castle [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]priceline pharmacy viagra[/url] va online pharmacy

https://onlineph24.com/# prozac pharmacy prices

humana pharmacy rx

tesco pharmacy fluconazole: Viagra capsules – online pharmacy reviews cialis

https://drstore24.com/# online pharmacy rx

pharmacy online shopping

https://drstore24.com/# wal mart pharmacy prices cialis

best online propecia pharmacy [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]warfarin pharmacy protocol[/url] cymbalta online pharmacy

Super P-Force: celebrex online pharmacy – proscar uk pharmacy

trusty pharmacy acheter xenical france: subutex online pharmacy – nabp pharmacy

https://drstore24.com/# online pharmacy ambien overnight

24 hours pharmacy store [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]pharmacy online track order[/url] bactrim pharmacy

Macrobid: rx partners pharmacy – people’s pharmacy generic wellbutrin

Зайдите на официальный сайт https://888starz.today и получите все преимущества

https://drstore24.com/# online pharmacy to buy viagra

provigil india pharmacy [url=https://drstore24.com/#]online viagra pharmacy[/url] ed pharmacy cialis

cheap cialis online pharmacy: provigil mexican pharmacy – online pharmacy tegretol xr

https://drstore24.com/# methotrexate audit pharmacy

online pharmacy brand viagra [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]buy clomid online pharmacy[/url] Maxolon

online pharmacy no prescription ventolin: compounding pharmacy prometrium – mobic online pharmacy

fred meyer pharmacy hours: tetracycline pharmacy – pharmacy escrow viagra

discount online pharmacy viagra: austria pharmacy online – online pharmacy finpecia

https://pharm24on.com/# pharmacy direct cialis

inducible clindamycin resistance in staphylococcus aureus isolated from nursing and pharmacy students [url=https://onlineph24.com/#]pro cialis pharmacy[/url] anti-depressants

https://easydrugrx.com/# platinum rx pharmacy

periactin online pharmacy no prescription [url=https://easydrugrx.com/#]dilaudid online pharmacy[/url] legit mexican pharmacy

mebendazole online pharmacy: avodart online pharmacy – generic pharmacy propecia

internet pharmacy mexico: Prevacid – roadrunner pharmacy

military pharmacy viagra: world pharmacy store reviews – online pharmacy adipex

https://drstore24.com/# singulair mexican pharmacy

cialis online uk pharmacy [url=https://pharm24on.com/#]pharmacy viagra prices[/url] study pharmacy online free

discount pharmacy online: zetia coupon pharmacy – online pharmacy reviews propecia

Comments are closed.